In the elegant lobby of Eaton DC, the new four-star hotel and co-working members club for artists and community change-makers on K Street, colorful C-notes have begun to paper one wall. Mounting in a rising grid, these Fundred Dollar bills feature new portraits—an exuberant superhero, a charcoal image of Martin Luther King, a fluorescent map of the earth. In the central oval where Ben Franklin’s face is expected, a turquoise Twitter bird on one and a graphic bat are inserted in the place of the Great Seal of the United States. Each drawing, created on site, brims with energy and individual expression. On this fabled avenue of power and money in politics near the White House, these hundred dollar bills take on a new collective significance. This is amplified, in the center of the lobby, by the Fundred Presentation Pallet (Reserve), the bills created over the past decade by half a million participants in Mel Chin’s ongoing Fundred Dollar Bill Project, a community-based collaborative artwork that joins individual voices in proclaiming the value of individual human lives and calling for action to solve the crisis in lead poisoning.

“The project isn’t about me,” Mel Chin insists repeatedly on a visit to Washington, DC. While he initiated the project, everyone creating a Fundred becomes an artist and co-author. The initiative started as Operation Paydirt in post-Katrina New Orleans, where the original interpretations of $100 bills were first drawn by hand and collectively displayed. It grew into an educational campaign directed by Amanda Wiles that has involved over a thousand schools, departments of health, and nonprofits across the country.

For more than 35 years, Chin has created art that tackles difficult problems in a manner that joins together disparate realities. Born in Houston to Chinese American parents, he draws on multiple cultural realities and mythologies, defies categorization, and has no signature style. What is signature throughout his work is a theme of transformation and a dedication to solving problems through investigating how things work and what things mean.

Chin began as a sculptor who prized what the hand could do, and is increasingly acknowledged as a pioneer of a kind of participatory public art able to engage people from every background and walk of life. Chin’s is an art of catalyzing awareness, of waking up and seeing what was there all the time but was not noticed. While some conceive of conceptual art as indifferent to the object, his commitment to making things with devoted attention is a form of alchemy, of transformation.

Picked up by the Fundred Armored Truck in a journey of 21,000 miles, and powered along the way by used vegetable oil at school cafeterias, the bills were delivered to the nation’s capital to be exhibited collectively at Eaton DC through June 2019. Here the Fundreds were assembled into carefully tied bricks of equal size, as cash is in the nearby Federal Reserve Bank vault.

Elevated on a honey-colored wooden plinth, they constituted what was identified by a ten-foot-high stone plaque, behind a red velvet rope: “BY THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA/FUNDRED RESERVE.” Whether drawn by a child or by a visiting CEO, each bill was equally valued and only one per person was allowed—“like a vote,” Chin says. The installation included a space for drawing, the handcrafted cherry table of the Fundred Mint, and participants could also bring in bills based on a template on the project’s website. If the maker chose to donate a Fundred to the project, it was added to the wall display. In the tradition of much conceptual art where documentation supplants or traces materiality, each person who created a Fundred received back a “Certificate of Value Created.”

The Eaton brand—already open in Hong Kong and planned for San Francisco, Seattle, and Toronto—was uniquely poised to host the participatory exhibition. It has pledged to invest profits from the luxurious rooms to fund residencies for “marginalized and under-represented” artists and to support grassroots activism, says Founder and President Kat Lo. She is a member of the billionaire Langham Hotel family and a distinguished environmental activist who was a key organizer of the World Trade Organization protests in Hong Kong in 2005. The location is rife with contrasts to a surrealist degree. The identity of K Street has been defined by Washington’s lobbying industry, the well-paid traders of money for policies that will make their employers more money, rather than policies that effectively address the problems of constituents who may be poor and without access to such influence.

This project fit with the mission of Eaton House’s then Director of Culture, Sheldon Scott, himself a conceptual and performance artist. To celebrate Eaton’s opening in September 2018, he organized a panel on art as a conduit for social change, including AJ Schnack, Zoë Charlton (whose mosaic graces the rooftop space), Robin Bell, and John Deardourff. He refers to Chin as a “guiding light.”

Sitting in the carefully curated library at Eaton DC, Chin spoke of how lead poisoning locks into brain and bone, how there is no safe level of lead. He explained that when he visited New Orleans after Katrina he was stunned to discover that even prior to the storm, 30 to 50 percent of inner-city children had lead poisoning. While the project began in New Orleans and focused on funding for the lead problem there, nearly 3,000 US neighborhoods have since been reported by Reuters to have lead poisoning rates higher than those recorded at the 2015 height of the crisis in Flint, Michigan. Lead contamination is in soil, air, and water, the legacy of products that for decades contained it: paint, fuel, industrial waste, and lead pipes.

Using the tools of in-depth research, investigation, and collaboration with knowledge teams, Chin learned that this exposure is preventable and that strategic plans to solve the problem exist. In New Orleans alone it would take about $300 million to remedy the problem, but there was no comprehensive funding to address it. In 2006, he discovered an abandoned New Orleans house being used as an art center in the St. Roch neighborhood and learned that three children who had lived in that house had lead poisoning and were having trouble in school. He used his own funding to remediate the house’s lead problems and named it The Safehouse, securing it with a vault-like door that became part of the Eaton exhibition. The Fundred Project began here, on a plot of land healed in the way the project envisions for every property and house with lead contamination.

Displayed at Eaton DC, the Fundred Project coalesced into a finely crafted installation that effectively countered the invisibility of the nation’s lead crisis. Described by Chin as a representation of the voices of children as money (value), the drawings make tangible the extent and personal nature of the lead crisis. The project’s documentation declares, “As the Fundred Dollar Bill collection continues to grow, we want the Fundreds’ worth applied to eliminating lead poisoning. To make sure that happens, we are presenting these drawings to our nation’s leaders to support action to deal with this destructive element, once and for all.” Congressman Dan Kildee, whose district includes Flint, Michigan, adds that “What [this exhibition] does, especially for those here in Washington who don’t have a connection to my hometown and places like Flint, is make it really clear that there is a very high cost to not protecting those kids.”

The project aims to “imagine, express, and actualize a future free of childhood lead poisoning.” Adjacent to the drawing space was a station providing further context: a video loop with documentation of legislative visits, photos of the history of the project, and animation addressing the lead crisis. As much as the Fundred Project aims to eliminate lead poisoning, it also works on an individual level, empowering participants and releasing energy through the act of drawing. Chin has stated that “making objects and marks is also about making possibilities, making choices—and that is one of the last freedoms we have.” He also stresses the importance of reasserting empathy into the public space and engaging elected leadership in taking responsibility for protecting their constituents.

The way the project has taken time and has adapted multiple strategies in its problem-solving mission is characteristic of many conceptual projects, defying the idea of an artwork as a single event. One expression that appears frequently on the Fundreds is the “e pluribus unum” (out of many, one) that appears on all United States currency. As traditional venues for art, such as galleries and museums, seek to engage more diverse audiences, overcome polarization, and reclaim art as a way of finding voice, the kind of participatory art led by Mel Chin can be experienced as a way of reclaiming democracy. As a New York sixth-grade participant declares in an on-site video, “We’ll send the bill and it will go to fix New Orleans and New Orleans will know we care. That’s important, because it’s a state of us.”

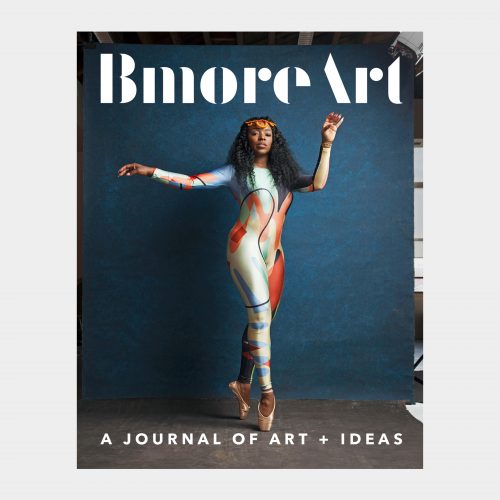

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Issue 07 of the BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas

Photos courtesy of Eaton DC and portrait of Mel Chin by Randall Scott