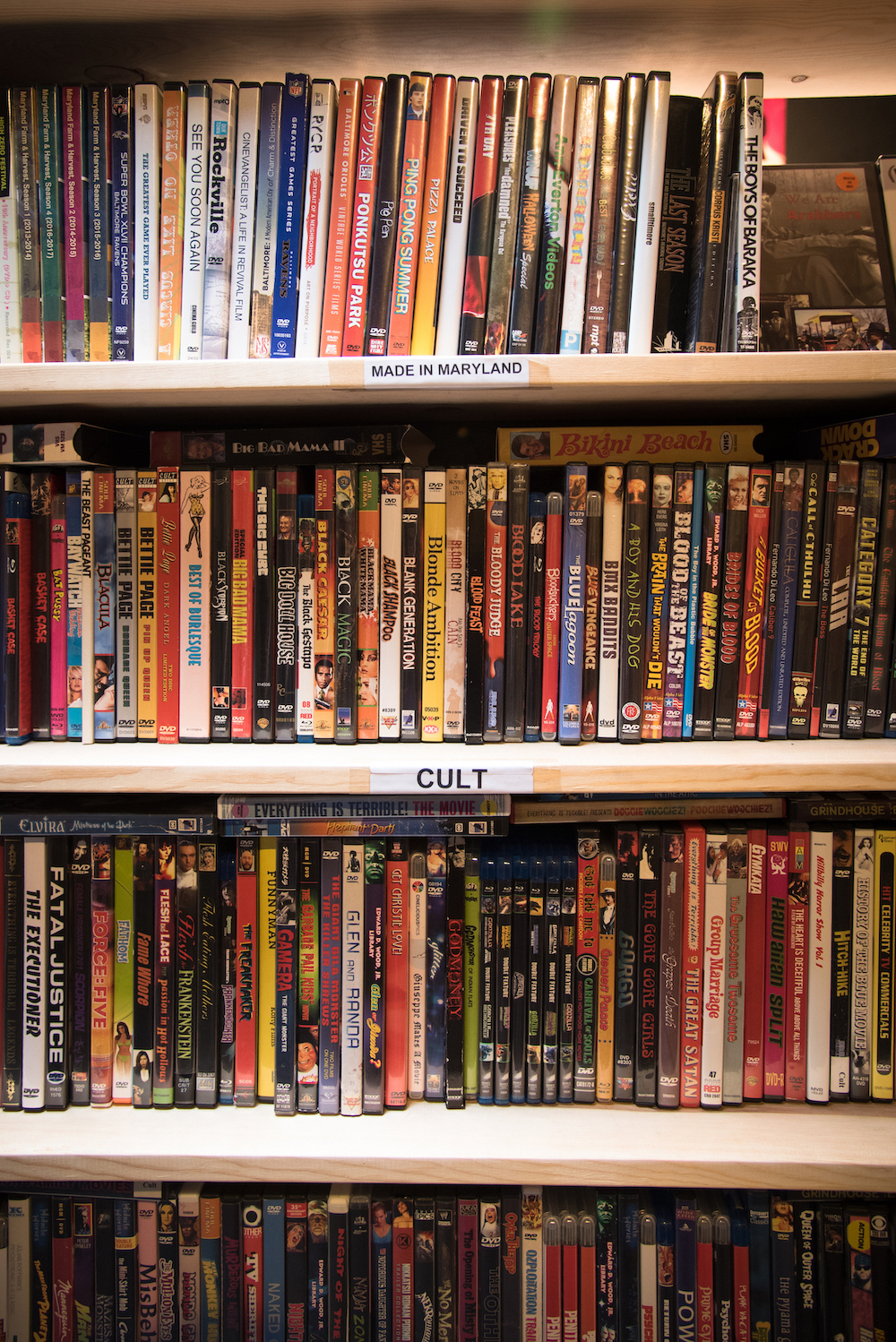

Inside Beyond Video, the rowhouse with the hypnotic paint job next to the Ottobar, there are thousands of Blu-Rays, DVDs, and even some VHS—a defiant, pro-stuff counterpunch to Amazon, Netflix, and other streaming sites that keep us inside, on our couches, and away from the rest of the world.

You can’t just walk in and rent at Beyond Video, you pay a monthly subscription: $12 a month to rent up to three titles at a time or $20 to rent up to six at a time; either way there’s unlimited rentals per month. And really, you’re paying for access to a singular collection and, just as importantly, supporting a Sisyphean idea: the collectively run, nonprofit store as an IRL answer to the cloud’s propaganda of immediate easy access.

“Algorithms make streaming movies a mostly homogenized and repetitive experience. Going into a physical video store is so completely different from scrolling through endless titles,” Beyond Video collective member Liz Donadio says. “There are people there who you can ask for advice, there is a curated and diverse collection, and you have the chance to find and see something influential.”

According to streaming prognosticators, all of movie history is out there on the internet. The reality is all of movie history has now spread across multiple online services, a rights transfer or movie studio sale away from disappearing temporarily, or forever. “People have a sense that because something is on Amazon or Netflix or, worst of all, something is on YouTube, that it has been properly archived, that it is eternally available, and that is not the case,” collective member Eric Hatch says. “Having physical objects cared for and kept in a collection and made available is better than relying on it being available at a link.”

For some perspective: Beyond Video has around 13,000 titles—twice as many as Netflix (which currently has around 6,000 titles for streaming), three times as many as Hulu (around 4,000), and close to approximating Amazon Prime’s online inventory (around 20,000, though it is an unnavigable, terribly-tagged mess). Beyond Video’s collection comes from donations, yard sales and thrift stores, and a purchasing budget derived from subscriber fee revenue.

For many Baltimoreans, a video store for serious filmgoers immediately evokes the movie-geek spirit of Video Americain, which closed its last store in 2015. The idea for Beyond Video began in 2013, when it was clear Video Americain was not long for this world. But Beyond Video offers more than nostalgia—it also offers access, explains filmmaker Meredith Moore, a former collective member who still volunteers at the store. Beyond Video provides many titles not available at all on the internet and that are prohibitively expensive to publicly screen—an experience curators such as Moore experience firsthand.

“Providing access to art and film is something that I believe is extremely important,” Moore says. “This is why libraries and nonprofit circulating collections like Beyond Video are so important. Access for all!”

Photos by Rachel Rock

More info at Beyond Video’s website.

This story was published in BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas Issue 08: Archive.