Okay so honestly, the best Baltimore movies of 2019 were that clip that went all around Twitter of that dude riding on the hood of a Baltimore Police car all like, “ayyyyyy,” and Zia Anger’s My First Film at the Parkway, but neither of those are movies at all. The former is a nine-second-long clip (viewed almost half-a-million times) of, as Stacia Brown wrote, “the absurdist counter-dimension housed within one of the oldest states in America.” And the latter, a performance piece rather than a movie, all about labor, parents/parenting, reproductive rights, rage, and a meta-commentary on so-called “juvenilia” and the male-run movie industry.

I start there because what they both share with the short films, music videos, web series, video collage, and few feature-length movies “proper” that are the best Baltimore movies of 2019 as far as I am concerned, is a sense of nonfiction gone ecstatic. Not documentary exactly (though a few fit that category) but works where reality sneaks up and disrupts form and storytelling in unpredictable and expressionistic ways.

Well Groomed

Well Groomed

Rebecca Stern’s Well Groomed (produced by former Baltimorean Justin Levy, scored by Dan Deacon) looks at the weird world of creative grooming—dyeing one’s dog’s hair and shaving and styling it so one can turn a dog into say, a Buffalo or Pennywise from It—and it is snark-less, opting for wizened sympathy and slightly surreal cinematics. Its visual imagination is as broad as its subjects, like Adriane Pope, creative grooming samurai who sees a dog’s hairy leg and imagines, um, Johnny Depp as the Mad Hatter sculpted into it?

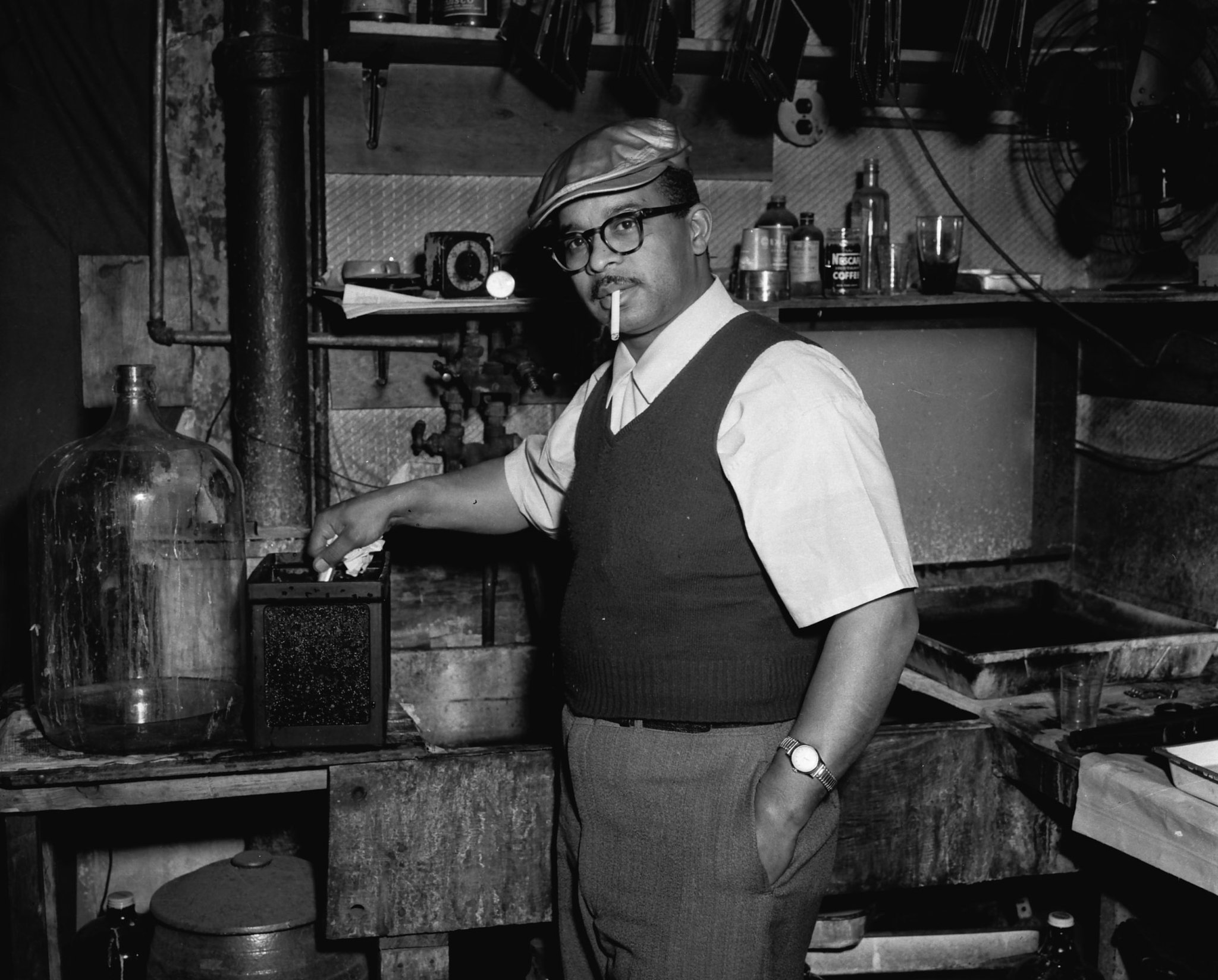

When TT The Artist began making Dark City: Beneath the Beat, a documentary about club music, there was something exciting and admirably Sisyphean about the task. The history of club music is complicated and full of infighting and frustration and getting anywhere with it means pissing off some of its key players. With music so influential and misunderstood (not to mention ripped off and exploited), even an honest and informed approach could end up fraught. But by the time Dark City: Beneath the Beat arrived, it was a Busby Berkeley-ing of club music: militants in red march (and rap and dance) at the harbor, a ballerina wanders the Oak Lawn Cemetery, a mustard yellow-drenched dance party traces club’s origins back to soul music’s rhythmic inclusivity. It is not so much a movie about club music as it a movie of club music.

Lost Kings, a three-part series hosted on YouTube, focuses on young dirt biker Max (played by noted dirt biker Wheelie Queen), reeling from the shooting of her brother Donte (played by another local dirt biker, AJ). So she plots revenge against those who killed her brother and in the process taps into a conspiracy involving drug dealing and dirty cops. A debate between Max and Donte—in which Donte, dead, in front of his own funeral, explains that retaliation is not the way—sits somewhere between season three of The Wire and Atlanta, relaxed, naturalistic, surreal, and obvious (in a good way). Lost Kings isn’t exactly teachable like a lot of the street movies it’s riffing on, though it is full of knowledge and real-life ties to Baltimore.

Jamie Fulla Grace

Jamie Fulla Grace

“I just want an outfit that I can wear without getting cat-called, without getting misgendered, without looking like a yuppie—I’m tired of it,” Black trans activist, artist, and writer Jamie Grace Alexander declares early in Emily Eaglin’s Jamie Fulla Grace, a brash and truthful mini-doc that combines music video, reality TV, and neo-realist techniques. That it is also a portrait of a sort of a Black Baltimore bohemianism so far removed from the New York porn that passes as humanist filmmaking on HBO or Netflix is a bonus.

In Marnie Ellen Hertzler’s staggering Hi I Need To Be Loved, a series of Baltimoreans read from spam emails Hertzler received, turning the stunted, confused, or poorly translated language we all get in our inboxes into soliloquy. And then the conceit evolves and we see a few of those folks in something resembling real life, at locations that could be as AI-generated as the emails (at the strip club, in an abandoned house cutting onions, on a dairy farm). Spam delivered with gravitas.

The video for Ami Dang’s “Love-liesse,” directed by Meredith Moore, combines computer graphics and footage Dang herself shot during a trip to India, so like the best music videos, it is a low-key adaptation of the music you’re hearing—here, the electronic and acoustic melange that make up Dang’s music. Also like the best music videos, it looks really cool. Moore’s work is both heady and rakish: An unadorned digital grid is both a void and, apparently, the start of all things; a painting of two tragic lovers levitates, unbothered by the rough waters below, a tenuous moment of comfort that also made me think of the wobbling flying toasters from that one screensaver from the early ‘90s.

The oblique video loops of Black Baltimore created by Lawrence Burney for the Eubie Blake Art Center are more than the sum of their parts, though those parts matter too—elements of an often ignored Baltimore far from retro/regressive “how bout dem O’s” talk and Billy Don Shaffer worship: a joyous supercut of Black Baltimoreans graduating; queer club icon Miss Tony’s “EA-EA” soundtracks a clip from David Simon’s The Corner of kids partying to Tony as stacked images of steamed crabs are collaged behind it; eerie footage from almost 100 years ago of Black boys (one dressed as a horse) in Pigtown watched by a white audience. So much time is spent bloviating about Baltimore and what it all means but Burney’s odd, intuitive, archival work gets to something much more ineffable, both inspiring and dispiriting.

Ami Dang’s “Love-liesse,” directed by Meredith Moore

The po-faced documentary bubble will burst—thanks, Netflix—and all the movies above are the future, but the documentary “proper” has led to a cinematic advocacy in Baltimore that is welcome. Plus all of these docs have a whole lot of fight in them. Deserted, about food deserts in Baltimore, focuses on Anthony Francis of Harlem Park, who has started an urban garden and plans to open up a farm-to-table restaurant and is both an advocate for his neighborhood and a vicious critic of Baltimore’s failings. But director Emily Stubb realizes that once you start discussing that you’re presenting a larger history of redlining and racism and weaves thoughts from elementary and middle schoolers about their diets, a tangent on trash pick-up in poor communities, and a quick walk through DMG Foods, offering up a chatty, warm sort of didacticism.

Tony Mendez’s By Any Means Necessary: Stories Of Survival, a documentary about squeegee culture in Baltimore, was shot quickly, over just a few days, with a handful of voices gathered to explain why they squeegee. The villains are who you don’t see much of: Baltimore’s bougie types who treat squeegee-ers like trash, the cops that harass them, and the politicians content to vilify them. The movie is immediate and empathetic, and seething with Third Cinema’s quiet rage. So much of what it has to say is embodied in its opening credits, where shots of squeegee-ers working hard, hustling, is set to Jimi Hendrix’s iconoclastic take on “The Star Spangled Banner.”

By Any Means Necessary: Stories of Survival

B. Monét’s Ballet After Dark, about the program of the same name that Tyde-Courtney Edwards created as dance therapy for fellow survivors, is an exercise in emotional extremes and frenzied contrast. When Edwards describes her own sexual assault, we see stark, claustrophobic images that recall film noir, all countered by expressive Dark City: Beneath The Beat-like bursts of color and movement—the frame itself seems to get more vertical when people dance—and revealing therapy sessions right there in the studio.

One could try and squeeze Albert Birney’s Tux and Fanny into this catch-all “nonfiction gone ecstatic” category I created here—and as a movie stitching together a series of Instagram animations, it is a documentary of its own creation. But really it’s such a revelation and movie of the year material (its only competition: The Souvenir and Uncut Gems) and one of the best of the decade, so it makes sense to keep it as a straggler. And I spent a whole column with Tux and Fanny earlier this year, so you can read that. Here’s some of what I said back in June: “Two very kyooooot homunculi—one pink, the other purple—sit on a beach and contemplate, in Russian, the infinite by way of the sand surrounding them. Millions and millions of grains rendered, like most of Baltimore-based director/writer/animator Albert Birney’s Tux and Fanny, as a big-pixel ’80s video game and rudimentarily animated, recalling the leisurely rhythms of a cut scene from, say, Adventures of Lolo,” I wrote. “Saddled with a devastating kind of stoicism—like Mr. Bill or the donkey in Au Hasard Balthazar—Tux and Fanny deliver a silly sort of insight (their dialogue is somewhere between a koan and a really solid, sweet tweet) via short vignettes, shifting between the regular and spectacular.”

Which brings me back to My First Film. For this movie experience—it is the most emotional Powerpoint presentation of all time—Anger sits among the audience, typing messages to the viewers, commenting on her never-released feature debut Always All Ways, Anne Marie (made between 2010-2012, rejected from every film festival she submitted it to) which we get to see in large, arguably unsuccessful chunks alongside commentary on it scrolling down the right side of the screen. Occasionally, Anger pauses the movie to open up a relevant file from her computer and play some related video, a dramatic monologue in, like, 48-point font that is confessional and critical. The tension between choosing to end something and other people ending something for you is never quite reconciled—because it can’t be—and there is something so intimate about seeing someone’s desktop up there on a giant screen, exposed, while the cruel and/or comforting glow of a laptop screen hits them, tucked in the corner of the theater, in the dark, typing away, telling us so much.

Lastly, let’s talk streaming. Despite its promises of easy access to “everything,” ultimately these services take power away from you, the viewer, and keep you on your couch instead of outside, where you could be helping to build scene. Fortunately, here in Baltimore, we have theaters like the Parkway and the Charles and the Senator, and we have Beyond Video, a physical space to rent movies and meet people and talk movies before you wander back home to watch them. The nonprofit, volunteer-run video rental store is an incredibly inspiring endeavor that is doing it right, retraining our brains, not so much giving us what we want but what we need, forcing us all to think about the responsibilities to a community that comes together through fairly solitary act of watching movies, mostly alone, in the dark. Via Beyond Video collective member Eric Hatch, here are the ten most-rented movies at Beyond Video in 2019: Mandy (Panos Cosmatos, 2018)

House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977), The Love Witch (Anna Biller, 2016), Sorry to Bother You (Boots Riley, 2018), First Reformed (Paul Schrader, 2018), BlackKklansman (Spike Lee, 2018), Lemon (Janicza Bravo, 2017), Kedi (Ceyda Torun, 2016), Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017), and Zama (Lucretia Martel, 2017).

Featured image: screenshot from Dark City: Beneath the Beat