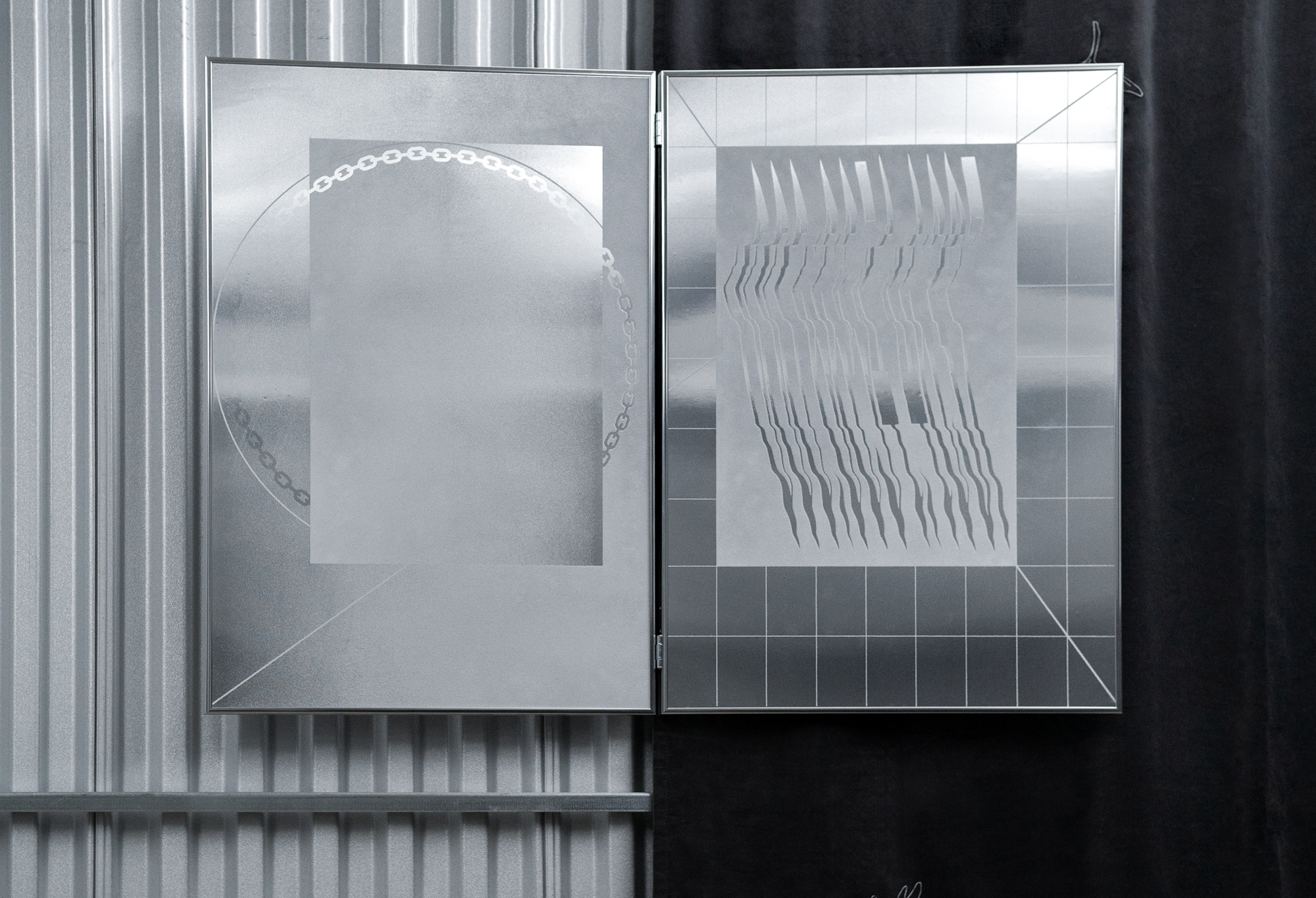

Getting to see James Bouché’s latest show is not easy. Located in a storage unit at Extra Space Storage in Remington, Family History Center requires that viewers request an appointment in advance then follow the artist along a snaking, fluorescent-lit hall flanked by identical white metal doors. It’s akin to entering a top-secret vault. Finally, Bouché arrives at unit #3209 and unlocks it to reveal a 10’ x 20’ room with seven silver-toned screen prints.

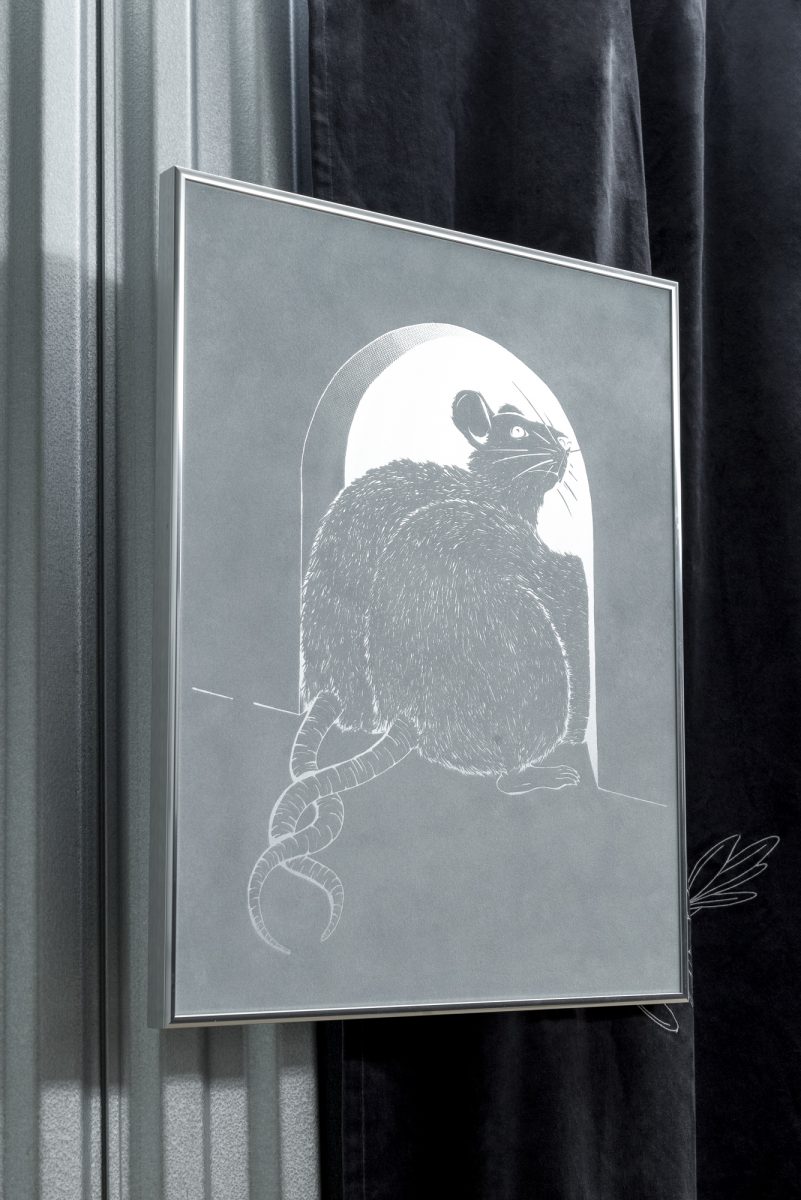

The compositions are clean and minimal: A chain circle intersected by a rectangle; two rodents with interlocking tails; two hands holding a rod inscribed with the words “Hold To Thy Rod” in Old English font. The scenes float in an otherworldly glow and the titles hint at an afterlife (“It’s Easy To Say ‘Forever’”; “Second Thoughts Before Eternity”). The room feels like some strange colorless limbo where a person might await judgment, but each print is velvet flocked on aluminum, allowing a certain softness in this cold and sterile surrounding.

Family History Center, on view through January 26, explores the Mormon practice of genealogical research and Bouché’s own experience being raised in the faith. The show’s unique location was in part inspired by Granite Mountain Records Vault, a storage facility in Utah that houses Mormon genealogical records and is managed by the Church of Latter-Day Saints.

This isn’t the first time Bouché has explored the subject matter—The Holy Ghost Goes to Bed at Midnight at School 33 touched on similar themes—but Family History Center feels like Bouché’s most explicitly personal show to-date, maybe because he is there to guide you through the material.

He prefaces the work by saying it’s specific to his own experience in the church and not critical of anyone’s faith or personal choices. “I do try to be objective in describing the practices that are part of the Mormon faith,” he says. “Shedding light on some of the shroud of mystery surrounding the church is enlightening to people and they can make up their own opinion.”

After 11 years in Baltimore, Bouché will move to New York next month with his partner, making this somewhat of a farewell show, although he promises an eventual return. (Full disclosure: Bouché and I are friends and former roommates). I chatted with him about Family History Center, the Mormon practice of baptisms for the dead—in which Mormons are baptized in the names of people who are deceased—and his decision to leave the faith at age 16.