As the largest global displacement crisis since World War II continues to unfold, two recently opened installations in Washington, DC museums offer provocative, distinct ways of thinking about migration and refuge. At the National Gallery of Art, Richard Mosse’s Incoming (2014–2017; curated by Sarah Greenough and Andrea Nelson, through March 22, 2020) is a forceful, ambitious work: Three massive screens display episodes filmed along two major immigration routes into Europe using a heat-sensitive surveillance camera. Meanwhile, the third floor of the Hirshhorn is largely filled with works by the protean modernist Marcel Duchamp (organized by Evelyn Hankins; through October 15, 2020)—whose influential practice is now often seen in terms of a spirit of exile and expatriation. Two very different shows, then, but in their divergent visions and scales, they combine to offer a compelling reminder of the complexity of international traffic, and of the potential meaningfulness of modest, individual gestures.

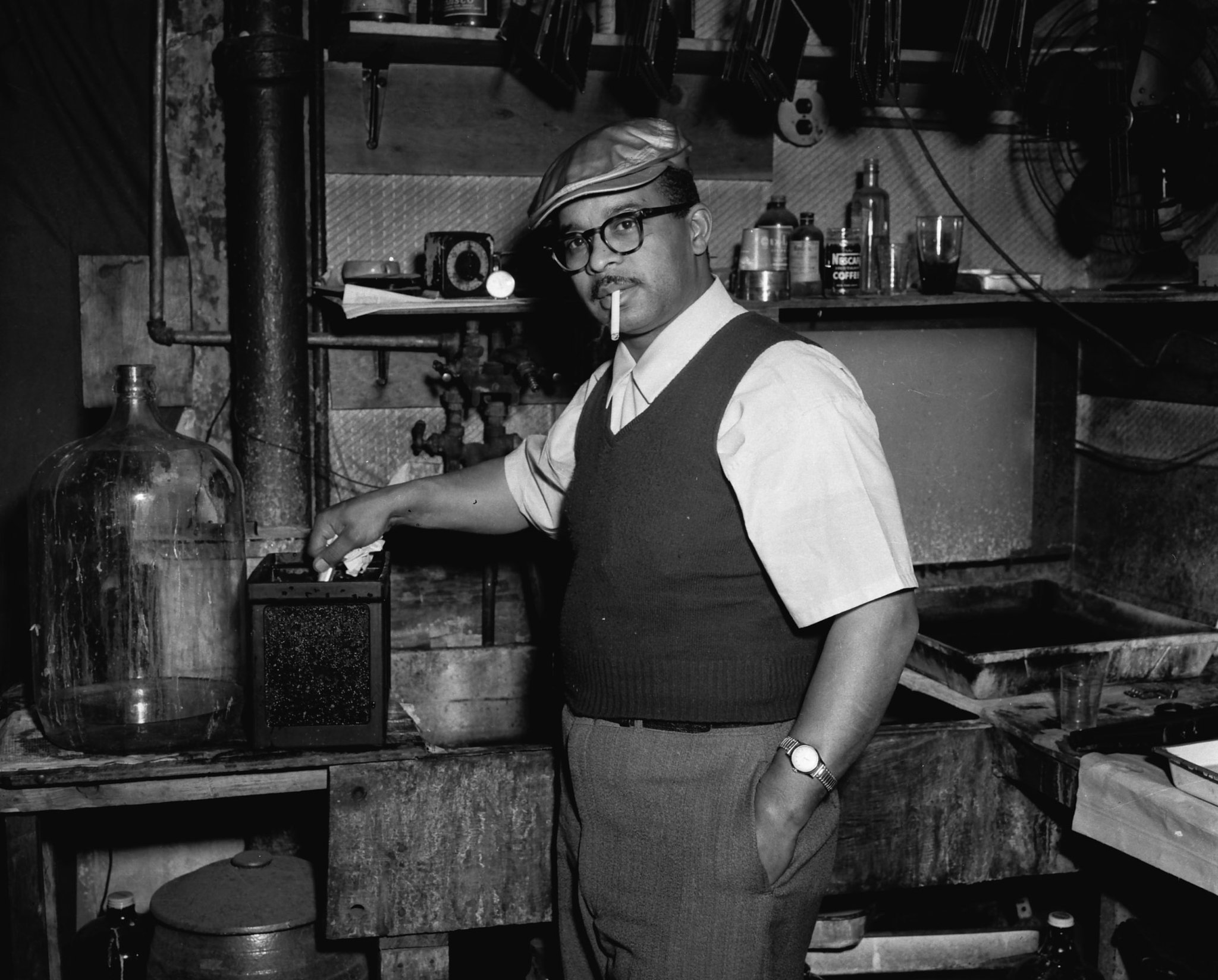

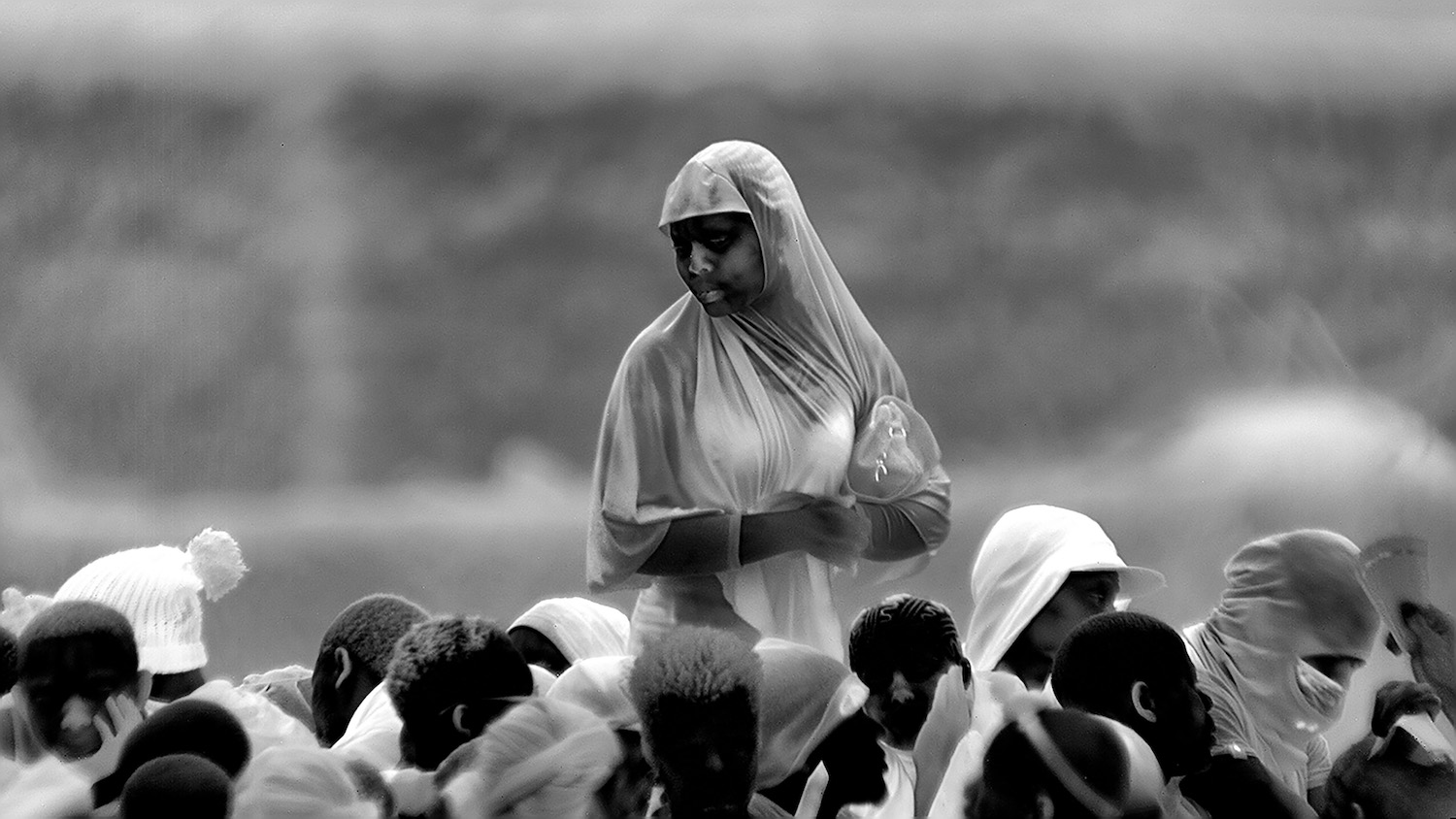

See Mosse’s work first—and give yourself some time. Directed by Mosse and shot by the cinematographer Trevor Tweeten, it’s a full 52 minutes long, and is intentionally challenging and unsettling. Using a highly sensitive thermal infrared camera originally designed for military use, the filmmakers recorded a range of scenes related to mass migration (a rescue at sea, a conversation between refugees, an autopsy, and so on). The images are in black and white, but the values are determined by the relative heat of the subjects—resulting in a spectral and icy look that conveys actions while also frustrating easy recognizability. That’s a critical point, for Mosse’s project seems largely motivated by the idea of reimagining a tool of surveillance. Instead of merely locating and exposing fugitives, that is, might it also reveal something about their plight and their humanity?

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #29, 2014–2017, digital chromogenic print on metallic paper. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist andJack Shainman Gallery, New York

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #29, 2014–2017, digital chromogenic print on metallic paper. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist andJack Shainman Gallery, New York

The answer turns out to be a qualified yes. Certainly, Incoming conveys the intimidating and coldly institutional aspect of the state machinery deployed in response to the influx of refugees in countries such as Turkey and Italy. In a landscape of sprawling harbors, enormous vessels, and hulking machines, medical workers in hazmat suits aid emigrants. Meanwhile, an industrial score by Ben Frost combines whining engines, hissing static, and jumbled voices—all originally recorded as ambient sound—in a montage that heightens the general mood of sublime danger and stress. And yet, even in this alien realm life still takes place, and Mosse seeks out instances of momentary calm and absorption. We see two refugees practice circus acrobatics; another tucks a photograph beneath a blanket in a temporary shelter, and a third kneels and prays on a sprawling tarmac. Importantly, too, the film is projected in slow motion, granting each motion and fleeting expression a heightened significance. One result is a sense of touching dignity, of people working to create meaning in a formidable environment.

But this is also ultimately a project centrally interested in its own medium. At certain points, Tweeten points the camera at the sun, the moon, and the ocean—apparently just to see what will happen. A sustained shot of jet fumes seems to have been included in large part because of the dots that result from the almost unimaginable heat: here, the medium simply gives way. And throughout, Mosse toys with various combinations of screens—now one; now two—and sound. To be sure, the results of this interrogation are occasionally powerful, as when the camera focuses on the invisible patches of heat momentarily left on a blanket by the hands of rescue workers attempting to warm a body plucked from the sea. The camera, here, is less a tool of surveillance than a delicate instrument that can reveal fugitive traces of sociability. Subsequently, however, we realize that Mosse seems just as interested in the visual beauty of such an image as in anything that it implies about people. In an accompanying video, he declares his interest in turning the camera towards aesthetic ends, and adds that beauty offers, in his view, “the sharpest tool in the box.” That would explain, I guess, a lengthy shot of billowing heat blankets, which seem more closely related to the sustained shot of a drifting plastic bag in American Beauty than to the plight of displaced refugees.

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #100, 2014–2017, digital chromogenic print on metallic paper. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist andJack Shainman Gallery, New York

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #100, 2014–2017, digital chromogenic print on metallic paper. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist andJack Shainman Gallery, New York

And it’s there, in my view, that Mosse’s work runs into real difficulties. Is this an attempt to earnestly grapple with a global crisis? Or is it a meditation on a curious medium? It seems to want to be both—but in trying to do so, it inevitably does a disservice to its human subjects. Or, better, its objects, for the actual refuges in Incoming are simultaneously othered and muted. Mosse has claimed that his use of thermal technology preserves their anonymity: perhaps, but in refusing to allow them to speak, he also denies them a basic agency. Even the title of the work, in this sense, feels awkward, as it suggests an analogy between displaced people and a threatening round of artillery. Obviously, a work of art need not aim at literalness, or simple documentary values. But as Candice Breitz, Francis Alÿs, and others have shown, mass migration can be addressed in ways that are at once oblique and humanizing. In Incoming, the human dimension is too often obscured by technical experimentation.

Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Which is why it’s worth then walking over to the Hirshhorn, to see the work of Duchamp—whose work consistently retained, over a lifetime of migration and dislocation, a notably personal aspect. Admittedly, Duchamp was a privileged traveler: He was able to finance his flight from France during World War I by selling several paintings, and he could afford to flee again two decades later, during the Nazi occupation. But his travels were not simply prompted by violence; rather, there was apparently something fundamentally migratory about Duchamp. A “poor little floating atom,” Ettie Stettheimer once called him, and indeed he had little interest in maintaining private attachments or taking on obligations. His work, in turn, reflected these tendencies. As T.J. Demos pointed out in a thoughtful 2007 book, Duchamp tended towards “an art of mobile objects and disjunctive spaces.”

That tendency is certainly visible in this show, which was motivated by a promised gift from the notable collectors Barbara and Aaron Levine. Laid out, for the most part, in chronological order, nearly all of the works on display come from their collection—and yet, strikingly, the museum offers almost no account of the Levines, or their interest in Duchamp. (A June New York Times feature is more helpful in this regard). Instead, the focus is on the artist, and nearly all of his most celebrated works—Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2; Fountain; The Large Glass, each fundamental to any history of modern art—are there. Or, at least, almost there. For in fact the Levine collection is built largely out of later reproductions, produced in series in the 1960s by a Duchamp intent on consolidating his legacy.

That may sound odd, and indeed it is initially disappointing to realize how little, in this show, dates to Duchamp’s early decades. Thus, we see one of 35 prints of L.H.O.O.Q. made in 1964 (45 years after Duchamp originally added a mustache to the Mona Lisa), several samples from a 1965 re-edition of his rotoreliefs (originally produced in 1935), and a 1975 print of a photograph of dust breeding (that was taken in 1920). If you’re after original, auratic objects by Duchamp, you still need to head to Philadelphia. That said, any initial dismay quickly yields to the realization that, in the case of Duchamp, there’s something particularly salient about reproductive technologies. After all, he was an artist centrally interested, as Calvin Tomkins once noted, in negation: in challenging longstanding notions about visual pleasure, authorship, and tradition. In frustrating our native desire for originals, this show is arguably true to his spirit.

Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Moreover, the preponderance of copies and serial editions also creates a sort of conceptual distance that is woven through the entire show. This is most evident in the beguiling Boîte-en-valise, which is one of a number of suitcases produced by Duchamp to hold, transport, and display small reproductions of 69 of his own works. As Demos has argued, it is a sort of portable museum, which combines nostalgia and a freedom from institutionalization: Here, the artist can assemble and show his entire scattered oeuvre on his own terms. (Or, as the collector Walter Arensberg once remarked to Duchamp: “You have invented a new kind of autobiography… You have become the puppeteer of your past.”) The project thus offers a pragmatic response to a central dilemma: how to retain, in a peripatetic existence, a sense of one’s past and one’s individuality? But in its reliance upon miniature reproductions, it also candidly acknowledges the basic fact of exile, recalling but not quite mirroring an original that exists elsewhere.

And once we realize that, the entire show seems to snap into focus, as a sort of rumination on distance. Especially in his later years, Duchamp consistently emphasized the active, participatory role of viewers in fashioning meaning. Unsurprisingly, several of his works were thus designed to be handled—like Please Touch, a cheeky magazine cover made from a hand-painted foam rubber breast, or Why not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy?, in which a birdcage holds a number of marble blocks carved to look like sugar cubes, confusing anyone who lifts the object (as a curious Robert Rauschenberg once did). At the Hirshhorn, however, we can’t interact with these pieces, as they’re protected by glass. We’re distanced from them: alert to their invitations, perhaps, but separated by a basic chasm. Or, to put it slightly differently, we are symbolic exiles, aware of a pull and an urge that we cannot ever satisfy.

Duchamp’s tombstone, in Rouen, carries an enigmatic epigraph: D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent (Anyway, it’s always the others who die). Oblique, irreverent, and slyly ironic (for, after all, the speaker lies beneath the earth), it’s typical of the artist. But it also points to a fundamental difference between Duchamp and Mosse. Mosse’s work is well-intended and earnest, but largely bereft of irony. Convinced of its own morality, it largely relies upon scale and an almost melodramatic use of slow motion to make its point. And yet, the artist’s evident fascination with surveillance technologies and abstract form marginalize the purported subjects of his work, reducing them to anonymous objects of our gaze. In short, we can see the plight of the displaced, but not feel it, or quite grasp it. By contrast, as we view Duchamp’s work, we begin to sense—in the reliance upon copies, in the humble dimensions of the work, in the fact that we can’t touch what we wish we could—the alienation of the exile. It’s a faint connection, sure, and Duchamp never actively solicits our sympathy. And yet that moment of affiliation is affecting.

Of course it’s not always the others who die. And of course we are all, as a postcard issued in conjunction with Incoming piously tells us, potential refugees. But while we live, and enjoy the chance to visit museums, both the fading heat of a handprint on a blanket and a suitcase filled with delicate miniatures can at least remind us of what we have to lose.

Top Image: Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #280, 2014–2017, digital chromogenic print on metallic paper. © Richard Mosse. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Richard Mosse: Incoming is on view at the National Gallery of Art through March 22, 2020, East Building, Concourse Level.

Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection is on view through November 9 2019 to October 12 2020 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.