Webster Phillips was around 9 years old when he first went out on assignment for the Baltimore Sun. Irving Phillips, his father, a staff photographer, brought Webster along with an extra camera so he could act as second photographer, getting detail shots while Irving focused on the action.

He was learning the family trade. Webster’s grandfather, I. Henry Phillips, was a photographer at the Afro-American newspaper. His father, Irving, also worked for the Afro, and traveled around the South with Martin Luther King Jr., documenting his speeches for the paper. In 1969, after he returned from serving in Vietnam, Irving was the first Black photographer hired by the Sun. Even Webster’s grandmother, Laura Phillips, worked in the Afro’s archive.

At 14, Webster discovered a box of his grandfather’s negatives in his parents’ basement in Madison Park. There’s Dr. Camper, a local civil rights leader, casting his vote at Douglass High School. There’s Louis Armstrong backstage at the Royal Theatre. There’s Billie Holiday walking down Pennsylvania Avenue with a brown bag in her hand.

“It was almost like I was everywhere my grandfather’s ever been, because he pretty much took a picture everywhere he went,” Webster says. Now 39, he’s in the process of documenting that perspective for the I. Henry Photo Project, an ongoing effort to archive his family’s photographs. “I feel like with more knowledge of history and the past, it’s easier to put stuff together to look at a vision of the future,” he says. So far, he’s scanned about 10,000 negatives, which he estimates to be a fifth of what exists.

Redd Foxx backstage at the Royal Theatre circa early 1950s

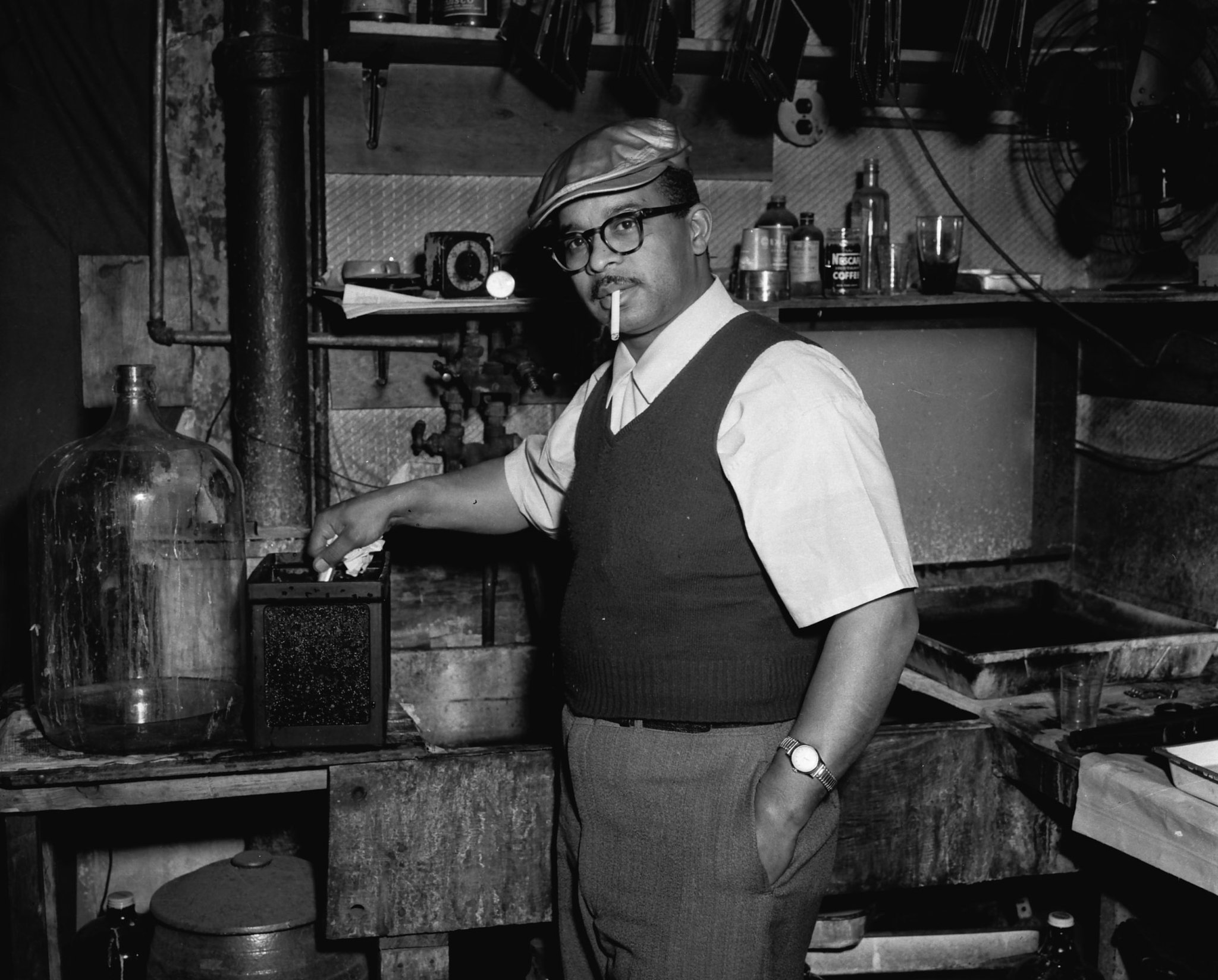

Frank Phillips in the doll hospital circa mid-1950s

Webster Phillips (photo by María Sánchez)

Webster Phillips (photo by María Sánchez)

As he flips through the images, he looks with the trained eye of a second photographer, a vestige of those first outings with his dad. A young girl stands with a crown on her head, a homecoming queen, he guesses. My eye is drawn to her beautiful white dress and the red ring encircling her, a rare chemical reaction from age, but he points out the boys peeking through the fence and from the window which I hadn’t noticed. The hidden histories are what interest him, and they’re also what make the I. Henry Photo Project meaningful.

Webster, who has worked as a high school photography teacher, notes the gaps in education about African American history. “When kids are taught in school, they’re taught slavery, civil rights, Jim Crow.” Beyond the narrative of oppression, he says, “It’s sparse.”

While both his father and grandfather photographed political figures and celebrities passing through town, they also documented daily life for Black Baltimoreans, the unknown figures that Webster wants to uncover. Given the historic erasure of Black communities, Webster is using the lens of his family to shed light on his community.

Frank and Sheila Phillips with The Thinker at Baltimore Museum of Art circa 1955

Frank and Sheila Phillips with The Thinker at Baltimore Museum of Art circa 1955

Unknown woman with Cadillac, Carr’s Beach circa 1950s

Unknown woman with Cadillac, Carr’s Beach circa 1950s

A key component of that is crowdsourcing. The I. Henry Photo Project uses social media (@ihenryphotoproject on Instagram; I Henry Phillips Photo on Facebook) and hosts slideshows at libraries to help identify people. After Webster posted a photo of a family walking down a block with shopping bags in hand, a commenter wrote, “Mystery solved. This photo is of my grandparents with 7 of their 9 children,” adding that the image accompanied a 1956 Afro article titled “The Deans go Easter shopping and it’s a whole lot of fun.”

Webster encourages young people to show these images to their elders as a way to connect generations. With a recent Grit Fund grant, he hopes to hire youth so they can become more engaged with their city’s history, as well as host more community ID sessions and an interactive art show so that each story is fully told.

When I ask Webster what stories he sees in the I. Henry archive, he replies, “the love the community had for each other.” Through snapshots of daily life—documenting both the ordinary and the extraordinary—the Phillips family is taking control of the narrative and amplifying Black history. The I. Henry Photo Project shows Baltimore’s history of resilience in the face of segregation and struggle, along with its joys and celebrations—a truly radical act.

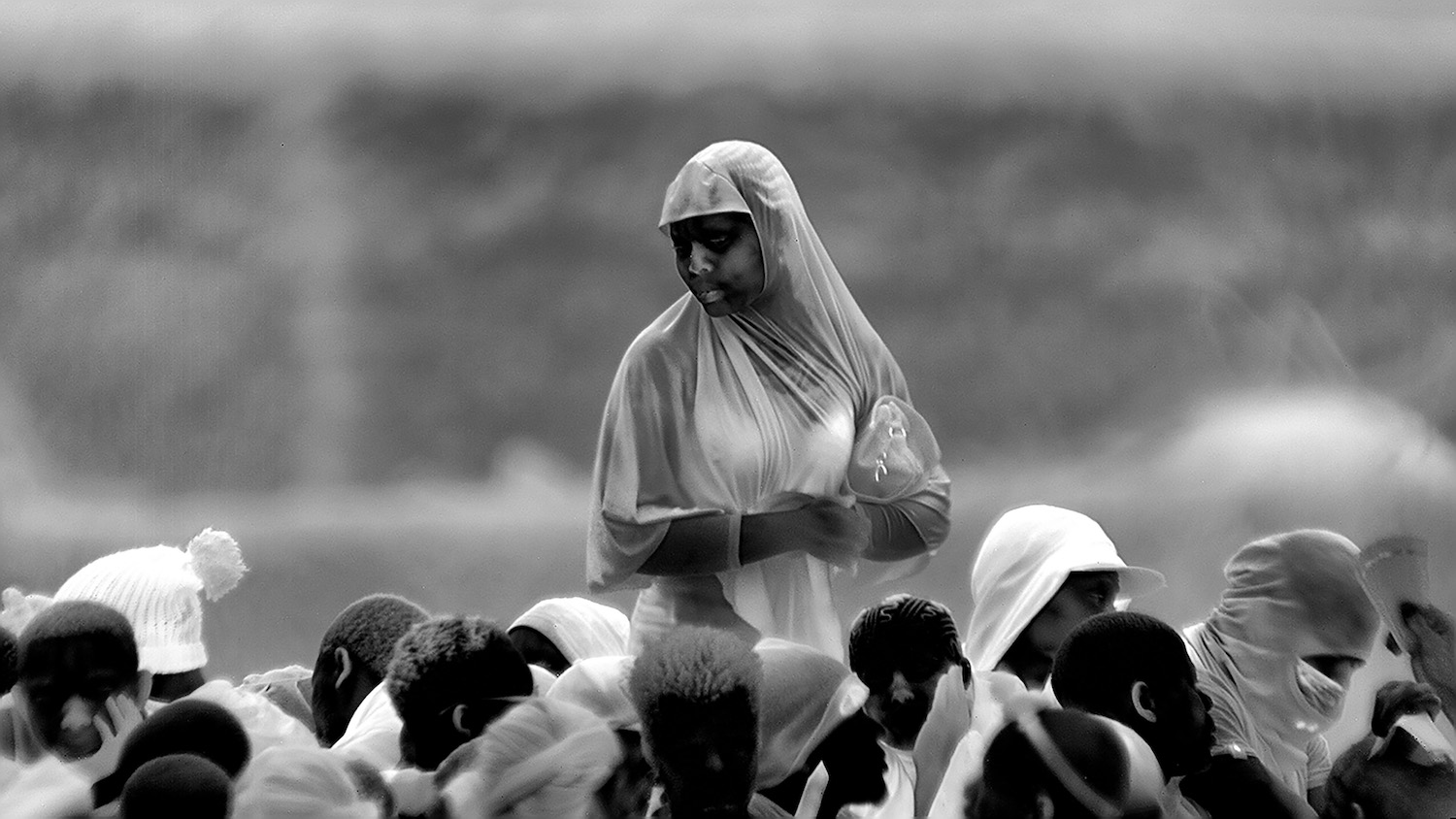

Unknown woman with horse circa mid-1950s

Unknown woman with horse circa mid-1950s

Featured image: I. Henry Phillips Sr. in darkroom circa mid-1950s

Photos courtesy of Webster Phillips except where otherwise noted

This story appeared in BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas Issue 08: Archive.