There is an obvious amount of labor involved in the creation of the gouache drawings, which are impressive in both their scale and detail. What is your process like before you sit down to making the large final drawings? Do you do any preparatory sketches? Do you try out various color combinations? Have you ever made a “mistake” in the process of painting and how did you rectify it?

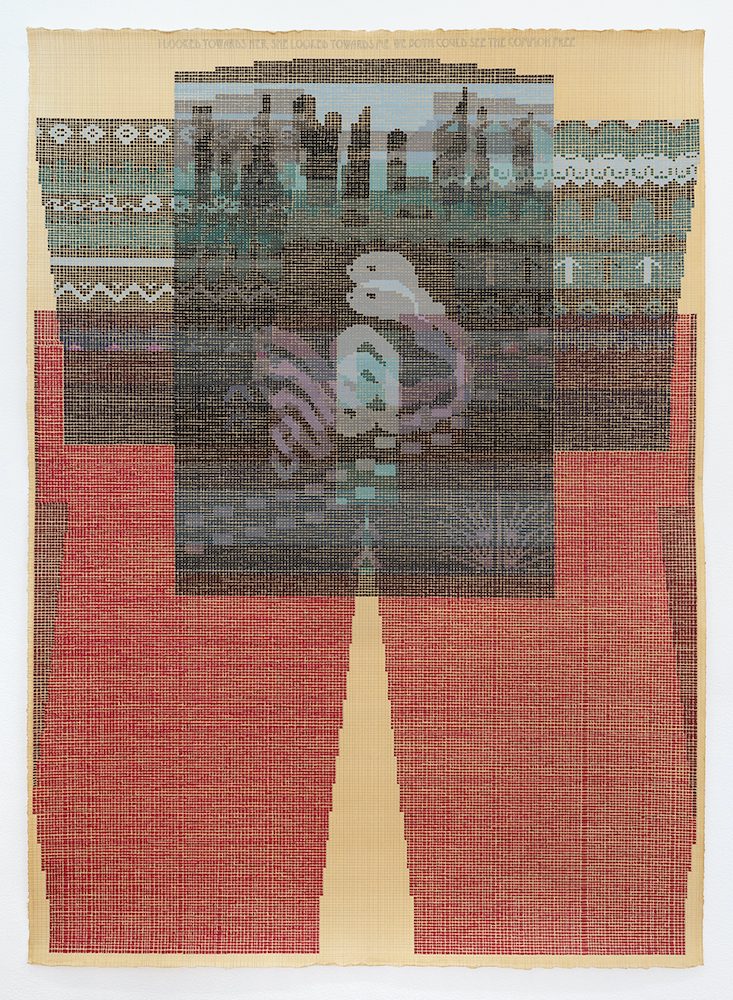

I don’t do any preparatory sketches, which might seem strange, but I think because they are so labor intensive, if I had too much information going in about how one was going to look when it was done, I might not be so engaged in making it. Seeing what color mixes happen, seeing what patterns look like superimposed on top of other patterns is an important part of the process for me. I think this is also related to my brain as a knitter, strangely. I tried, for example, to learn weaving, and the main thing that turned me off to the process was all the setup required before I could get started working. As a knitter, I just start right in, I don’t even usually do the preparatory “swatch” that pattern-writers want you to do to make sure the size of the garment is right. I just want to get moving! With the paintings, I definitely think about the design of it a lot beforehand, like how the pattern pieces might be placed to overlap each other, if interesting secondary shapes could be made from overlaps, but a lot of the 2D design of the piece is actually pretty predetermined by the sweater source image. For example, a raglan sleeve is a different shape than a set-in sleeve, and the size of shapes is based on how large a sweater it appears to be and how fine or bulky the gauge of yarn is.

In terms of mistakes, yes, I definitely make mistakes. If you look at the grid that I initially draw onto the paper, this is the clearest way to look for “mistakes.” I am not a robot and my hand is really imperfect. There are always places in my grids where things get wonky and lines are too close or too far away from each other, but I really like these moments. I think they underscore the fact that drawing is a handmade thing.

This also relates back to knitting because instead of ripping apart a whole garment, a lot of hand-knitters learn to live with intermittent mistakes in knitting repeats, even putting in a deliberate human mistake to make a break from perfection (which is cursed in some knitting lore). If you look at the paintings up close, you can probably see instances where I made mistakes with the painting itself too—or maybe not, because they are actually really easy to fix. Gouache is so opaque that if I mix a hue that is as close to the paper’s color as possible, I can paint the mistaken squares the paper’s color, let it dry, and start over right on top.

More expensive than watercolor and generally more opaque, gouache became a popular medium for illustrators making initial drawings for the fashion and movie industries or fine artists making mock-ups for oil paintings. How did you settle on gouache as the medium to use to make these drawings? What does it mean for these works to be on paper?

I think it is necessary for the paintings to be on paper and to conjure up the sorts of histories that you pick up on: the so-called “lesser” histories of functional painting practice used by illustrators and fashion designers, set and costume designers, knitting designers, Bauhaus weavers, and artists like Anni Albers and Sonia Delaunay. I reached toxicity level with oil painting early on—literally, with the solvents involved, having painted as a student in confined spaces, and then teaching in poorly-circulated oil painting classrooms and student studio spaces for many years—so I was never going to paint oil on canvas without a respirator on.

But more importantly, I also wasn’t interested in painting oil-on-canvas representations of female subjects. I really wanted to try to somehow represent the figure outside of that history, which is patriarchal and which has prioritized Western lives, traditions, and narratives. I relied on gouache to learn Bauhaus-era color theory exercises, and have grown to love its pigment richness so much. Its opacity allows you to really revel in color and color mixing, and the “hand” of painting with it always reminds me of nail polish. Unlike most other paints, you can re-wet dried gouache too, so the little tubes may seem expensive, but you don’t waste it the way you can a lot of other paints.

I love gouache, especially Schmincke Horadam Artist Gouache and Holbein Gouache (not the Holbein Acryla Gouache type—which you can’t re-wet—just the regular). I like these two brands because they seem to be consistent with their use of quality pigments and their paint doesn’t have issues with transparency. You can mix gouache brands together, but some also have this weird sticky quality that I don’t like (one brand puts honey in their gouache), but both Schmincke Horadam and Holbein lay down a really nice smooth, matte surface. Another painting recommendation: I also love real porcelain mixing trays, the ones that have rows of deep, tiny little reservoirs where you can mix paint. Because they are porcelain and not plastic, you can just let the gouache paint dry in them and re-wet premixed colors later really easily, and then set the whole thing in a slop sink to soak in water for easy clean up.