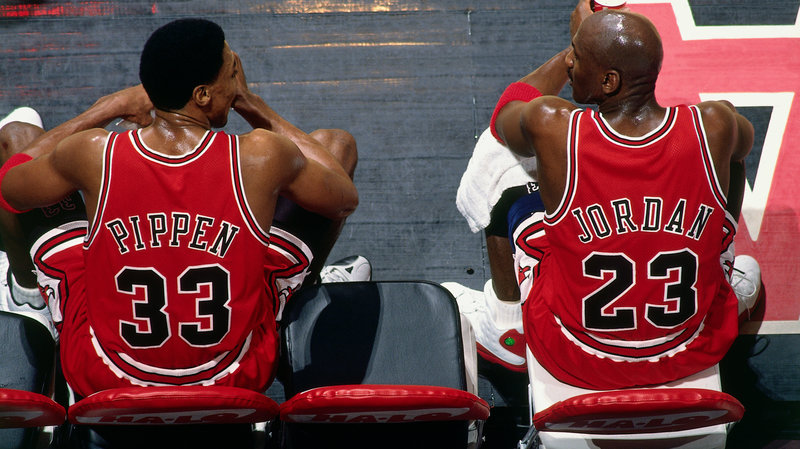

Look, I could totally watch a montage of Michael Jordan dunking over the gangly white goofs/legends that mostly make up the Boston Celtics set to LL Cool J’s “I’m Bad” for hours straight. That is to say, the ten-hour ESPN/Netflix documentary The Last Dance, which in episode two (of ten) has a brief sequence that shows just that, is made for dudes like me. It is about basketball, that is all it needed to do to get me watching. That’s the sick thing about sports, they don’t have to be good or compelling, they just have to be. And there aren’t any sports happening right now which makes this ambitious, meandering documentary that uses the 1997-1998 Chicago Bulls season (the last one with Jordan and, therefore, the last time the Jordan-led team won big) as scaffolding for a larger story about Michael Jordan, the closest we all can currently get to sports.

There have been other attempts to do sports during the pandemic. A few weeks ago, there was a “virtual” tournament in which NBA and WNBA players went about a game of H-O-R-S-E communicating over live streams from their phones, though it mostly just had me, as I watched players in their personal gyms or hoops outside, once again noting the income gap between the men of the NBA and the women of the WNBA. Man do those NBA guys have nicer things.

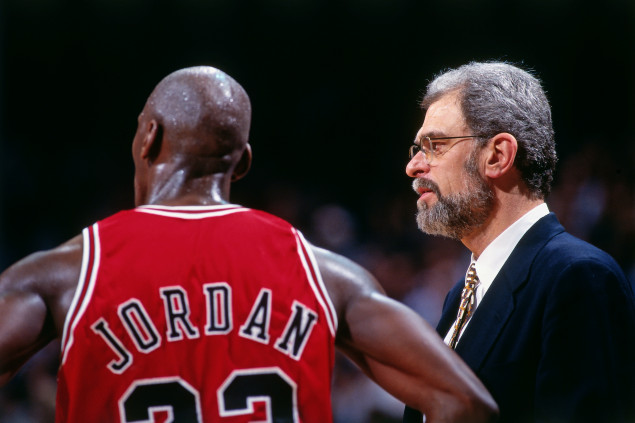

And The Last Dance has something for those who can’t subsist on simply seeing sports happening on a screen—it also chips away at the idea of Michael Jordan and shows him to be a driven, thoughtful, complicated man, brand, and bully. Jordan, who provided director Jason Hehir a lot of access, comes off more like a more normal person than he usually does, and the sheer volume of footage of Jordan here also unravels whatever image he’d like to present. A moment where he lectures young Bulls player Scott Burrell for not taking the game seriously and says he’s an “alcoholic”—all presented in jest but everyone knows he means it on some level—is just awful to watch. That Jordan—who as The Nation’s Dave Zirin noted, ostensibly had final cut here—allowed that clip says something about how he sees himself and how he’s willing to let others see him.