Sarah Marriage has always worked in traditionally male-dominated fields. With an education in architecture and a background as an engineering drafter, she is no stranger to environments where women are expected to represent the minority. But it wasn’t until she entered the world of furniture making that she registered her gender as a distinct point of conflict in her profession.

“As much as I wanted to avoid talking about my gender with my work—because I didn’t see that my work was really anything about gender—the more society just kind of pushed it in my face,” Marriage said. She recalls displaying her work at trade shows and being asked if her husband made it. Nevermind that she doesn’t have a husband.

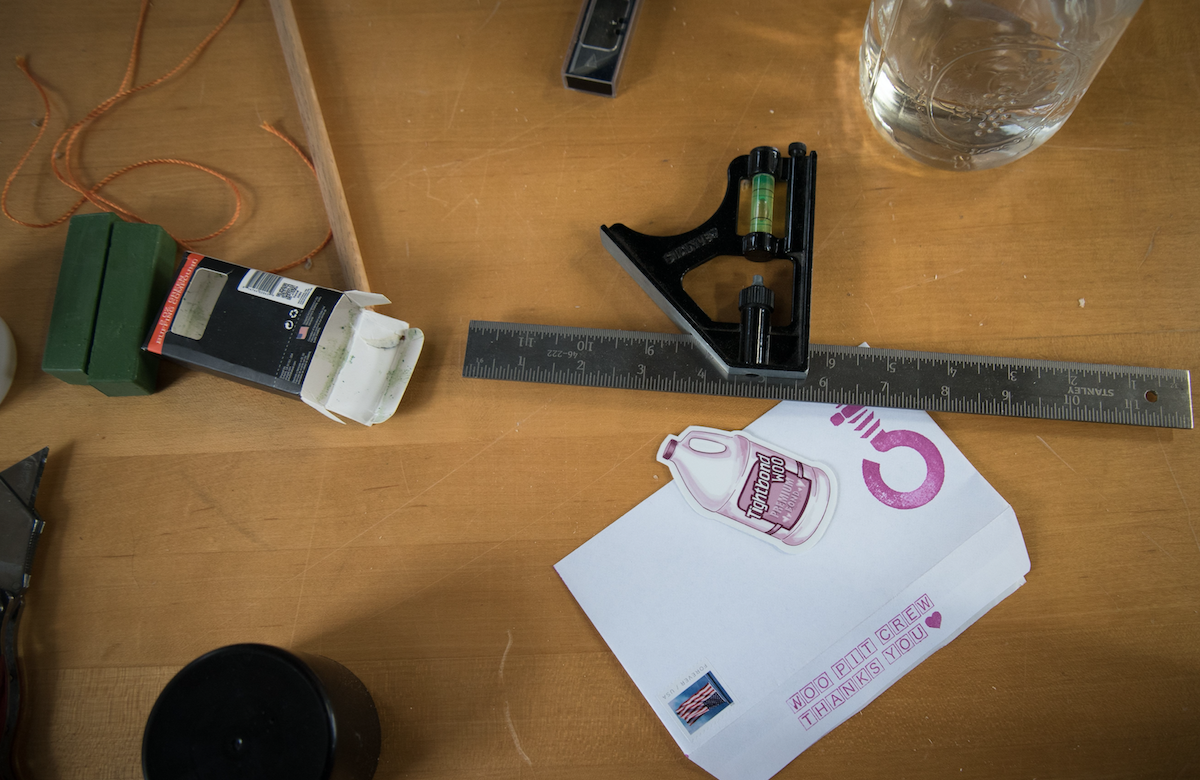

The widespread alienation, harassment, and unmitigated exclusion that comes with not being a man in a typically hyper-masculinized field prompted Marriage to develop a necessary alternative. With support from a John D. Mineck Furniture Fellowship grant, she developed a woodshop specifically for women and gender-nonconforming craftspeople to work and learn new skills. In 2017, Marriage opened the shop doors in Baltimore’s Woodberry neighborhood, naming the space A Workshop of Our Own (or WOO)—a nod to Virginia Woolf’s canonical essay which points to the material and social limitations that have impeded women’s ability to thrive creatively throughout history.