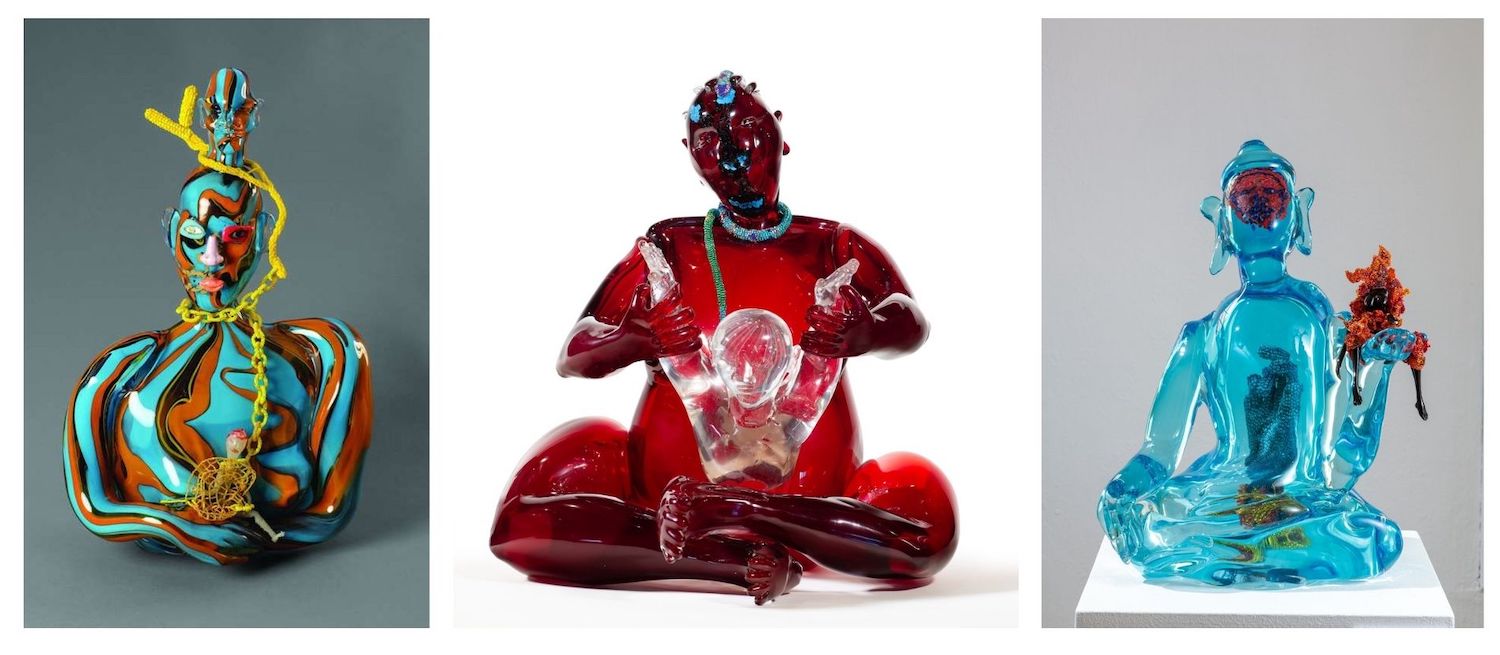

Although he expressed a commitment to focus on global and local artists equally in a 2016 interview with BmoreArt, museum director Christopher Bedford has instead closely followed the trends of the global art market. He described the “visionary reckless speculation” of Etta and Claribel Cone, whose investment in the undervalued artists of their time that they admired has made the BMA a world-renowned institution, as his goal, but what I am observing is an institution paying much higher prices than necessary, making risk-averse decisions about collecting that do not reflect the region’s diverse ecosystem of artists, and sending almost all of its acquisition dollars outside of the state to be invested in other artists, galleries, and cities.

I suspect that one reason that many museums currently focus on collecting art from globally vetted artists is a skewed perception of value where auction prices, sales records, and global reputation are the primary indicators of lasting cultural worth, and the reality is that most Maryland artists do not have public auction records or price points relevant to a global art market.

However, confusing the market value with the actual value of work of art is a huge mistake. This is a crutch for investors who do not trust their own vision and ability to steer the art market rather than follow it, or for those who purchase art like stocks they believe will appreciate.

In the case of a museum, where works are rarely sold off and it is against the rules to sell art based on market value, this really shouldn’t have much bearing on collecting decisions. A museum collection should not be about the personal taste of a few individuals who currently work there, who will be moving on to a different position at a different institution in a few years. A collection should be about research, relationships, and an authentic commitment to the unique culture of a place. To truly diversify this collection, bigger picture thinking is required from BMA leadership. Curators need more agency to conduct research locally and advocate to collect artists who live and work here, the artists who can properly tell a unique Baltimore story as only the artists of this place can.

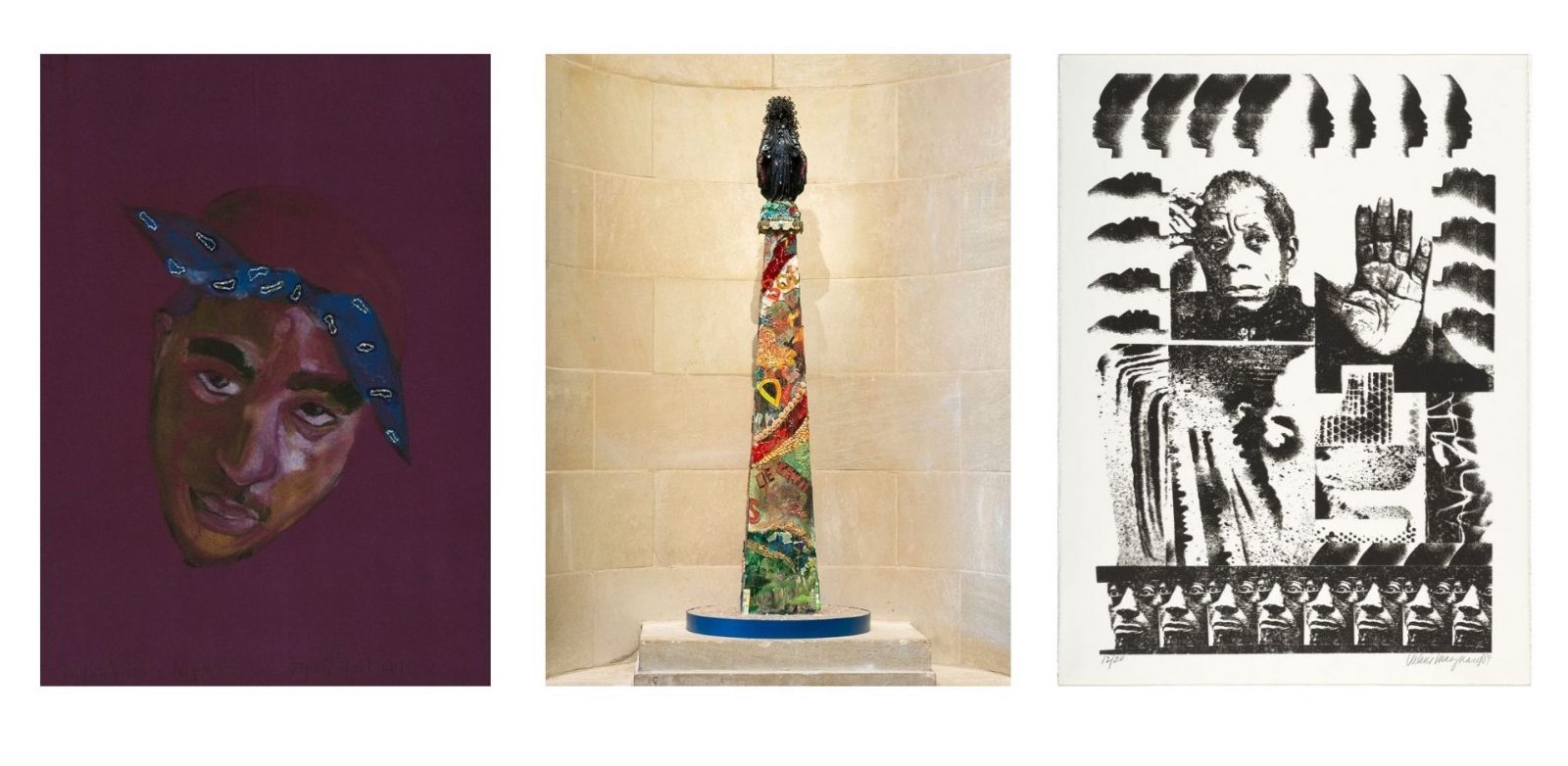

It’s a letdown to visit museums across the country to see all the same globally vetted artists with New York mega gallery representation on display. It’s not that these artists aren’t great, but I want to visit a museum to understand the unique history and culture of a place, to understand this diversity through the work of regional artists, materials, and trends. The BMA is exhibiting works by artists from the region like SHAN Wallace, Elissa Blount-Moorhead, and Jo Smail, and I applaud this investment, but these exhibitions are ephemeral. Once they are over, their art will be gone from public access unless the museum collects them.

I believe that Baltimore and the state of Maryland have a pivotal story to tell the rest of the world, and that our museum has an ethical and professional obligation to tell this story by collecting, preserving, and exhibiting the artists who live and work here. It’s not as if our artists haven’t earned this type of coveted and valuable recognition—it’s just that we have never had a robust art market to validate their success. Who better to begin this regional market elevation than our local museum which has the capital to invest and the clout to influence collectors?

Perhaps I just don’t understand the economics. After all my years of research, the global art market still appears to me as an expensive mirage, a bejeweled Cartier snake with giant emerald eyes chasing its own tail, a conga line of wealthy folks in asymmetrical linen pants and funky glasses who are constantly looking away to the next big thing, constantly traveling and unaware of the incredible, world-class art being made right here right now. Maryland has an expanding list of Guggenheim fellows, Joan Mitchell grantees, Rome Prize Fellows, Pollock-Krasner recipients, and artists whose work is being collected in museums across the country and the BMA is missing out on the opportunity to collect their work now.

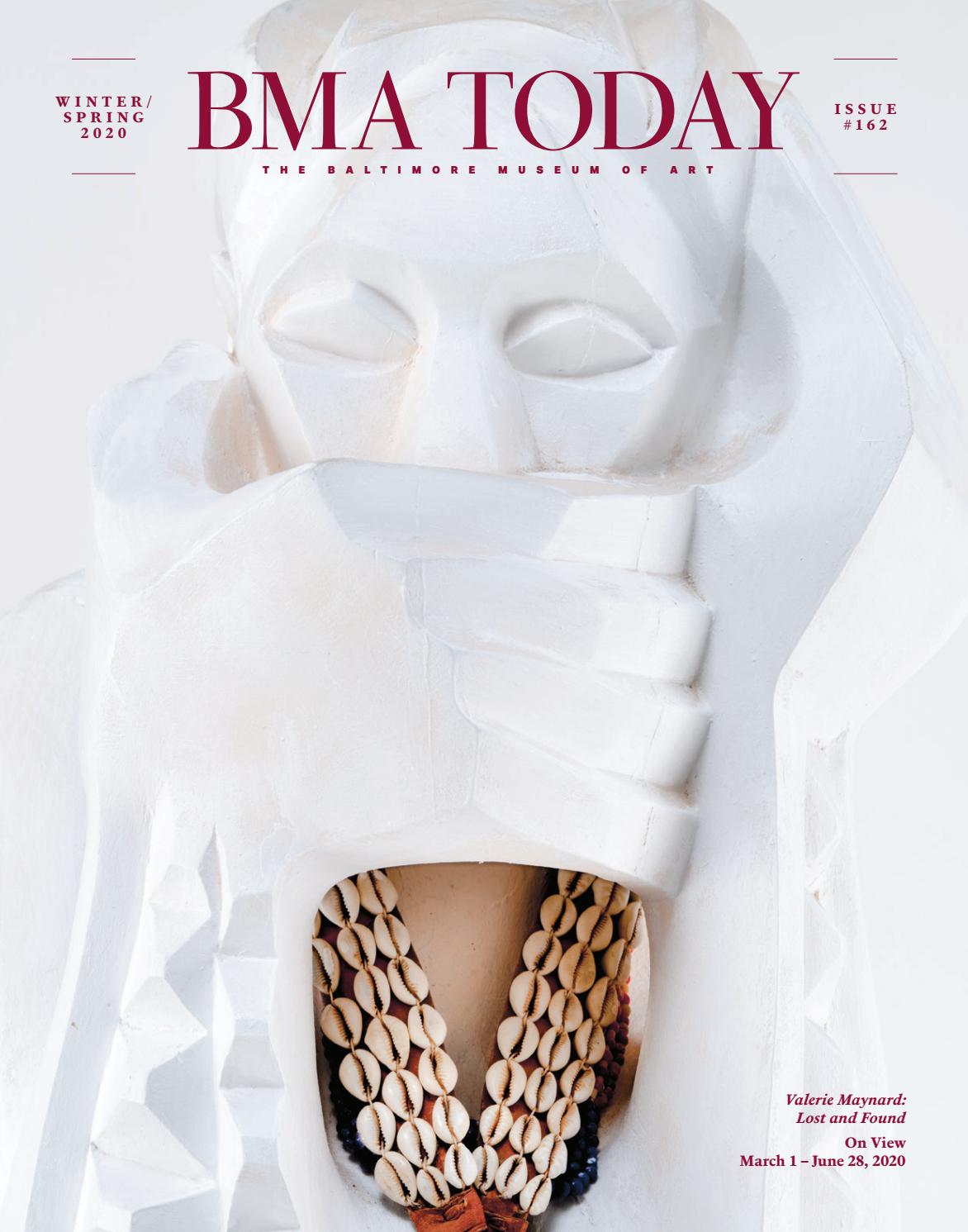

For anyone who says they do not know where or how to start conducting researching and collecting Baltimore- and Maryland-based artists, BmoreArt is here to help you! We have released ten print journals full of excellent and collectible artists since 2015 and a reading list to help you select the perfect regional artist to diversify your collection. You can discover regional galleries through BmoreArt’s online resource guide, calendar, and weekly event listings. You can conduct research via the Baker Artist Awards website, GBCA’s newsletter, BOPA’s distinguished list of Sondheim winners and finalists for the past fifteen years, the Rubys Artist Grants, the Maryland Artist Registry, and a number of other local art organizations, residency programs, and exhibitions that highlight the achievements of artists from the region.

I have invested so much time and energy over the past few years trying to understand how and why art is collected in order to better advocate for the acquisition of the work of a number of the most successful artists of the region. There are a growing number of artists with the talent and work ethic needed to become international sensations, artists whose work we will soon not be able to afford if all goes well, and others whose work has influenced multiple generations of young artists and whose legacy should be represented in the BMA’s collection for perpetuity.

We will all benefit from collecting the art of our place and time, especially our Baltimore museum. The time has come to think strategically about how to diversify the collection to be more inclusive, equitable, and authentic to this unique place and time, to properly value the artists of the region who are our greatest treasure. I’m not sure how much more appealing I can make this to museum leadership, but clearly the art math is beyond me.