How can we make working from home work for us as creatives?

Have a Morning Routine

Many people have written about the power of a morning routine. Writer and self-help guru Julia Cameron, of The Artist’s Way fame, has written about how her routine has changed as she’s gotten older, Lizzo has spoken to New York magazine about her obsession with watering herself every morning, and Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop has an entire column dedicated to what working women do when they wake up, among the legions of blog and news outlets that have covered the topic. What other people do in the morning is fascinating to us, and if you’re looking for inspiration, it’s out there in many a listicle or vlog.

But to back up a moment, what is a morning routine, and do you already have one? Most likely, yes, you already have a set of tasks that you do in the morning. But is it the most optimal series of activities for setting up your day to do the work you care about? Is your morning routine lying in bed and looking at your phone until you feel awake enough to make coffee? Is your morning routine tackling your email inbox right away? Do you workout first thing in the morning?

Consider this: the morning is the most creative time of the day for most people, and it is the time of day when willpower is at its strongest. Numerous experts suggest organizing your day to tackle your most challenging tasks first thing in the morning. Of course, it isn’t always possible to do whatever you want first thing in the morning—many of us have children or pets who require care upon waking—so think about how to balance self-care tasks along with familial obligations.

How can you make your life easier to manage with a little advance planning? Some small examples: Are you someone who hates waking up? Buy a coffee machine with an automatic timer so the knowledge that there is coffee already waiting for you motivates you to get dressed. Are you someone who aspires to work out first thing? Lay out your workout clothing and fill your water bottle the night before. Are you doing anything immediately when you wake up that could wait until later in the day? If you feel constantly rushed, consider where you might be wasting time in the morning on tasks that could happen later when you feel more alert—a classic example of this is preparing lunches the night before. Finally, consider if you can wake up any earlier than you already do in order to approach your day more deliberately or, if you prefer, more leisurely.

If you’re at a loss as to how to organize your routine, some basic building blocks that are effective for many people include making your bed, taking a shower or bath, having a gratitude practice, moving your body, caring for children and pets, preparing food for the day, eating, reading, meditating, or engaging with a creative practice. You can include as many or as few of these that make sense for you. Your morning routine can be a few seconds or it can be a few hours, it’s totally up to you. But like any other good practice that you want to become a routine, you should design something that you can repeat. If you know you want to exercise and eat a full breakfast every morning, it’s probably not practical to also plan to take a bath and read a chapter in a book. Decide how much time you have each day, how early you can commit to waking up, and which activities are of greatest importance.

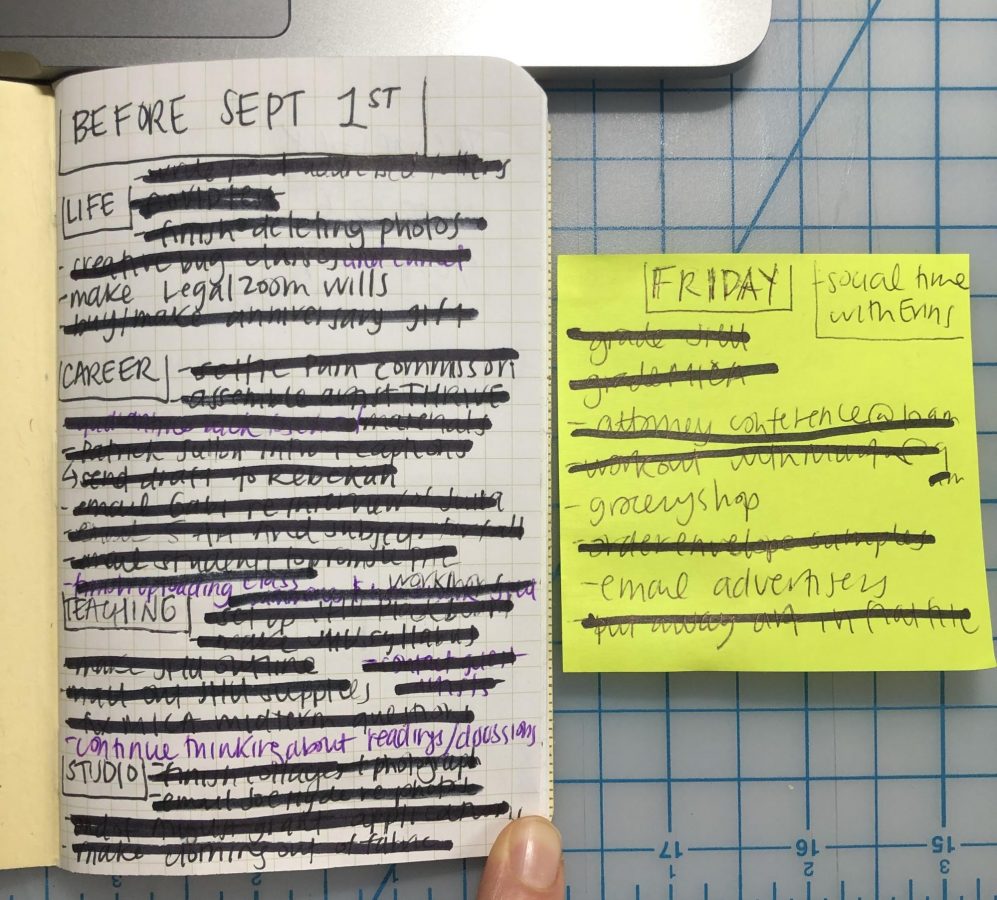

If the examples above are not enough inspiration, I‘ll share my own quarantine morning routine, which is the result of several changes, and I imagine it will continue to evolve as my lifestyle does. Right now, I wake up and put on workout clothing. I walk our dog, Theodore Roosevelt, and try to feed him (his morning routine includes ignoring his food and watching squirrels out the window of our rowhouse while our cat, Charlotte, tries to eat his dog food). Then I pour myself a cold brew, which I made the night before, and make a full breakfast. I typically eat my breakfast while watching 15 minutes of a truly trashy television show. I used to open up emails during breakfast, but now I like to wait a little longer and give myself this time to relax. Since I no longer leave the house for anything but essential errands, I often take a few minutes to clean up the living room and water the plants. Tackling small household tasks in the morning helps me feel like they are manageable and not something waiting for me after a full workday. I clean up my breakfast and, depending on what day it is, I either answer pressing emails or work out with a friend over FaceTime. I have alternating activities following my daily routine because I have several different jobs and I’ve found I value the flexibility to choose what I am doing first based on what feels like the hardest task and what else I have scheduled for the day.

[Image: Author’s dog, Theodore Roosevelt, ready for his walk but never for his breakfast.]