Matrilineal societies in Africa celebrate the mother as a guardian, saint, and unstoppable creative force. They recognize that mothers share a bond with their children that transcends physical life and death. What we understand as the role of “mother” within the matrilineal belt of Africa is bigger than one person’s gender. In fact, it takes many people to fulfill the roles of motherhood in their entirety.

The Baltimore Museum of Art’s exhibition, A Perfect Power: Motherhood and African Art, is filled with ritual objects that celebrate the creative force of the mother. The show’s broad subject matter, sculpture from African matrifocal societies, offers a mixture of sociology and art that isn’t easy to fit into any genre or category. The exhibition compelled me to assess family and gender roles very differently from what I’m used to in the West, offering a transnational message that can teach us how feminism and advocacy can appear in different forms that are culturally specific. Within African societies where the mother has a more dominant role, neither the mother nor her related rights are seen as a liability in a man’s world. Instead, motherhood and child-rearing are not individual responsibilities, but functions of the community.

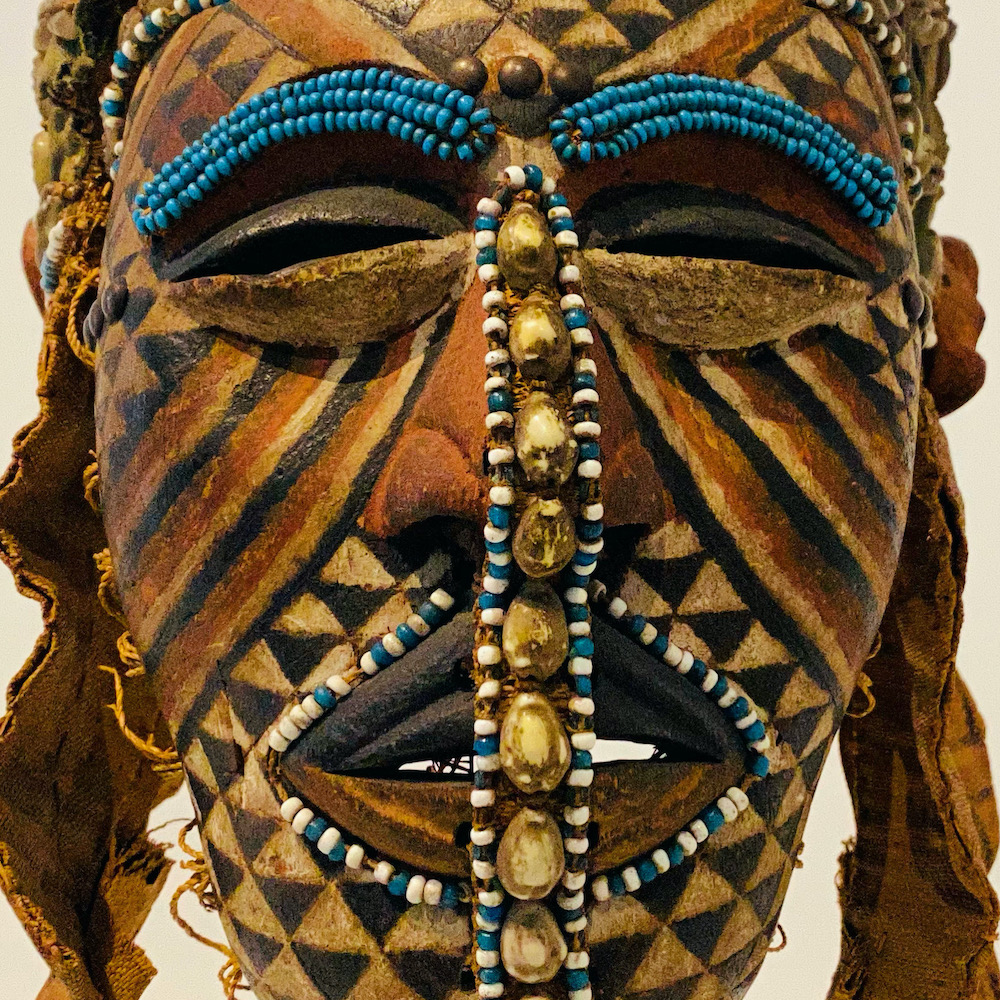

The call to mother changes faces—and masks—in different circumstances, societies, and ceremonies. According to the museum, most of the objects on view in A Perfect Power were made in the 1900s, and used by men to access ancestral power that reached far beyond that of colonization.

The original artists who created the nearly 40 pieces on display are not as well-known as their Western custodians. One-third of the objects came from the BMA’s permanent collection, another third came from private collections, and the rest came from other institutions, such as the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Most of the African societies represented were located in Zambia, Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Guinea. Collectively, the objects in the show celebrate the role and responsibilities of “mother,” both within and in defiance of a Westernized context.

By their nature, the objects themselves can only give us a partial view. “A lot of these objects only have power and meaning… within a performance context,” says Kevin Tervala, the BMA’s Associate Curator of African art. “This mask doesn’t mean anything unless it is danced with the raffia costume, with the drumming, with the stilts that the performer is wearing. A lot of the power that is inhabited in these artworks is located in a multisensory or artistic complex that hasn’t been translated.”