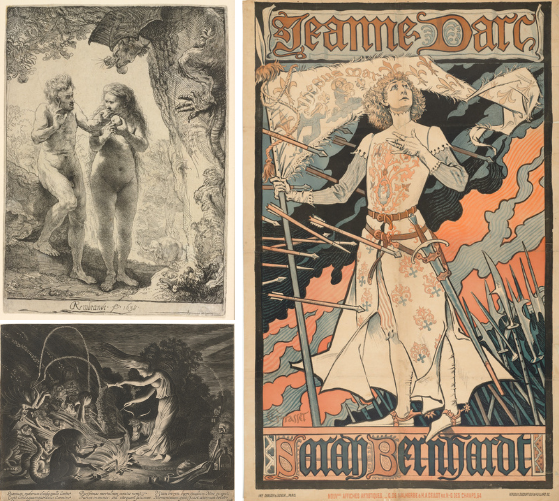

At its core, Women Behaving Badly: 400 Years of Power & Protest (at the Baltimore Museum of Art through December 19) consists of a two-part argument. In the show’s first room, whose walls are painted a dark purple, an array of works depicts legendary female troublemakers, from Medusa to Eve. The effect is spooky and oppressive, and the lesson clear: For millennia, fundamental Western narratives have positioned women as transgressive, dangerous, and unnatural.

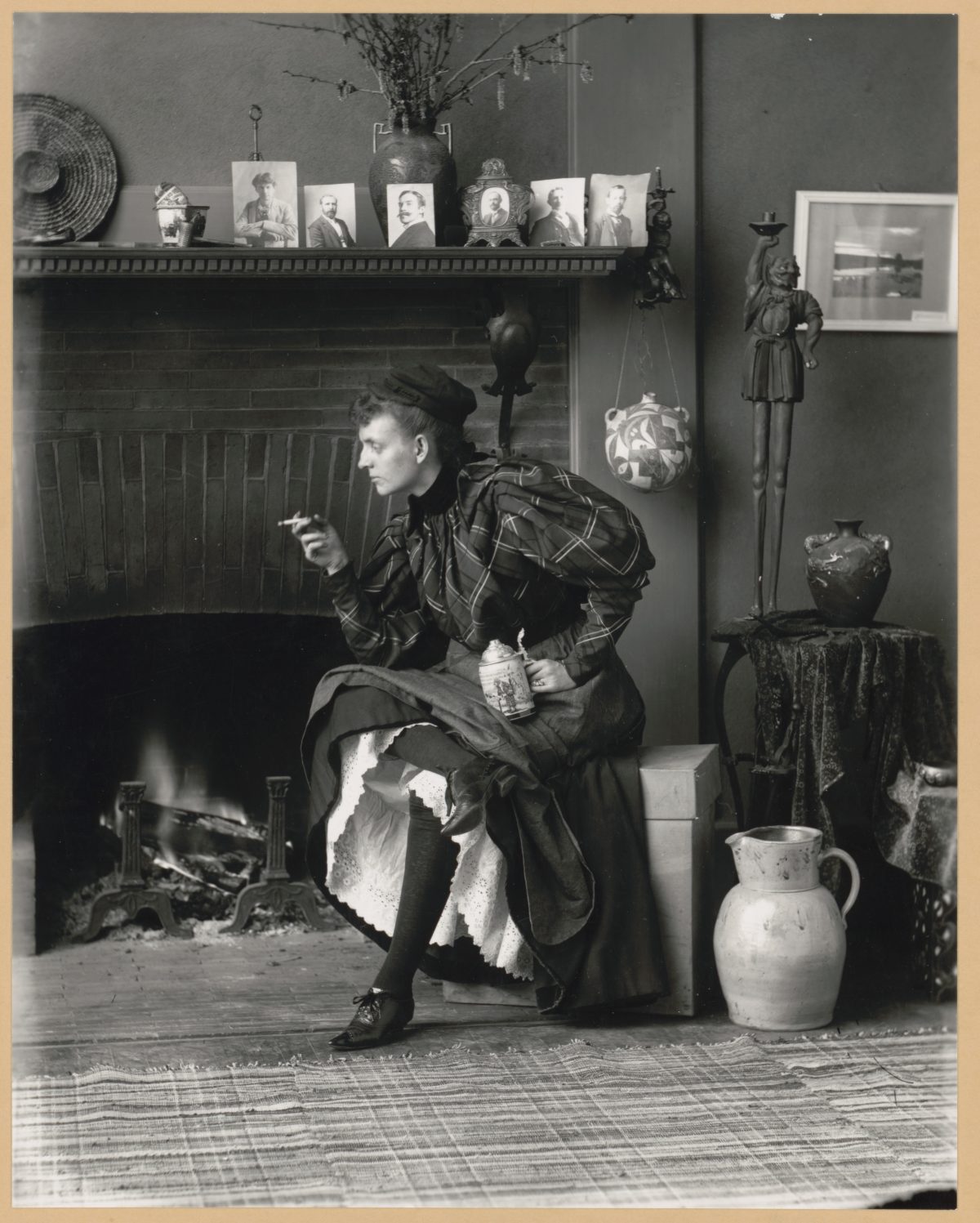

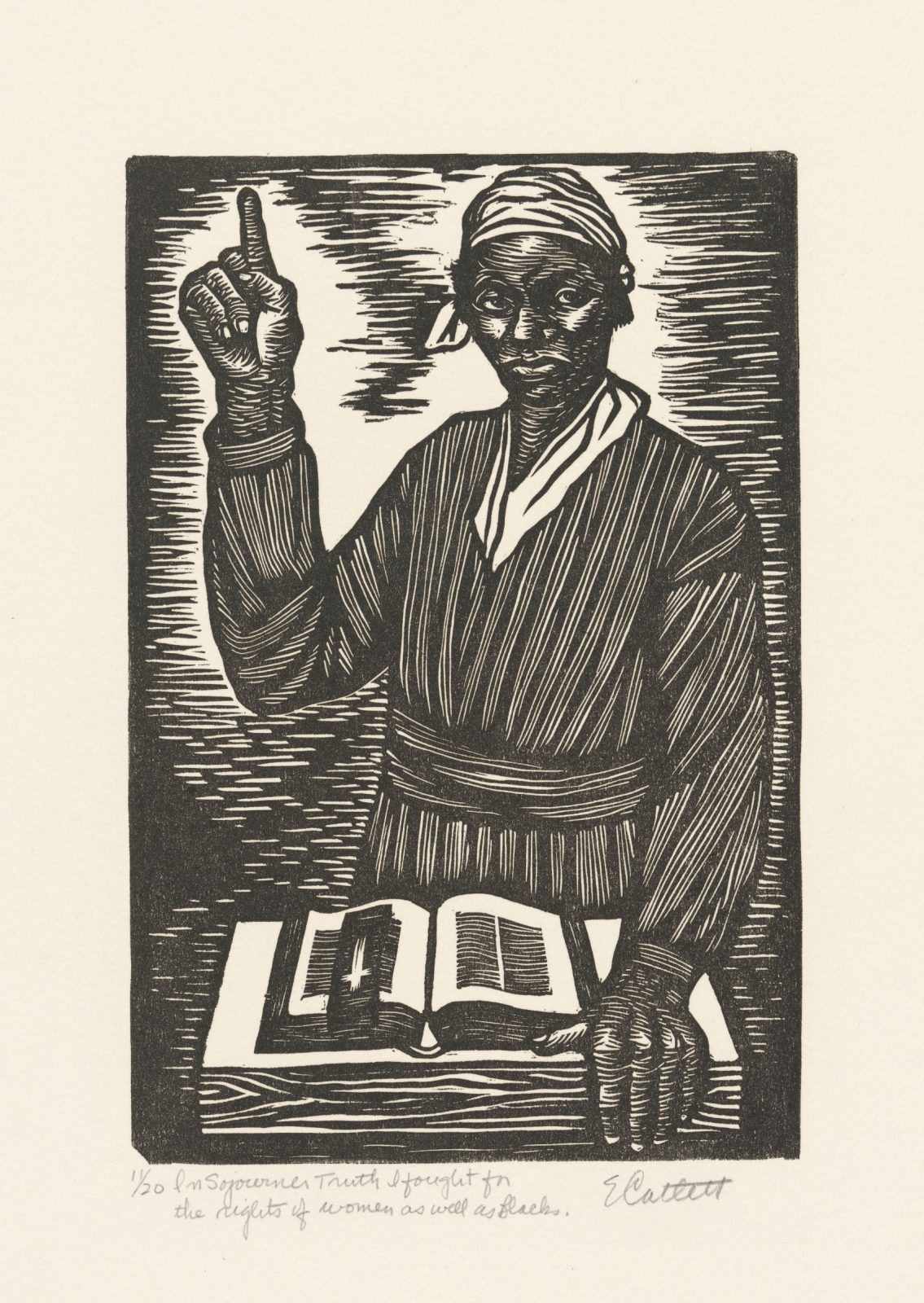

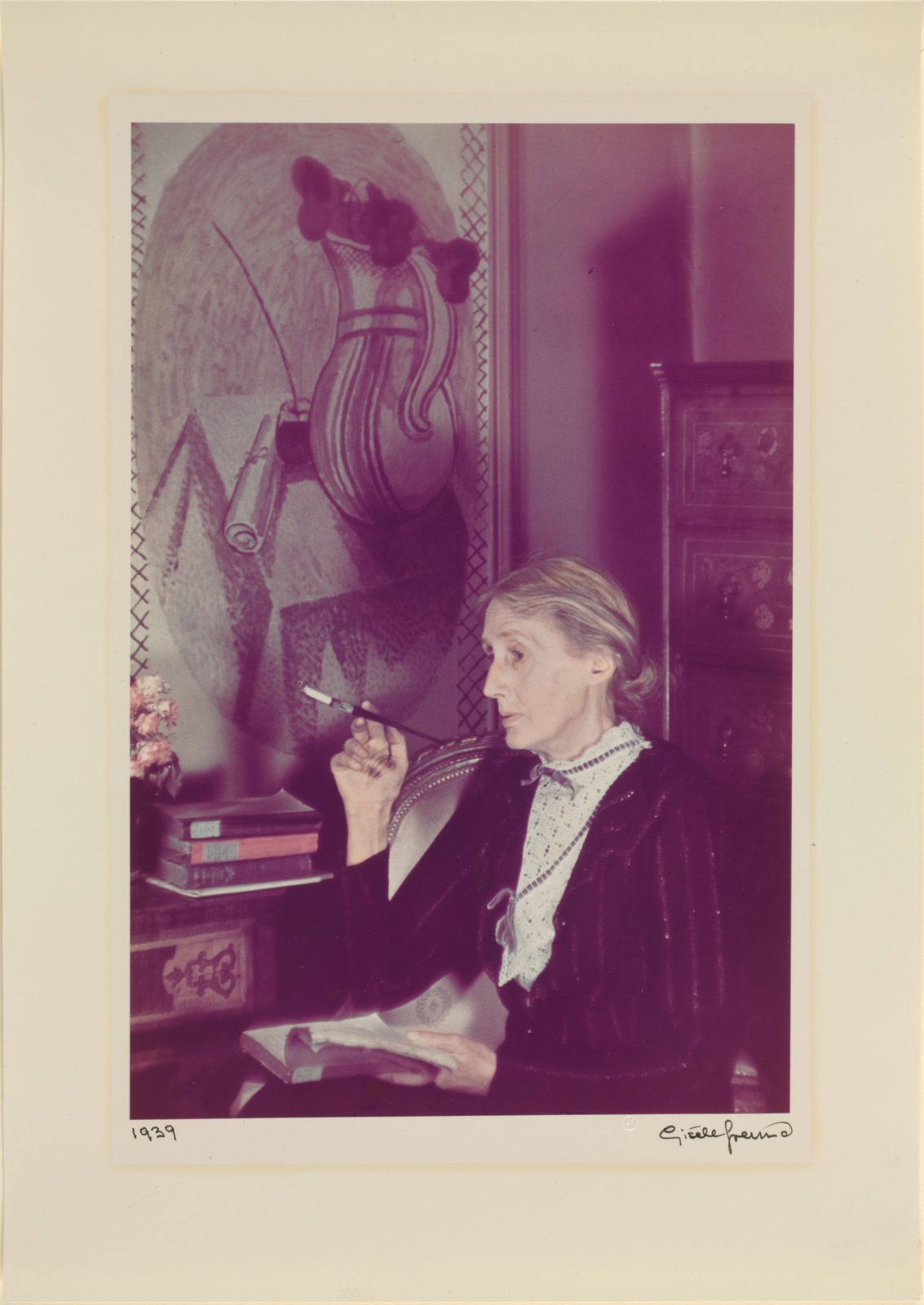

But the second room, outfitted in a lighter lilac gray and featuring dozens of works by and about historically significant female performers, artists, and activists, offers a very different proposal. Perhaps transgressive behavior, these powerful objects cumulatively suggest, is exactly what is needed in order to effect change in a system long predicated upon the estrangement and vilification of women.

Curated by Andaleeb Banta, the show was initially scheduled to open in 2020, in conjunction with the centennial of the ratification of the 19th amendment, which nominally gave American women the right to vote. Its scope is correspondingly delimited, as the 77 works date from a 400-year period, from the Renaissance to the early 1900s. No Zanele Muholi photographs or #WoYeShi screenshots here, folks; this is a sustained look at gynophobic tendencies in early print culture and the eventual rise of first-wave feminism.

Admittedly, there are potential risks in such an approach, which deploys works of art as illustrations of a teleological narrative that verges on the simplistic: Did the long shadow of misogyny really disappear with the advent of universal suffrage? Please. And yet, despite the limits of such a didactic, commemorative structure, this show is richly rewarding, due in large part to a range of rarely seen objects and some truly clever juxtapositions.