Jessica Gatlin is learning how to be patient with herself. For the self-declared overthinker, the pandemic provided an opportunity to slow down and take stock of her artistic practice and newly transplanted life. Gatlin is relatively new in town; she first moved to the College Park area for a year to take a full-time faculty position in the Print and Extended Media Department at the University of Maryland, and then purchased a home in Baltimore in June 2020 with her husband, the artist Brandon Donahue.

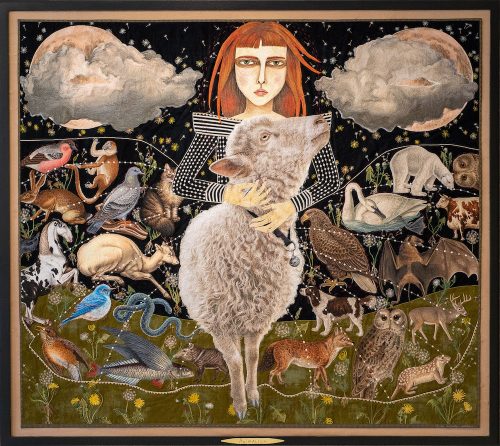

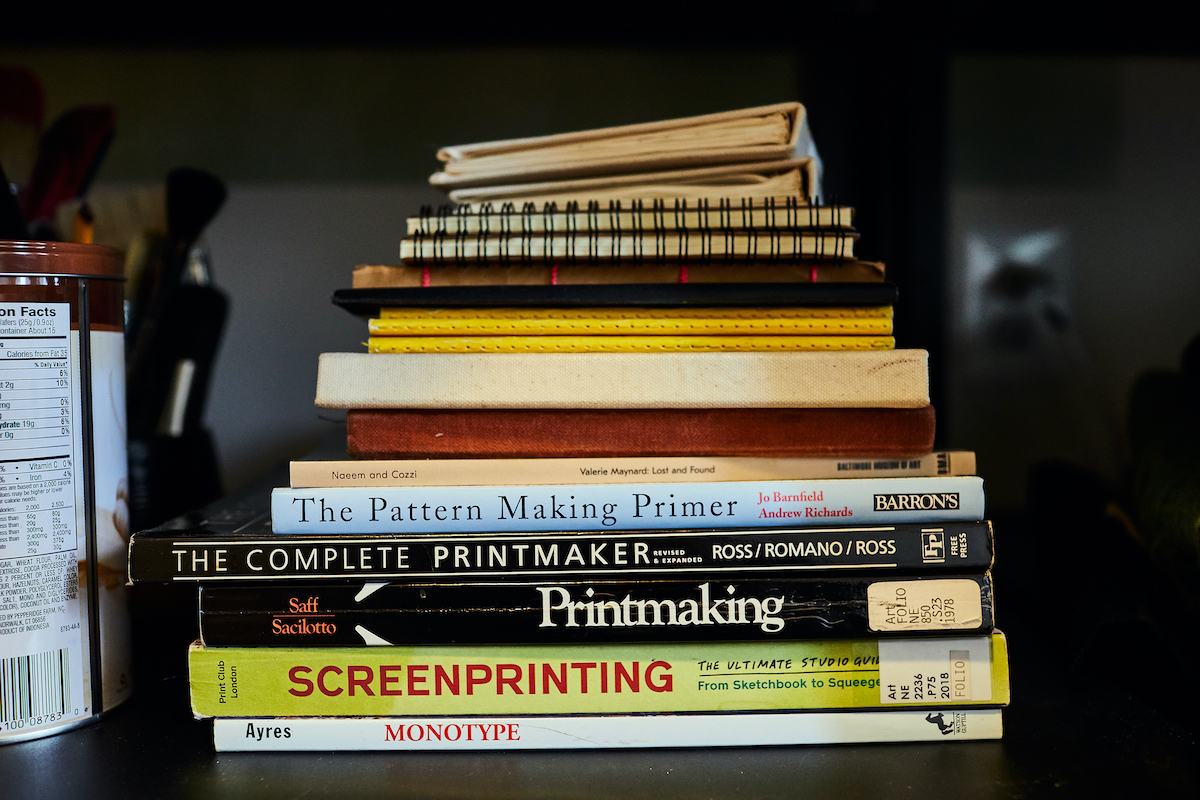

The interdisciplinary artist approaches her work “from a standpoint of print theory” even though not all of her work manifests as prints. Her childhood was rooted in a matriarchal tradition of craft and DIY practices passed down to her from her mother and grandmother. Material is important for Gatlin, as it is for other practitioners who use a mixture of media and approaches in their artwork. But material is not the origin of most projects for Gatlin. Instead, “most of the time, the ideas come first,” she explains. “It’s usually an idea that won’t leave me alone. Grudgingly, I’ll do it. And then it turns out nice.” With patience and an open-ended approach, she has found a way to blend together “high and low” aesthetics alongside sewing, which is a cornerstone of her work “typically relegated to this whole other world” of craft, Gatlin explains. To elevate the way her sewn garments are discussed, she says, “sometimes I call my garments ‘paintings’ or ‘sculptures.’”

Gatlin is cognizant that her work, which spans so many media and styles, “probably looks all over the place sometimes because I haven’t found that harmony.” But it’s part of her process to look at the same big idea in different ways as she considers it from every angle. A running theme is her examination of systems, into which her tangible art objects are going to then participate as commodities, for better or worse.

In the 2018 piece Systemic Trapping(s), Gatlin focused on the common cheese ball as a symbol for 1990s aesthetics and white supremacy. In the installation, a video plays of Gatlin consuming the snack in a room where they are also on the floor to be stepped on by the viewer. “Cheese balls represented that same sort of lie or that same falseness [as dangerous systems],” Gatlin explains. “It’s bright and it’s attractive and you think that something that attracts you is good for you, or you would at least think that sort of thing is not there to harm you. . . . They are delicious and weird, but at the end of the day, if I eat too many, my tongue is raw and my fingers are covered [with] dye and that isn’t necessarily great.” She sees the beguiling food as a “metaphor for all the things that we take in that aren’t true, like white supremacy and capitalism and patriarchy,” and how those systems affect our own beliefs about ourselves. “For me, rejecting and crushing them was a way to let go of some of that and try to re-establish a healthy gut/brain communication,” Gatlin says. “Overall, it’s about self-healing or self redirection, and also just trying to get people to take some time with themselves to think about what things are inside you that aren’t true.”