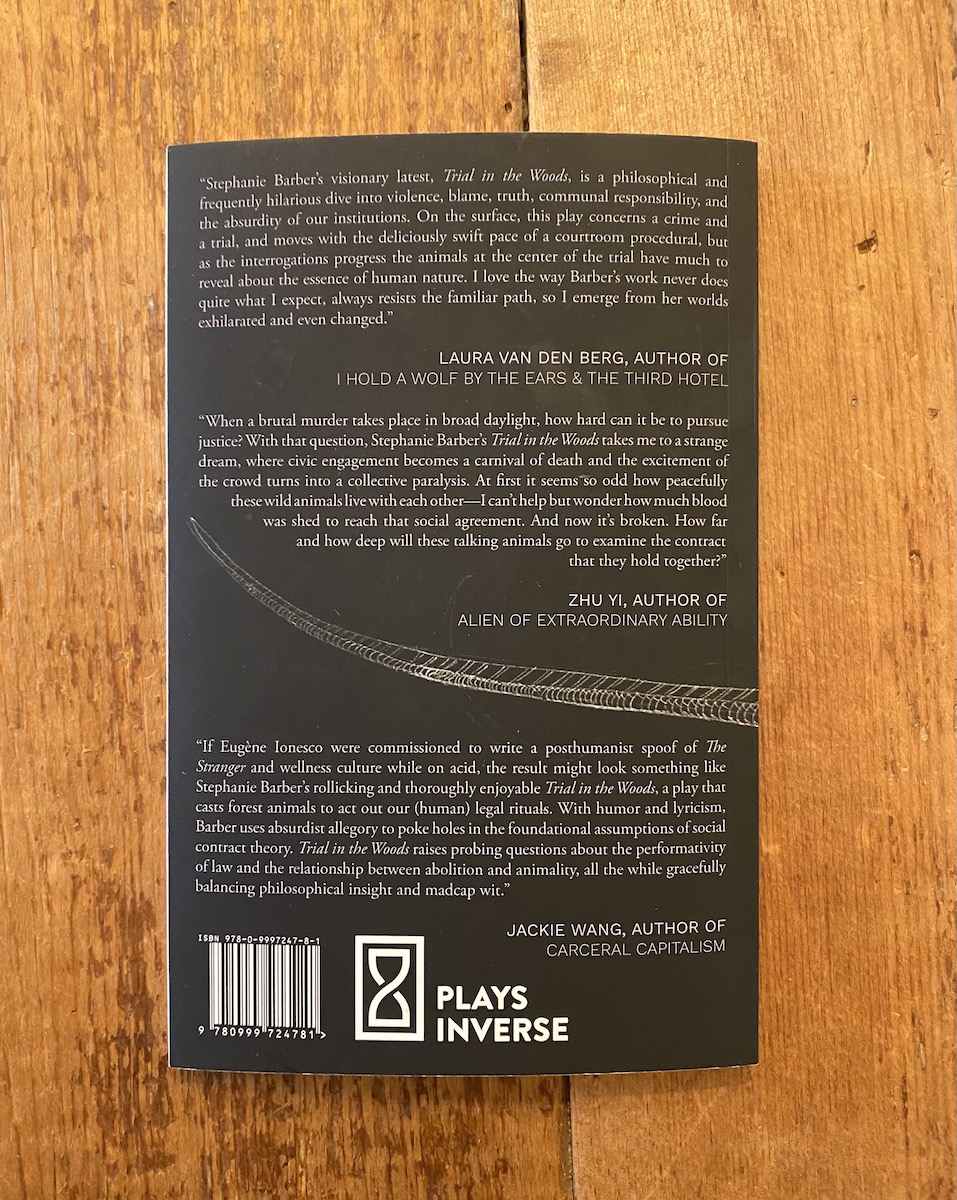

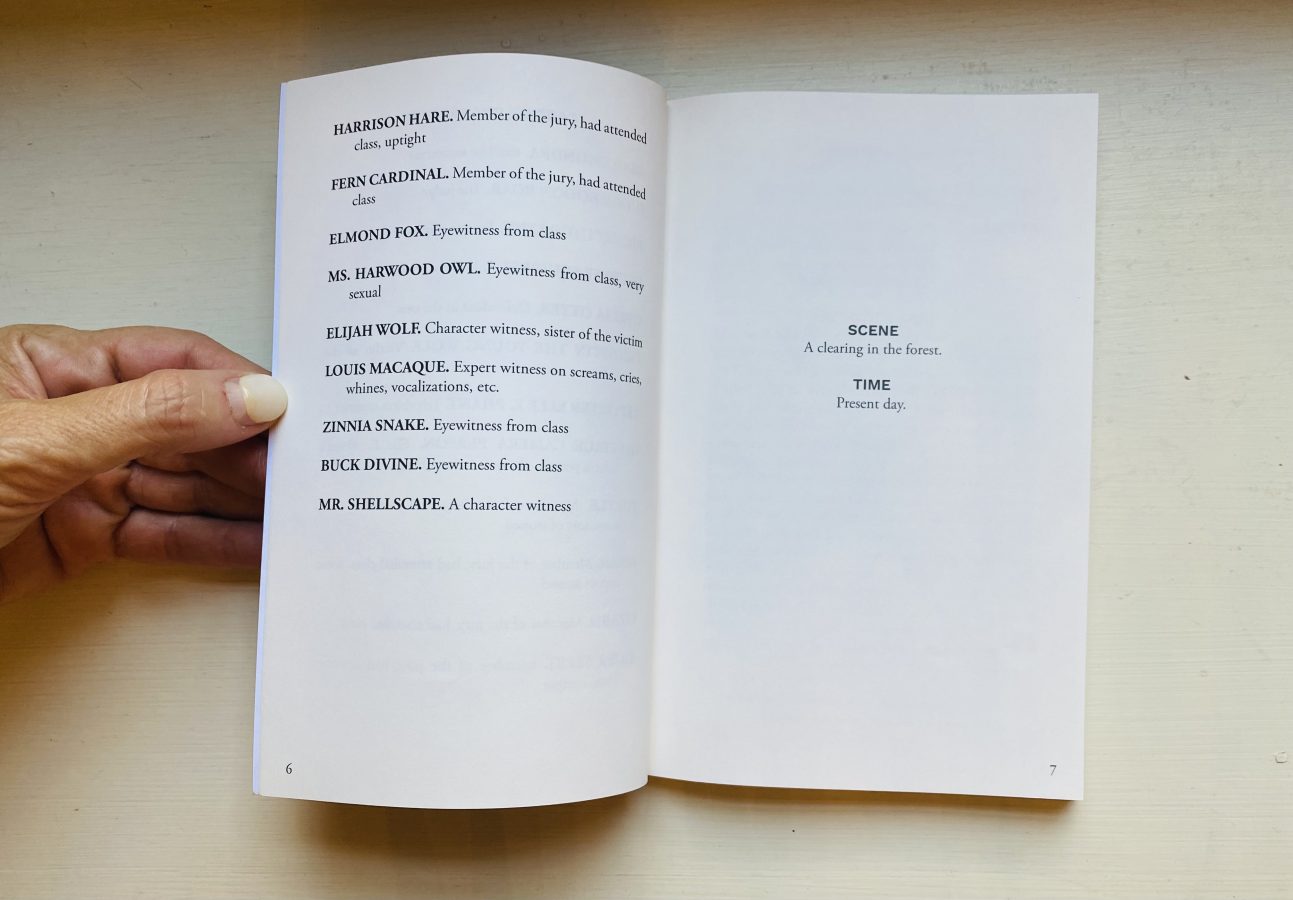

I’d like to know more about the process of choosing which animals you cast into the various roles. Not all of these animals (e.g., turtles, bison) tend to live in the woods. It seems to me that maybe some were chosen for linguistic reasons—like the pun of Elle E. Phant’s name, and the lovely melody of the word “macaque.” Some seem to be playing against type—you don’t often think of a bear as a fitness instructor, for instance. And it also seems important that there’s only one of each kind of animal, and so it comes off as a sort of cathexis of the myth of Noah’s Ark, Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, and The Muppet Show. Why these animals? And specifically, why do you think it’s an otter that kills a wolf?

Yes! Ha! So beautiful. So, yes, the pun of Elle E. Phant’s name. This was the name of my cousin Elysia’s favorite stuffed animal when we were children. Elysia was very particular when saying her name and it has stuck with me, the way we feel a word differently in our mouths and ears when we know its written mark—even if it might not really sound so very different. Elle E. Phant. And yes to the fantastic sound of “macaque” and their role in the play as an expert witness on screams, cries, whines, and vocalizations.

I think of Bear Chondra, who is the exercise instructor, as not really playing against type. I’m fascinated with the liminal place that bears exist in when hibernating. They don’t go entirely under when they’re hibernating, not as deeply as some other non-human animals. Bear Chondra’s monologue leading the Mix Flow Get Up and Go exercise class moves seamlessly from vanity to transcendence, firm buns to god, vulgarity to gentleness. There is an in-betweenness to the way she leads the class that feels like an echo of that half-hibernating. Maybe a lynx and a squirrel are both kind of “lawyerly” creatures? There is a speed and deliberation there that might be different from the sleepy stoned inference of a bison or turtle? And Zinnia the snake seems a bit expected—their winding, flexible language usage, their rejection of rules, like so many evolutionary queries tossed out by the snake communities every millennium! But it’s horribly fraught, isn’t it? Just how human animals use non-human animals as metaphors and lessons and models. As if these creatures were living on a separate plane from us, placed here to teach us lessons. I’m certainly not blameless in this.

One of the threads, or jokes, through the play is whether the humans are or are not on trial and how much the game of holding a trial is an appropriation of human animal proceedings not transferrable to “the woods.” To choose animals as characters separates human traits such as culture, age, class, nationality, race, and gender from the actions or ideas the non-human animals are playing with in the trial. It’s also an explicit comment on humanity, anthropocentrism, and the parallels between the intractable, untenable constraints of punitive justice and that whole concept of “getting to the truth” as a kind of fixed, visitable, or discoverable entity to the ways that humans view, commodify, use, and destroy non-human beings with impunity. Maybe this is a secret (fanatical) thread which is not as interesting to all readers, but I do think the humans, and the ways we’ve decided to organize our societies to the detriment of other flora and fauna, should be on trial.

Why an otter? That one is difficult . . . I mean, it’s not difficult to say, but I’m almost afraid to write it because I don’t want it to be a fixed critique or statement of my choice—the arrogance of a human animal judging a non-human animal—an embarrassing pitfall. Otters have a particular appeal to humans, don’t they? They are what we call “cute.” I am so so fascinated by the biological imperative “cute.” They are cute and they are very smart. Charismatic is a word humans like to use for animals like an otter. But they are also serial rapists and murderers and there is no denying it, and ethologists don’t really have any good theories as to why otters regularly display such unnecessary violence. But I don’t want you to think I am trying to take down the otter a notch, or that I chose that animal solely because of this tendency. I think they are also lovely and tender. I was attracted to this element of existence—that which can’t be understood. This is an obvious space that cannot be understood, certainly not by us. I think there is a deep kindness and wisdom in recognizing that most things cannot really be understood.

Mr. Shellscape describes seeing Ovelia Otter and her sister asleep holding paws which enrages Prosecutor Lynx—as if the sweetness of that gesture were an excuse for her senseless murder of Pennstin. Mr. Shellscape says:

We put things out there . . . we put visions and feelings and ideas into each other . . . some don’t stick around very long or make much of an impact at all and some reverberate. That floating trusting love I witnessed on my birthday was like a baptism or conversion or reading an important book. It impressed me and I brought its learning with me into the future. I know that what Ovelia Otter did at Bear Chondra’s Mix Flow Get Up And Go exercise class that day made an impression too. I know a lot of that fear and confusion and anger will pass through the woods for generations but I also know she put out some good too, and I guess I just wanted it to be balanced out a bit.

And maybe what I would most want for our penal system is a temporal expansion that just does not fit our speedy, productive society. How do we balance what a being has given to a community, a system, a time, a place? And how far back do we go to gather the metrics?

I’m interested that the act of violence happens in front of everyone’s eyes and seems to be unprovoked, and it seems like it would be a cut-and-dried court case, and yet it’s not. So many characters speak their various objections to the systems and the presuppositions of the trial itself, and yet they are engaging in it, but these aren’t exactly presented as didactic arguments for, say, abolition—but I also think it’s interesting that you don’t fall back on the trope of “oh, it’s just nature” because some of these creatures are predatory and carnivorous. The otter ends up refusing “forgiveness” and admitting not just to the murder, but to its sensuality.

I love what you’ve written here. Thank you. As far as forgiveness goes I think it is a much more valuable tool to give than to receive. I’m deeply moved by Frantz Fanon’s concept of radical forgiveness and if I even think (as I have just now) about the relatives of the Charleston Church shooting who gave their forgiveness to Dylann Roof I’m reduced to a puddle . . . but I also think I understand why Ovelia refuses forgiveness. I think maybe it’s too soon. She needs to hold onto that agent-regret. Too soon for her to drink that sweet draught.

I read an essay in the New Yorker about people who were accidental murderers—car accidents, etc. A few things were interesting about this—one was a reference to a “city of refuge” in Talmudic law where someone could go to be free of the families’ blood vengeance in the case of an accidental murder—which is profound, isn’t it? I mean, not the escaping a response but a place where one can go to sit with guilt and contemplate the enormity of fate. But the essay also cites a few philosophers and their arguments for expanding the “accidental” in accidental murder. What do we, and what do we not, have control over? What is exactly “accidental?” Having been born into poverty and violence like the young man who stabbed my next-door neighbors to death in a fit of madness? Having been born, as he was, to a mother and a father both of whom died before he was 13 due to drug addiction and violence? Is it an accident to have addiction, mental illness, rage, poor reasoning skills . . . I mean, the circle can go out and, again, I’m not legislating anything, I’m simply thinking about these things and don’t have clear answers but it would be foolish to consider blame without a great deal of dimensionality. And (forgive me) but what people call “nature” plays quite near to chance.