It’s no surprise that McCardell is popping up all over. Her design ethos of practical and comfortable clothes that respond to the wearer’s needs is as relevant as ever. The Frederick Art Club, founded in 1897 by a group of women artists, has framed their project to celebrate McCardell as part of a nationwide effort to, in the words of president Marilyn Bagel, “break the bronze ceiling.”

In terms of public sculpture, we’ve got plenty of allegorical women in the US, like Lady Liberty, but when it comes to celebrating the accomplishments of real women, they number only about 7 percent of public statues. The installation in Carroll Creek Park includes not only a stunning larger-than-life bronze sculpture of McCardell casually leaning on a dressmaker’s dummy by local artist Sarah Hempel Irani, but also a garden designed by Sharon Poole, inspired by the plaids McCardell loved to use, and interpretive signage designed by Irene Kiriloff. At the unveiling, speakers highlighted the uniqueness of this team of women who brought the project to fruition: both the artists and designers as well as those doing the fundraising.

At a moment when many are engaged in conversations about how we construct our public history, both in schools and in public space, it’s fascinating to see what new figures take on this monumental role. A fashion designer might not seem a likely choice in Frederick, and yet as I looked around at the crowd gathered in Carroll Creek Park for the statue’s unveiling, I could see her influence everywhere.

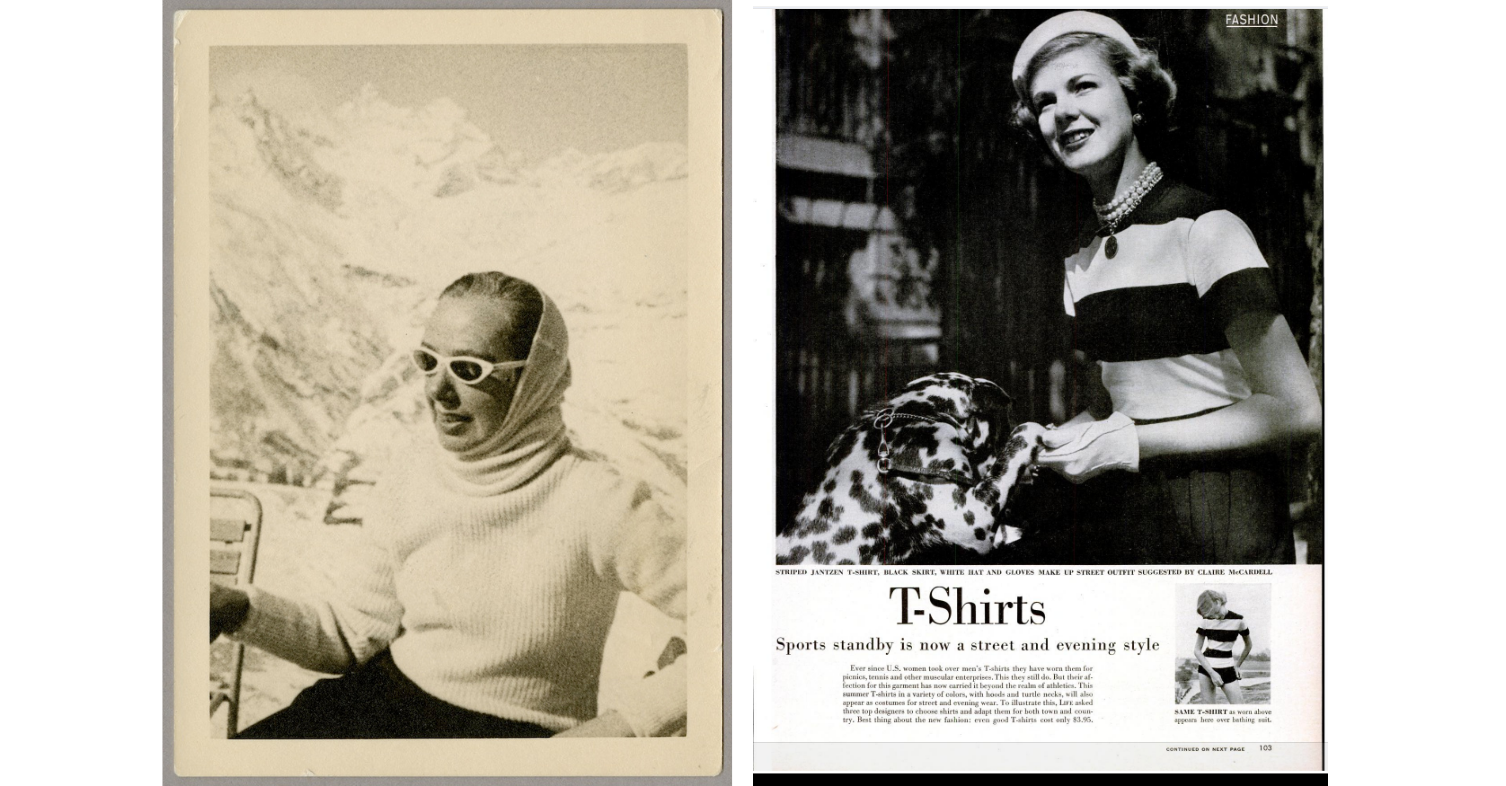

While only one or two people appeared to be wearing fashion knowingly inspired by the designer, I saw a number of styles that McCardell helped to popularize: trousers for women, leggings, ballet flats, and hoodies, to name just a few. As Bagel noted in her speech, Claire McCardell “changed the way women dressed.” The sculpture notably stands across the creek from the former Union Knitting Mills, a factory producing stockings and hose from 1880s until it closed in 1959. DuPont worked with the mill to test its newly invented material nylon in 1937, and the factory would be the first to manufacture nylon stockings, another revolution in women’s fashion.

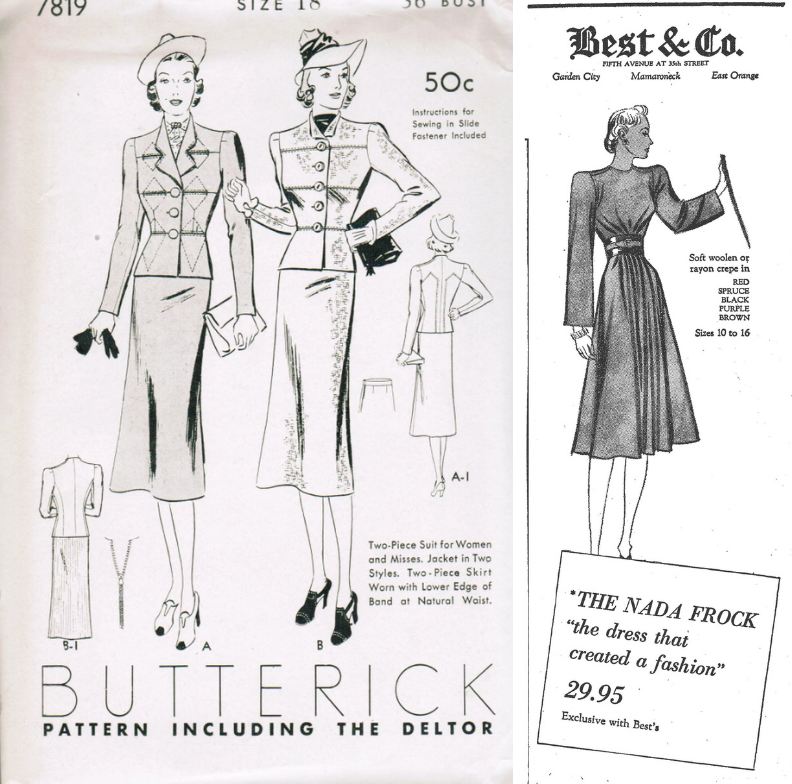

Irani’s bronze McCardell wears signature garments associated with the designer: a dirndl skirt with patch pockets and loosely tailored button-down top with a popped collar, accessorized with a slim belt, double strand of pearls, bangle bracelets, and ballet flats. The ensemble highlights some of the major contributions McCardell made to the development of a distinctly American way of dressing for women which focused on what was then called sportswear. While sportswear in the classic sense, for playing tennis or golf and lounging at the beach, had already been available as separate pieces, McCardell helped to move this idea into everyday dressing for women. She created pieces that could be mixed and matched, folded into a suitcase, and would look great when unpacked, eliminating the need for cumbersome trunks for travel and helping to push women’s fashion in a more casual direction. McCardell always insisted on practical pockets in her clothes, a detail that anyone buying women’s wear can tell you is still vanishingly rare. Irani also captured subtle details, such as topstitching and rolled cuffs used as decorative details.

McCardell favored practical embellishments rather than those that were added on and focused more attention on the beauty of the fabrics she chose. Visible hooks and eyes or buttons provided visual interest and topstitching could enhance the lines of a garment. McCardell also ensured that closures were in easy reach so women could dress themselves. In this way, McCardell was very much aligned with the Modernist movement in design that we now call mid-century modern. She created simple clothing that responded to the needs of modern life. She approached fashion from a problem-solving point of view. Curator Bernard Rudofsky of The Museum of Modern Art even deigned to include her among the very few contemporary designers represented in the 1947 exhibition Are Clothes Modern? Rudofsky answered the question with an emphatic “No!” in relation to most European and American designs, which he viewed as irrational, but he celebrated the logic and geometry of McCardell’s draping, as well as her mindful usage of materials.