There’s even more to the work than that: We can also open a birdhouse to reveal a cluster of small items evoking Martin’s life—and trigger, in the process, recordings of a Bachman’s warbler, an extremely rare songbird. Cumulatively, these disparate elements suggest a fugitive quality, hinting at the obscured beauty of a native bird and the work of overlooked laborers. It’s a potent, haunting, and deeply thoughtful work, although it may go too far as a corrective. While the zine quotes a number of passages in Lindsay’s book, it makes no mention of several key assertions on the book’s first page. I’m thinking, for instance, of Lindsay’s observation that “Maria Martin was acknowledged more frequently than any of Audubon’s other assistants,” and the scholar’s claim that “modern sensibilities behind suggestions that she had aspirations as an artist or that she sought personal acclaim were antithetical to the ideals that shaped her: evangelical Lutheranism and Southern culture.” In baldly ignoring these fundamental passages, the zine feels less than fully responsible, weakening the work’s otherwise absorbing attention to complexity.

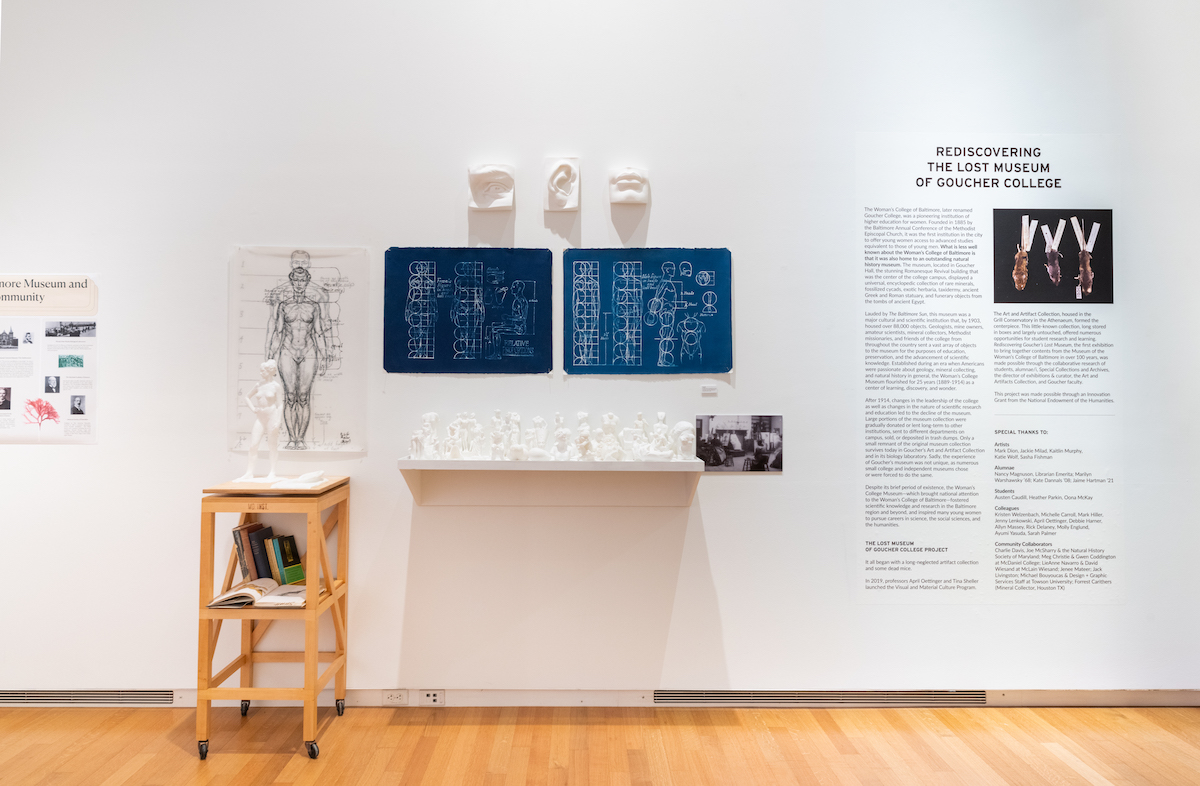

After passing through a small room that evokes what was once a sizable subcollection of lantern slides picturing specimens and architectural forms, we find ourselves before several shelves carrying some of the myriad items that once comprised the collection. Viewers familiar with the Walters Art Museum’s recreation of a chamber of wonders will have a sense of the wild variety of forms and surfaces that co-exist here: mounted beetles, pressed leaves, and posed chimpanzee skeletons all share space. Collectively, they evoke the sense of wonder and insatiable curiosity that often underlay natural theology and the formation of so-called encyclopedic collections.

Nominally, Wunderkammern suggested a process of ordering and an implicit mastery of a complex world. (In such collections, Francis Bacon once observed, “whatsoever […] singularity, chance and the shuffle of things has produced […] shall be sorted and included.”) But the limits of such an approach were also apparent at an early date. Galileo wrote of “curious little men” who delighted in collecting “a petrified crab, a desiccated chameleon, a fly or spider in gelatin or amber, those small clay figurines, supposedly found in ancient Egyptian burial chambers…” Arrayed according to logics that can feel haphazard, such assemblies can border on the random and even the ludicrous.

Galileo would likely have nodded in unsurprised recognition at an adjacent display of Mesoamerican artifacts: the products of sophisticated cultures cheek by jowl with a cat’s pulmonary system. But the show has a more sophisticated point in mind, as the next few displays center on some of the complex ways in which other cultures were represented in the Goucher collection. Four watercolors of Native Americans by Frank Blackwell Mayer, originally executed in pen and pencil, reflect an inquisitive, sensitive observational skill: a quality also evident in Mayer’s journal entries from the time. A series of silhouettes refers to 18 artifacts that, when unboxed, turned out to be likely grave goods—and thus subject to federal policies. The school is engaged in an ongoing effort to understand the history of the works and to repatriate them where appropriate.

Equally complex factors also inform the show’s treatment of Egyptian antiquities. In 1895, John Franklin Goucher traveled to Egypt and, like many wealthy patrons of the time, purchased a mummy. That mummy eventually made its way into the Johns Hopkins University Archaeological Museum, where it was displayed and subjected to various processes of scientific imaging. As ethical standards surrounding the display of the remains of the dead have evolved, though, such practices have come to feel inappropriate, and JHU has thus removed the mummy and related photographs from display.

Here, a wall text rehearses that history, and three large hangings by the artist Jackie Milad gesture, in busy layered collages of color, pattern, text, and ancient Egyptian forms, at these complicated overlaid histories. It’s worth noting that Milad is both Egyptian and Honduran, and that her practice links ancient images and symbols with contemporary languages and popular culture. In this context, Milad’s work questions the meanings of historic objects and complicates their legacy, suggesting visual and conceptual relationships between ancient objects and contemporary art, where meaning is constructed and hidden in symbolic hierarchies.

Finally, the last installations reiterate the importance of Goucher and Bibbins and allude to the way in which the collection formed a part of their quotidian world. An elaborate set offers yet another creative reframing of the material, integrating objects from the collection into a comfortable period interior. Wall texts emphasize Bibbins’ accomplishments as a teacher and a leader and his deep respect for Goucher and his “life-long love of nature.” The diverse show, having employed a wide range of narrative and exhibitionary strategies in telling an intricate history, ends more or less as it began, by positioning the Goucher museum as a sizable resource formed “for the purposes of education, preservation, and the advancement of scientific knowledge.”