BmoreArt: Your title at the Walters is Curator of the Americas. What exactly does this mean in terms of geography and history?

Ellen Hoobler: We have often wondered what we should call this curatorial position! Some possibilities are curator of Art of the ANCIENT Americas—but the collection I oversee includes examples from the colonial period, and even into the 19th century; or Art of the INDIGENOUS Americas. Since my collection includes our few Native American works, that seems most appropriate, but again, as the collection encompasses works from colonial Latin America that were used and perhaps even made by people of a mestizo, or mixed racial background, that is not quite accurate either.

So we have settled on “Art of the Americas,” which I like because it reminds people that although many people in the US call themselves Americans, the continent we inhabit includes people of many other nationalities as well, who are also Americans. However, most of the artworks that I curate are from North, Central, and South America, ranging from Mexico to Peru, and date from as early as about 2000 BCE until the Spanish invasion ca. 1520.

What’s your professional and educational background that led you to this point in your career?

I studied Latin American Studies in college, worked at the auction houses in New York briefly, had a stint with Latin American clients in private banking, and also used to run a small company that offered tours focused on folk and fine art in Oaxaca, Mexico. But eventually I went back to graduate school to focus on ancient art of the Americas. During grad school, I had the opportunity to study the Zapotec language of Oaxaca for three summers and then to live in Mexico City for two years to conduct archival research. I have also traveled to Guatemala, Belize, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Ecuador, and hope to travel again as the pandemic begins to ease.

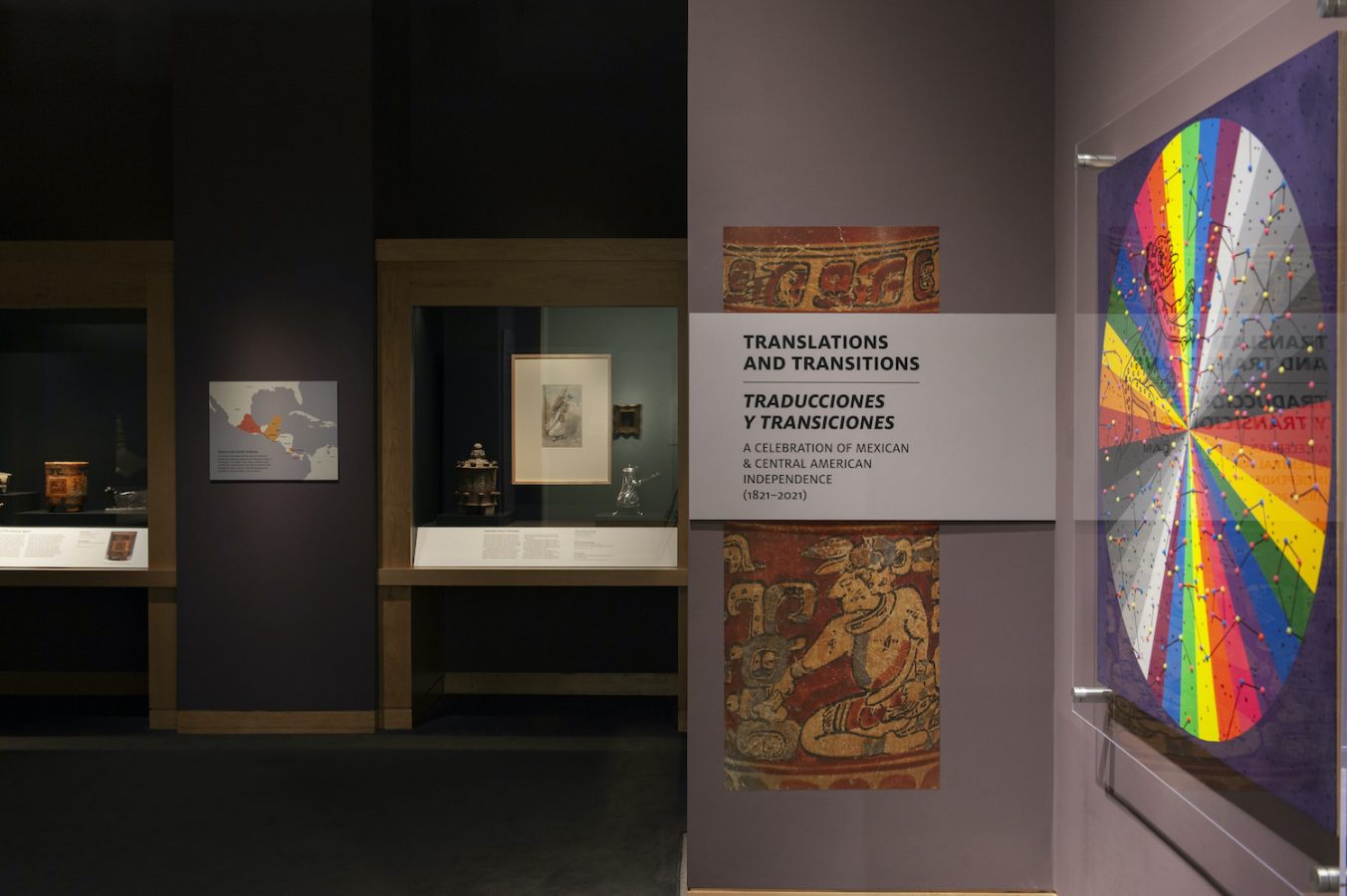

The goal for this “small but mighty” exhibition is to celebrate the rich cultures of Mexico and Central America—including Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. Given Baltimore’s most recent census data showing that the Latino population is our fastest growing segment, Traducciones Y Transiciones seems like a perfect opportunity to reach out to Baltimore’s immigrant community and reflect a shared history, specifically around independence from Spanish domination. Can you talk generally about this exhibit and how it is a moment to learn more about history and culture—as Americans and as immigrants?

This exhibition was a great opportunity for the Walters to show a commitment to presenting the histories of different peoples in our local community, in this case to show an aspect of Latin American history. Preparations for the show included working with our amazing Adult Programs Team to plan a lot of virtual programming from many perspectives—how complex the idea of heritage is in Mexico, the challenges and joys of teaching Mayan languages in Guatemala, how mapping makes tangible the experiences of Native American and Black communities in Maryland—which supported the exhibition but also are available for the future on our social media channels.

How do you ensure that immigrant populations and non-English speakers can access the exhibit?

We tried to make the show fully accessible to different people by offering Spanish-language versions of the labels, so families with a range of language preferences could all feel comfortable with it.

I see the show as one form of reaching out to the Latino/a or Latinx population in the city and region, and it’s part of a larger initiative we’re undertaking as we begin preparations for a broader installation of the Latin American collection, due to open in 2024. We’re forming a community advisory group, and to undertake focus groups to understand what people would want to see in a larger exhibition.

However, this exhibition is not happening in isolation. In 2018 and 2019, we also put on two other small shows, Crowning Glory and Transformation, which showed us that there was a hunger for more exhibitions of works from these areas.

I remember particularly a time when we had a group of students from the Wolfe Street Academy, and the docent touring them through the show said that when they came into the exhibition, they immediately congregated in front of the exhibition’s map, showing Latin America, and proudly pointed out to her the countries where their families had come from. There were comments like, “Mi abuela es de allí!” (My grandmother is from there!) That showed this was personally important to our public. The works in that show, and others we undertake, will of course mean different things to different people—some will see artistic inspiration for their own works, others experience objects of curiosity, or of sublime beauty that uplift their everyday experience. But some people will experience belonging within the community by seeing their own ancestral traditions reflected in the space of the museum, and that’s really important for me.

Although a struggle for independence occurred over centuries, Mexico and Central America won their freedom back from Spain officially in 1821, which is the year designated to commemorate independence. After self-governing nations were established, a new appreciation emerged for indigenous culture and knowledge as well. Can you talk about the six major themes that organize the show and how you have organized the objects to present a story about Indigenous roots, Spanish influence, and eventual independence from the conquistadors?

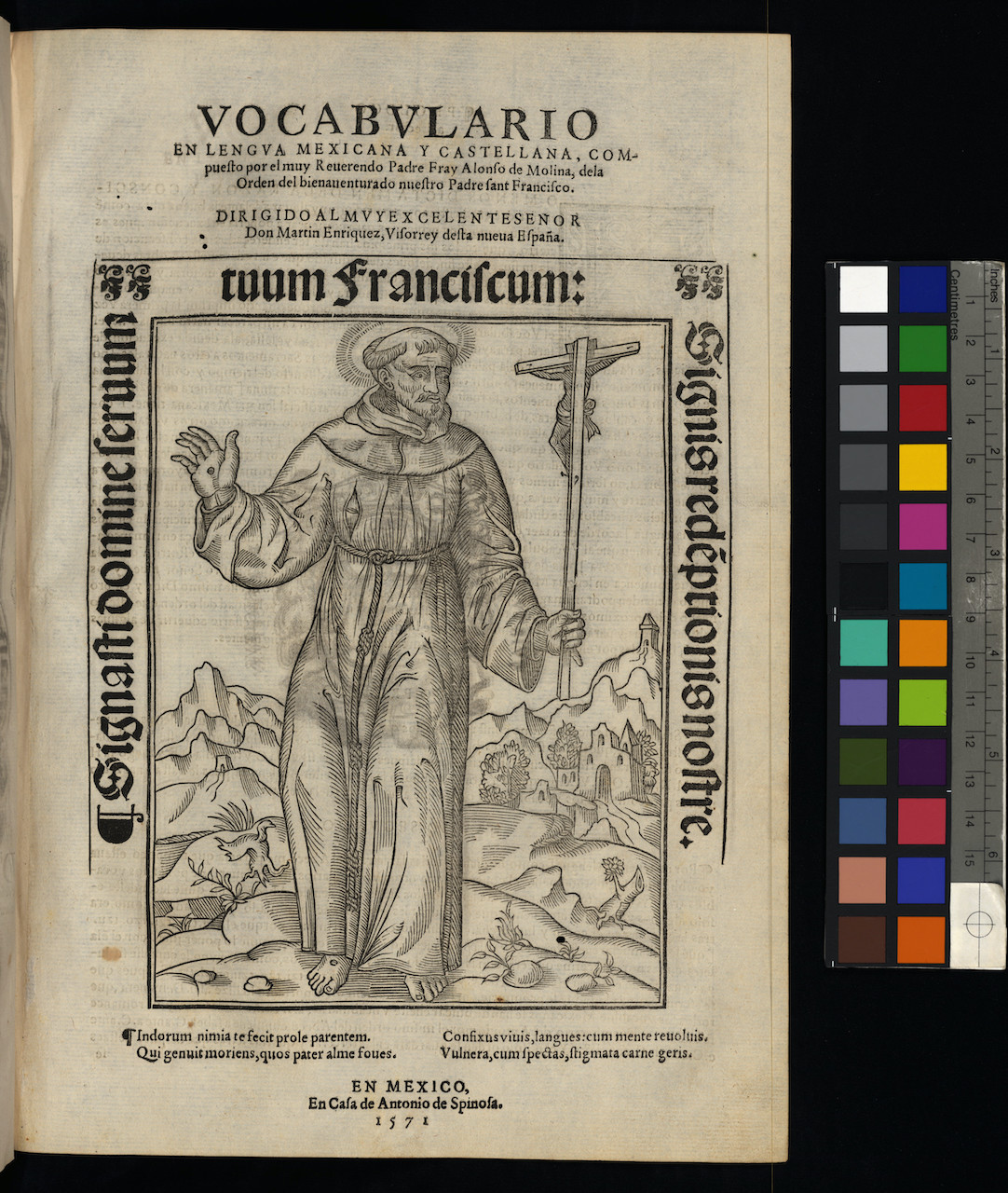

The show is organized around six forms of Indigenous knowledge: 1.) Indigenous languages; 2.) foodways, specifically use of chocolate; 3.) forms of mapping the physical environment; 4.) knowledge of animals, especially jaguars; 5.) deities and belief systems; and 6.) mastery of astronomy.

The exhibition explores how those inventions, worldviews, or shared understandings were created during ancient times, developed over hundreds or thousands of years, and then were radically transformed after the Spanish invasion of the Americas circa 1500. In some cases, European conquistadors tried to suppress these ways of knowing, or to radically transform them for new purposes, but they survived and evolved during about three centuries of colonization, and have continued to endure (and in some cases to thrive) since independence from Spain in 1821.