Something I was hearing in a couple of the interviews that I listened to was the attitude that you can’t be apathetic. In one interview, a woman was noting how these days everyone is isolated and individualistic, and although there are people helping their communities and trying to affect change, we always need more. Also, I stumbled across something the police/prison abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba said on Twitter today, I’m just gonna read it to you: “Been thinking a lot lately about people who say that they despair because they can’t single-handedly save the world. There’s a strange thing that I notice particularly in the U.S. where some people think that they have to take heroic action or no action at all.” She goes on to say that her friends and comrades hear this all the time, but you have to recognize that everyone’s in a position to do something. You just have to take steps towards the thing, and it’s a collective struggle. That is an important, subtle thing that comes through in this project—the connections amongst a lot of women’s work here, and the ways that no singular one thing, or singular person, is going to turn a whole thing around.

Whitney Frazier: One of my white friends who came to the show, who lives in Pikesville, her reflection was like, “wow, I need to do more, I need to be in service to my own community.” She’s like, “these women are doing so much, and I look at my life, and I’m like, what am I doing?” I know “service” can be a word that people don’t like to use, but be in service to something or someone outside of your everyday life, like, okay, I take care of my kids, I go to work, I do this thing. Even the smallest thing in your own community can make a change.

With my background in organizing, what I’ve learned is that focusing locally is really important, for me, to see small changes happen. Having a rec center be rebuilt, it’s really empowering to be like, “I helped make that thing happen.” Something that many of the women have seen happen is their efforts, as small as they are sometimes, make those changes in their immediate community and improve people’s lives. It’s overwhelming, and kind of a defeatist attitude—and not really the right way to think—to think that you need to change the world.

It’s interesting, too, because Baltimore is a hard place to live for a lot of people, but when something like The Wire is presenting the city a certain way to a broad audience, then it becomes a symbol for the whole place to people who don’t actually know the place.

Kirby Griffin: I mean, some of what The Wire shows is a real thing that is a part of the city, but that is a part of every city in America. The problem is the lack of balance. We don’t see the other sides, we just get The Wire. And through the power of media—we all have a thing subconsciously, that whatever we see on the TV, we kind of take as real life. Granted, you grow out of it, but you can’t shake the idea that when you were young, when you were a child, you thought things on TV were real. So you’ve got to spend another X-amount of years of your life trying to undo the idea.

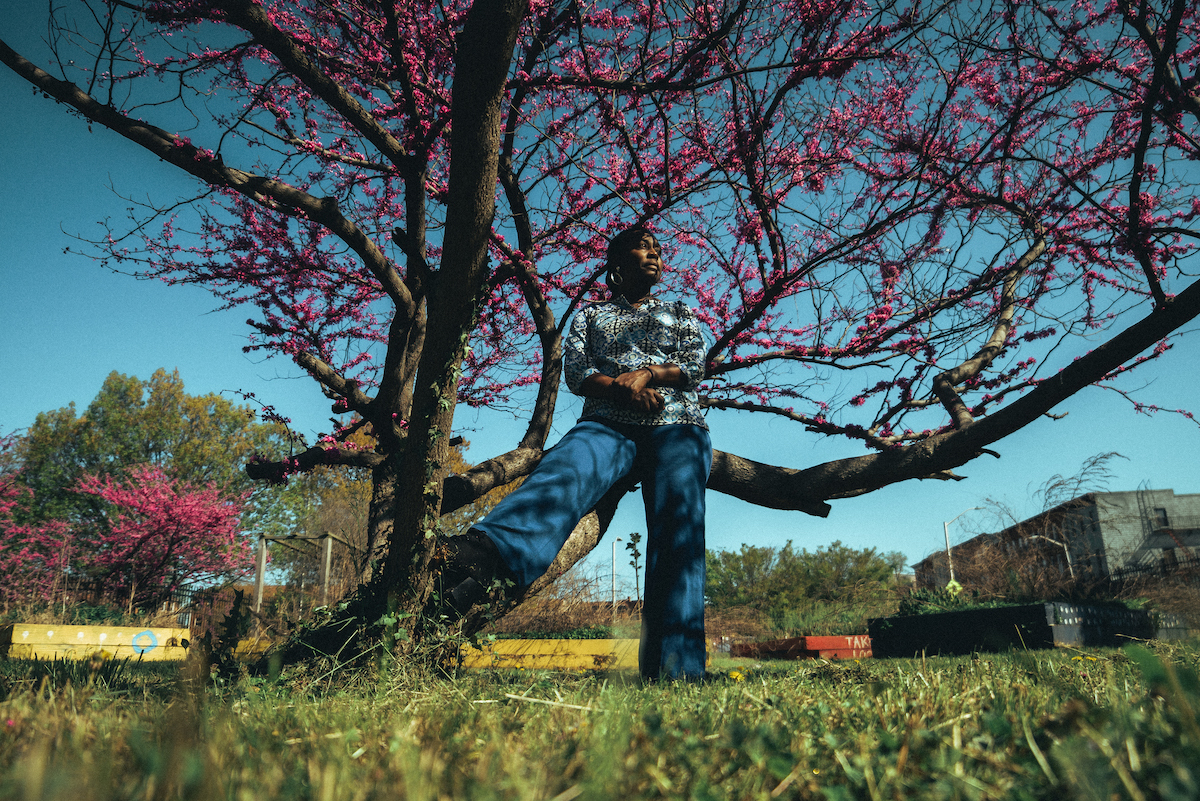

Whitney Frazier: When Audrey [Carter]’s kids saw her on City Hall, it’s like the shift that you’re talking about, Kirby. We are so used to seeing something negative or violence glorified in the media. But now we’re looking at someone who is doing good work, who’s been lifted up and put on that platform.

Kirby Griffin: Right now, we don’t see that. That hasn’t been a “cool” thing. Anytime something is blasted out there on the public level, it’s like, what happened? In these environments, the only time somebody ends up on a T-shirt or on a wall is when they’re dead. So to put somebody or to put multiple people up on the wall and put them up on a pedestal for something positive, for something that they are still currently doing, it’s not seen too much. And that has to become the norm at some point.

Listening to some of the women’s stories, I found myself thinking of other people doing similar work, and also found myself wanting even more details about the women and what they do. I was also surprised that policing is, in a way, part of this project. The Baltimore Police Department is notoriously corrupt. Can you tell me about what it was like to include Deputy Commissioner Sheree Briscoe in this project?

Whitney Frazier: We talked about this, Kirby, at some point, before the photo shoot or after the photo shoot. For me, she is trying to change the institution. She’s a fighter, she’s on the inside doing really good work. And it’s amazing, being in her presence and how humble she was and is and how relational she is with all the others—she doesn’t see herself as separate or different or above, I’ll just say that much. I understand all of the tension of how it might have been viewed to include a police officer, but that’s what we’re talking about—we’ve got to show the good with the bad, we’ve got to show people doing good work.

Kirby Griffin: When I see police officers involved in anything, I’m always just like, “who invited them?” if I’m being honest, just because of my relationship in my neighborhood with law enforcement. But it’s necessary [to include her] because, essentially, she represents an organization that has failed to do everything that the Guardians are trying to do right now, if we want to be completely transparent about it. With that being said, law enforcement is necessary and it has to be here—at least until we get to a point that we can police our own communities. So she represents someone who is trying to [effect change] on a grander scale, because you can’t always do everything on the street level. You need that part as well, but then you do need somebody who has more resources behind them that can actually make things happen.

Granted, she can’t do it by herself, that’s impossible. But that she’s trying, that is enough, and her husband is involved, and her husband is with her, so that’s saying a lot. She represents what law enforcement could be, what it should be in so many ways. I think it brings it full circle because everything that our Guardians are trying to combat in their communities are things that law enforcement should be trying to do, day in and day out, but has proved time and time again, that’s just not the case. So we do need somebody involved on that side as well.

Whitney Frazier: One thing that would be powerful moving forward, is how do the Guardians interact with younger Guardians or a younger generation? You have to work, you have to get a seat at the table, you’ve got to work with people like Sheree Briscoe, you’ve got to work with Mayor Scott, you’ve got to work with people in these positions if you really, in my opinion, want to get things done. What I’ve learned and observed is, if you want to be at the table to be making real change, you’ve got to learn how to negotiate and work at different levels and with different leaders and different institutions. And I want the younger generation to learn from the Guardians about some of that work.