From manipulated found object sculptures to cotton cyanotypes, oil paintings, and collages, the material choices and styles vary widely among the six Mid-Atlantic artists selected for the Arlington Arts Center’s Solos 2022 Exhibition. The artists—Kyrae Dawaun, Danni O’Brien, Alexander D’Agostino, Sharon Shapiro, Marisa Stratton, and Ju Yun—each have an investigative approach to art-making and present new, invigorating works in their solo shows.

In Cursing the Very God (…), Kyrae Dawaun offers fragments of his dissection of belief structures through six oil paintings and two mixed-media sculptures. Intimate moments between individuals, movie snapshots, and plant still lives suggest building blocks of ideology. Religion and the entertainment industry are larger webs that weave through our everyday, subconsciously instilling social norms; they are intriguing source material to deconstruct because of their ubiquitous, pacifying and narrative nature.

In “Follow Him (after her)” (2022) Dawaun references the 1992 comedy Sister Act, starring Whoopi Goldberg, who plays a singer disguised as a nun as part of a witness protection program. In the painting’s foreground, a yellow undertone wash divides two figures: Sister Mary Robert (Wendy Makkena) and Deloris (Goldberg) are caught in a cathartic moment of singing. The scene feels loud and visceral, evoking a breakthrough.

The intensity of the characters contrasts with the other paintings that feel more somber, such as “Francis as Snow” (2022), a painting of a man lying on the sidewalk with two pigeons in front of him. Or “Pitched Hands” (2022), an image of gloved hands gathered in a pleading gesture, hung above eye level.

The figurative paintings are accompanied by two sculptures. “Limp Edifice [to be inspired]” (2022) is a copper-tinted gypsum form on top of pine furniture, which resembles a toy ironing board with a satin-finish cover. The geometric shape can be read as many things at once: something phallic, an alien-like statue, an ordinary domestic object that alludes to the home, where many of our belief systems are formed. Punctuated with religious symbols, Dawaun’s works form an ironic tension with the show’s title which suggests a denunciation of God. Perhaps the fragments act as a spiritual re-learning of a largely colonial structure on the artist’s own terms.

I follow a low hum to the partition wall and beyond it, into Danni O’Brien’s show, Glow Up, where I meet plastic detritus turned into elaborate, eerie, light objects. Most are monochromatic with geometric soft forms that I want to touch. I navigate first toward “Dips & Snack Diaphragm” (2022). Its allure is magnetic, and its shape resembles an altar or cloister arch. Its paper pulp skin or membrane is a soft peach orange with a red step-by-step diagram string line drawing of cups and a hand. Above this drawing is an inset circular plastic object, a chip-and-dip bowl that glows warm yellow.

The texture and colors are reminiscent of a body, and what I thought at first was a menstrual cup turned out to be a diaphragm, the dome-shaped silicone contraceptive device. The play with the shapes and names is humorous, but also strange, as something very private is brought into a public setting and juxtaposed with eating. In a tongue-in-cheek manner, it points to what we desire and consume. The extension cord, the same orange, swivels to the ground and into the wall. This piece, like many of the others, pulls the viewer in with its exciting tactility and sound.

While most of O’Brien’s sculptures have light, sound, or video components, “A Poke, A Prod, A Carrot, A Nod” (2021) does not. The three-foot-tall sculpture is assembled from coat racks, jewelry organizers, found ceramic carrots, a bike seat, hand-built ceramics, a flickering candle night light, and paper pulp. The many-legged creature reminds me of octopuses with tentacles feeling their way through space, mapping reality. In O’Brien’s work, found objects are manipulated, combined, and reimagined into soft alien structures pointing to the potential of the objects surrounding us and their fate once they become debris.

Similarly, there is a specific yet subdued aura within Alexander D’Agostino’s Lavender Shrine. Working with cyanotypes and archival material, he explores the Lavender Scare, a Cold War-era period when the federal government harassed and discriminated against LGBTQ employees, effectively institutionalizing homophobia.

Dried lavender lines the ground on the left underneath “Queer Shroud Grid: Lavender Scare” (2022), a collection of 124 small (about 8.5-x-11 inch) cyanotypes with solar-fast dye on cotton. The images read like flashbacks, or partially erased memories, as they appear damaged and burned. Protests, medieval drawings, homophobic propaganda, caterpillars, and butterflies are depicted among the shroud grid, which ranges in color from soft pink to vivid indigo. Some imagery repeats, creating an overwhelming sense of a collaged struggle.

Central to the room is “Queer Shroud Grimoires” (2022), three leather-bound books also comprising shrouds resting on wooden holders, with three pink candles in front. Six gold hexagonal mirrors are placed under each object, creating a futuristic effect and alluding to parts of the James Webb telescope, which D’Agostino also references in another sculpture to scrutinize Webb’s involvement in the Lavender Scare. In early 2021, several astronomers at NASA voiced their discontent about the telescope’s name due to discrimination at the agency under Webb’s leadership.

Above the books is a large cyanotype of the Tiffany window, originally part of the Abbey Mausoleum, from the Arlington Arts Center’s performance room. D’Agostino purposefully defines and contextualizes his objects in spiritual mysticism: a grimoire is also known as a book of spells, while a shroud is a garment that is wrapped around a deceased person for burial. I find myself kneeling in front of grimoires to observe the imagery and am enveloped in the smell of lavender. The collection and presentation of these objects feel like an act of remembrance and processing of vicious historical acts.

Through large-scale collages, Sharon Shapiro in Then the Dream Changed also crafts commentary on historical structures, injustices, and the way the past is still shaping the present. She uses found and sourced imagery of American leisurely home life juxtaposed with protests and social upheavals.

In “Window Dressing” (2022), a white woman is sprawled on a sofa within a luxurious interior, underneath a painting that resembles Joan Miró’s work. Behind her are Cubist still lives, and through the large window we see a gathering of discontented Black folks; the source of that image looks like it could be from a Civil Rights-era demonstration. The unaware woman’s solitary form occupies the large, curated, modernist space, which contrasts with the densely packed outdoors. Questions of what spaces are kept and taken care of; who can afford to take care of these spaces; who has a right to exist or relax in a certain space all come to my mind.

Shapiro uses imagery to discuss power and privilege in other collages too. In “Made in America” (2022), a white woman whose clothes suggest the 1960s is sitting on a tree trunk looking at a Black woman wrapped in the US flag standing atop another tree trunk, which almost acts as a pedestal. The spatial relationship of the two conjures uncomfortable images of the slave trade and its legacy of institutional racism. The white woman’s stare feels objectifying. The title suggests a manufacturing of sorts, which makes me wonder what was and is being made here.

The large blown-up collages, each measuring 60 x 55 inches, augment the discomfort they instill in the viewer. History cannot be repeated and for society to develop, the past must be faced and atoned. Shapiro’s narrative collages present class and race issues, questioning who has access, power, and privilege.

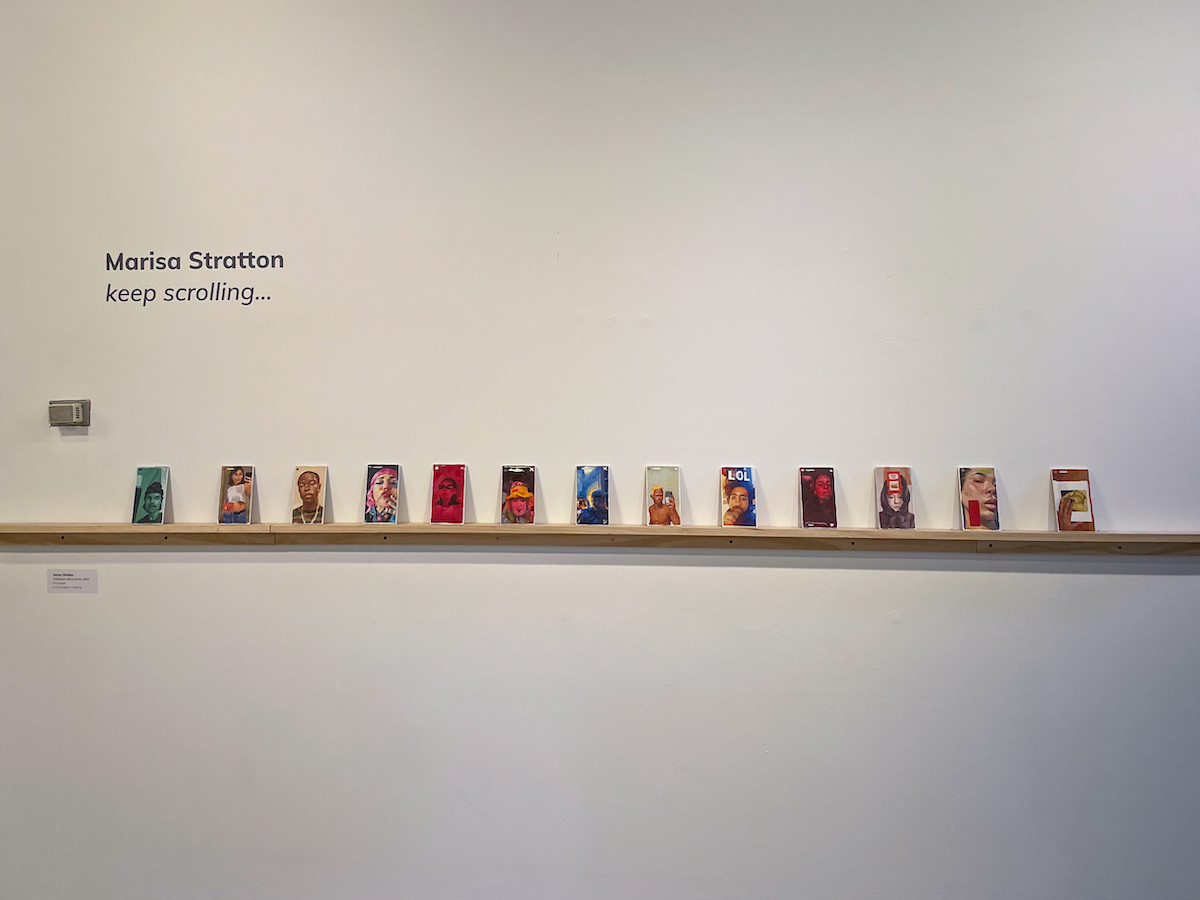

Marisa Stratton in keep scrolling… also presents figurative work, however more intimately as portraiture. Her sources are Instagram stories of everyday individuals she follows, grounding the works in the present. The paintings feel like an accumulation, as if the viewer was scrolling through the artist’s social media account. We live our lives through a conglomeration of images both through the physical and the digital. Our smartphone photos folder and our social media accounts are small bits of curated digital self-portraits. Here, the paintings are small, reflecting the digital handheld doorway. And Stratton acknowledges her models by titling each work with the users’ handles.

Stratton’s brushstrokes are luscious, with a soft haze, completely different from, yet reminiscent of, the glow of the screen. The source images are ephemeral snapshots of these users’ lives, but they are archived now in the traditional medium of oil paint. They feel sensual, capturing faces in their homes and cars. On the smaller wall section, I enjoy the combination of “@erinyahi” (2020), a woman in a black hoodie with an Instagram filter, followed by “@theoriginalmalia” (2020) an up-close view of a woman’s face, followed by “@m__a__y_a” (2020) of a woman’s hand holding a book open to Gustave Courbet’s “L’Origine du Monde (The Origin of the World).”

Most of Stratton’s paintings are on wooden panels, layered horizontally in a row. Other paintings are arranged into octagonal and square forms, with the images painted on the inside or the outside. The mundaneness of the subject matter highlights the beauty in the everyday and elevates the Instagram story to a higher status. The posted stories are ephemeral self-portraits that only live for 24 hours online; thus Stratton’s project is an act of preservation.

Explorative portraiture is also visible in Ju Yun’s East Meets West, a show of sculptural wall reliefs and paintings. Yun dissects and reassembles cultural symbols from South Korea and the United States to delve into nostalgia, home, and identity with material play.

In “Imaginary Friends” (2020), she is inspired by traditional dance masks, but uses unconventional building materials such as polymer clay, large plastic eyes, synthetic fabric, and insulation foam. The vibrant reds and purples add playfulness to these large faces, and the plastic detritus of found objects in both cultures grounds it in a current moment. The anthropomorphized characters are spirited and very tactile, their insulation foam noses with beads are alluring. This sense of play and exploration stretches over to other works.

The collaged relief sculptures of plastic toys, objects and painted parts point at our consumerist culture that endlessly collects. The reliefs are mostly borderless, amalgamating on the wall like clouds. In “Welcome Home” (2021), I come face to face with a blue and white collaged abstract landscape. It feels whimsical and otherworldly. Yun combines multiple textures to create this fragmented fluid dreamscape. On the left and right sides are soft white felted objects resembling clouds. The center is occupied by flowing synthetic hair that reminds me of toy unicorns from my childhood, hanging purple and blue beads, and an oil painting of waves and curvy, soft, mountain-like forms.

The combination of natural imagery created from plastic toys and objects leaves me with the thought of what we collect and leave behind. Our objects capture stories and thus hold memories of different times and places. This imbued nostalgic power is often rose-tainted, but nonetheless a building block of who we have become.

*****

The shows opened on May 15 and will be on view until June 18.