Evan Woodard knows his shit. A Washington, DC, native, historian, and board member of the Baltimore Antique Bottle Club, Woodard is interested in the history of the objects he and his friends find in the Baltimore privies they dig up. Baltimore, a city established well before indoor plumbing, has a density of pre-Civil-War-era working-class houses. Many have small backyards where, in a back corner farthest from the building, a person armed mostly with hardware-store equipment can uncover a portal that leads directly to the literal refuse of the past.

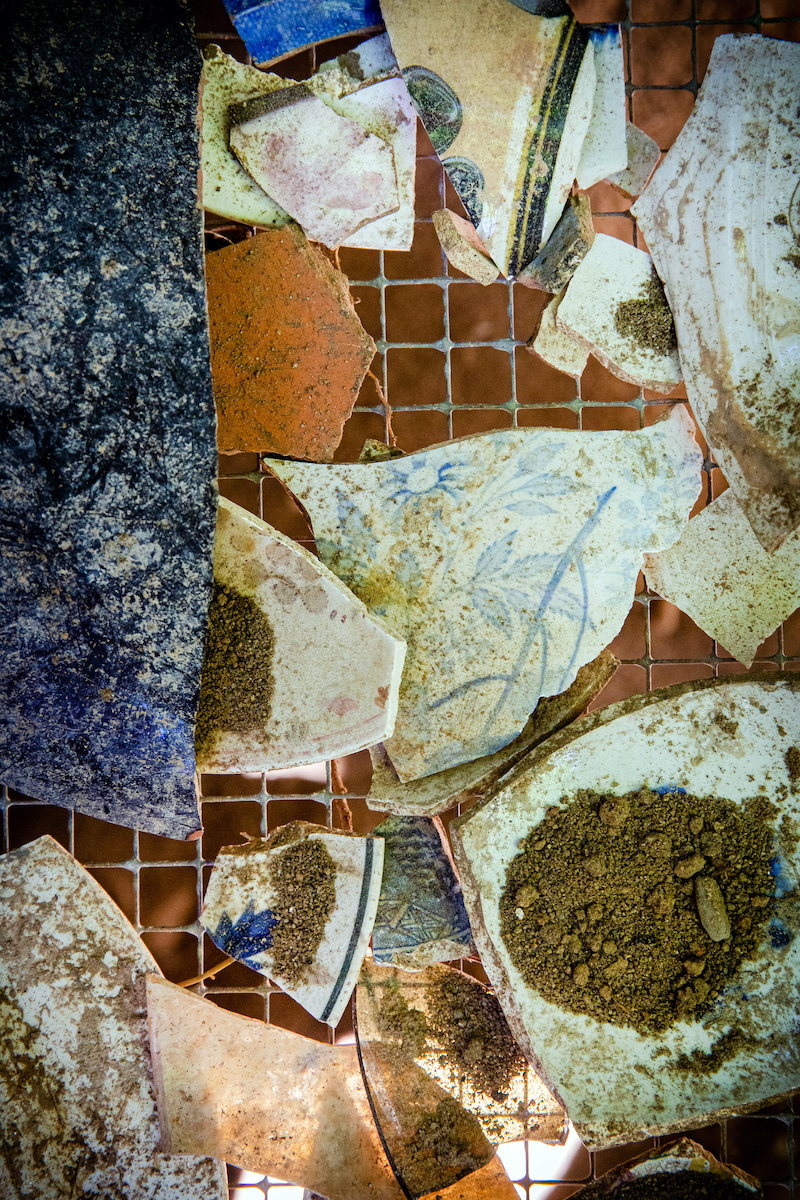

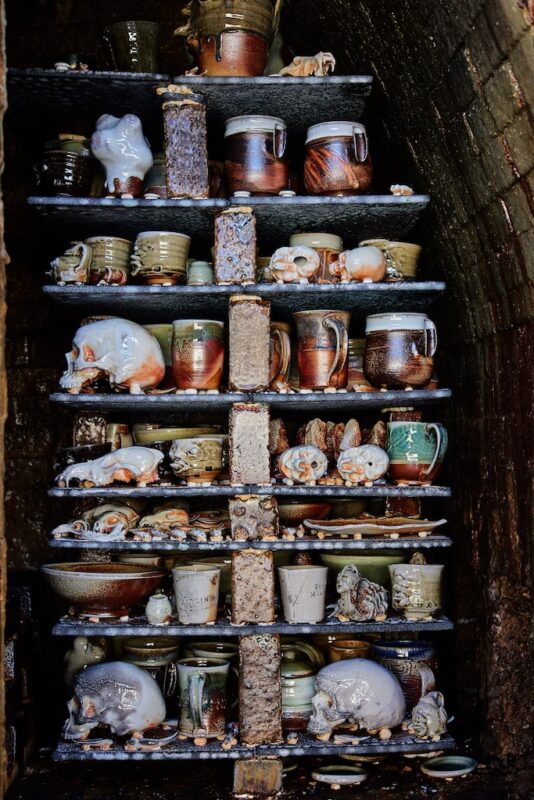

Woodard got into digging up strangers’ backyards after his friend, Matt Palmer, discovered some old bottles while hiking early in the pandemic. Internet research led Woodard and Palmer to the concept of privy digging, which seemed to promise more old bottles than the woods. They haven’t stopped since. Woodard estimates that his crew—Palmer, Chris Roswell, Phil Edmonds, and Ryan McCloskey—known as Salvage Arc, dug about 115 or 120 sites, finding all manner of treasure and very old trash. There’s an element of gambling to privy digging—Woodard and his friends have dug 20-foot holes only to find that the privy had already been emptied and thus come up with nothing.

While this method of discovery is relatively new to Woodard, his interest in history originated in childhood. After high school, he attended a semester at Bowie State but decided college wasn’t for him and started a career in photography, taking images of abandoned spaces and then commercial real estate photography as a source of income. He recognizes the throughline to what he is doing now because he has always been interested in the story of cities, their structures, and the people that came before.

He’s trying to take privy-digging, and more broadly his brand of interpretive history, worldwide. Woodard believes the best way to teach others about the past is to reconstruct the narratives that connect the past with the present based on the lives of real people. On his Instagram (@salvagearc), drawing upon ship manifests, census records, and other primary documents, Woodard uses the captions to educate. A self-taught researcher, Woodard is interested in uncovering stories of the objects he finds and sharing them broadly. He wants his audience to know the stories behind the things he finds, getting as specific as, “Who owned this bottle? Or who manufactured it? What was their story? How did they get to America?”