Yam Chew Oh is very easy to talk to. So easy to talk to, in fact, that over the course of our two-hour-plus conversation, I had to keep reminding myself that my sole purpose in his light-filled home studio was not to eat the spread of snacks he had thoughtfully prepared and then fall in love with Roger, his human-food-obsessed rescue beagle—my goal was to learn more about Oh’s life and studio practice.

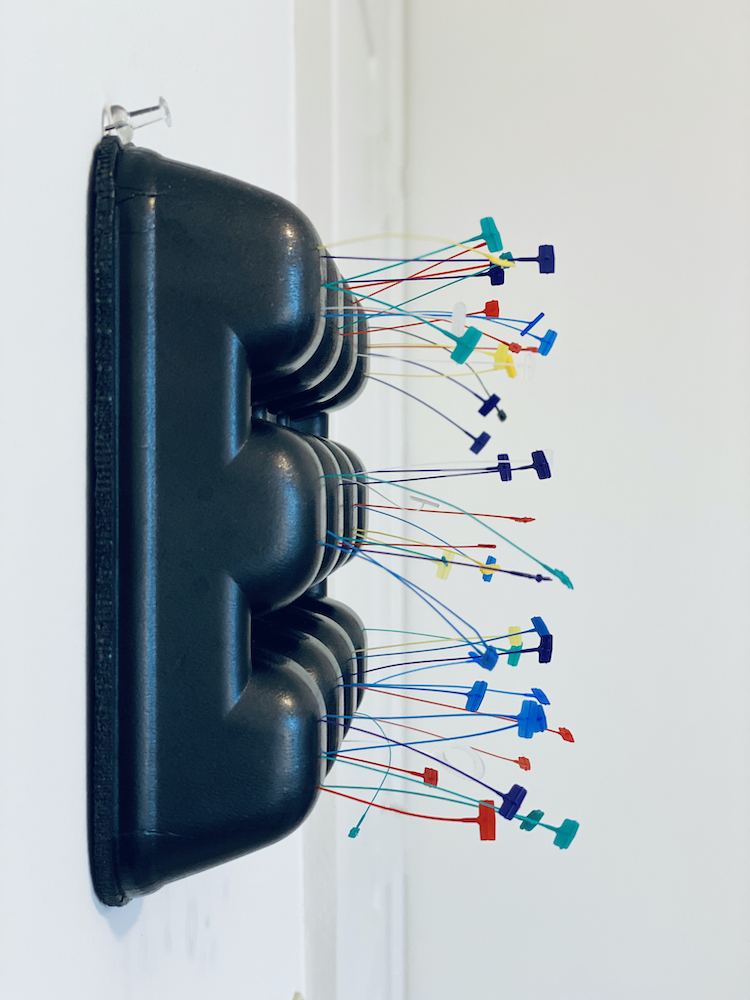

It’s not just that Oh is personable, or even that he is a good engager who lobs thoughtful questions back at the interviewer—it’s also that storytelling itself is both a part of his work and who he is as a person. As his practice is focused on mixing materials, it would be easy for viewers to see an installation of Oh’s and assume the narrative begins and ends with a meditation on the life of the found and collected materials such as plastic, wood, metals, and post-consumer packaging bits that make up many of his three-dimensional works. But I found there is more than the single story of the material; there is usually a personal tie-in, a cultural or historical reference the viewer can also pick up on if they engage with it.

Given the layered meanings his work evokes, Oh—who is also a writer and teaches writing at the college level—has incorporated text descriptions into the presentation of his work. Yet he does not insist that viewers digest his words in totality. One piece he made, while pursuing his MFA at the School of Visual Arts in New York, incorporated cassette tapes. A viewer told Oh the piece reminded him of being a child in his mother’s car and the feelings associated with that flood of memories he had not considered for some time. For Oh, this one person’s experience of the work made it hugely successful. “It managed to move this one person completely on his own terms and through his own experiences,” Oh says. “From that moment on, I decided that everyone’s going to have their own interpretations and encounters with my work, and I’m totally cool with that.”

Perhaps Oh’s personality makes him so open to the viewpoints of others, but he has undoubtedly also been influenced by his global lifestyle, living everywhere from Brunei to San Francisco, and two decades of working in the corporate world. Originally from Singapore, Oh has moved across the world more times than he has fingers and had several other careers before he moved to Baltimore with his partner in 2015.

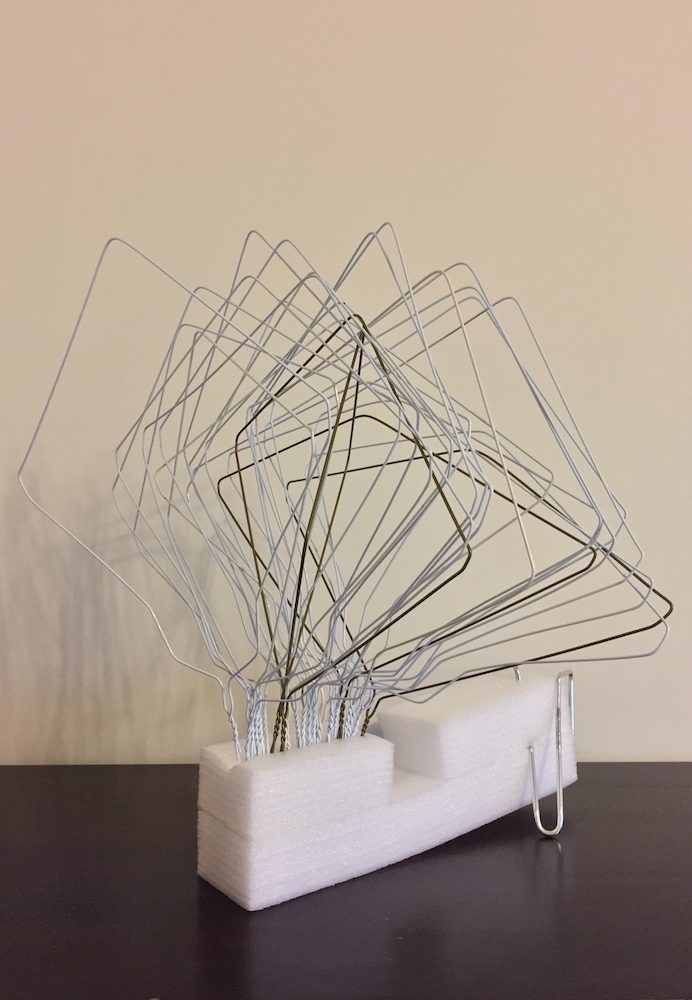

On a sabbatical from work to attend MICA’s Post-Bac program, and then as a grad student at SVA, Oh began developing work that addressed the 2001 death of his father who was a karung guni man, or junk collector. Oh intended to make paintings at SVA but felt stuck in that modality. So he turned to gathering materials from the streets and reimagining them as ready-made sculptures and installations—a practice that his dad would have found very strange, he tells me. But it’s a way of working he has since folded into his studio practice that helps him feel connected with his natural inclination towards collecting. Sitting in his studio, I took in the stacked shelves laden with boxes with labels such as “small things with text,” “dice,” and “laundry tags.” He explains that sometimes, he’s in the studio “just mucking around” when the idea to use a thing he has been saving for years strikes him. The delicious assembling of on-hand materials for such a moment has become an important element of his practice.

Oh has founded and been a part of a couple of artist collectives and recently joined Atlantika, which has nine active members located all over the world with a concentration in the DMV. Collaborating with others to exhibit work and discuss art has been essential to Oh post-school. “We’re such solitary animals; isn’t it crazy that as artists we constantly open up ourselves to the world, with all our vulnerabilities, all our animal thoughts? I just find that absolutely crazy. But I don’t think any one of us would do anything less than that,” Oh says. “As artists, we are so privileged. I always feel it’s such a privilege to feel this way, that there is this creative impulse that leaves you no choice.”

In Oh’s Mount Vernon studio overlooking Baltimore’s Symphony Hall, we talked about the fickle nature of creativity, the challenge and excitement of working with college students, and how we try every day to be the people our dogs think we are.