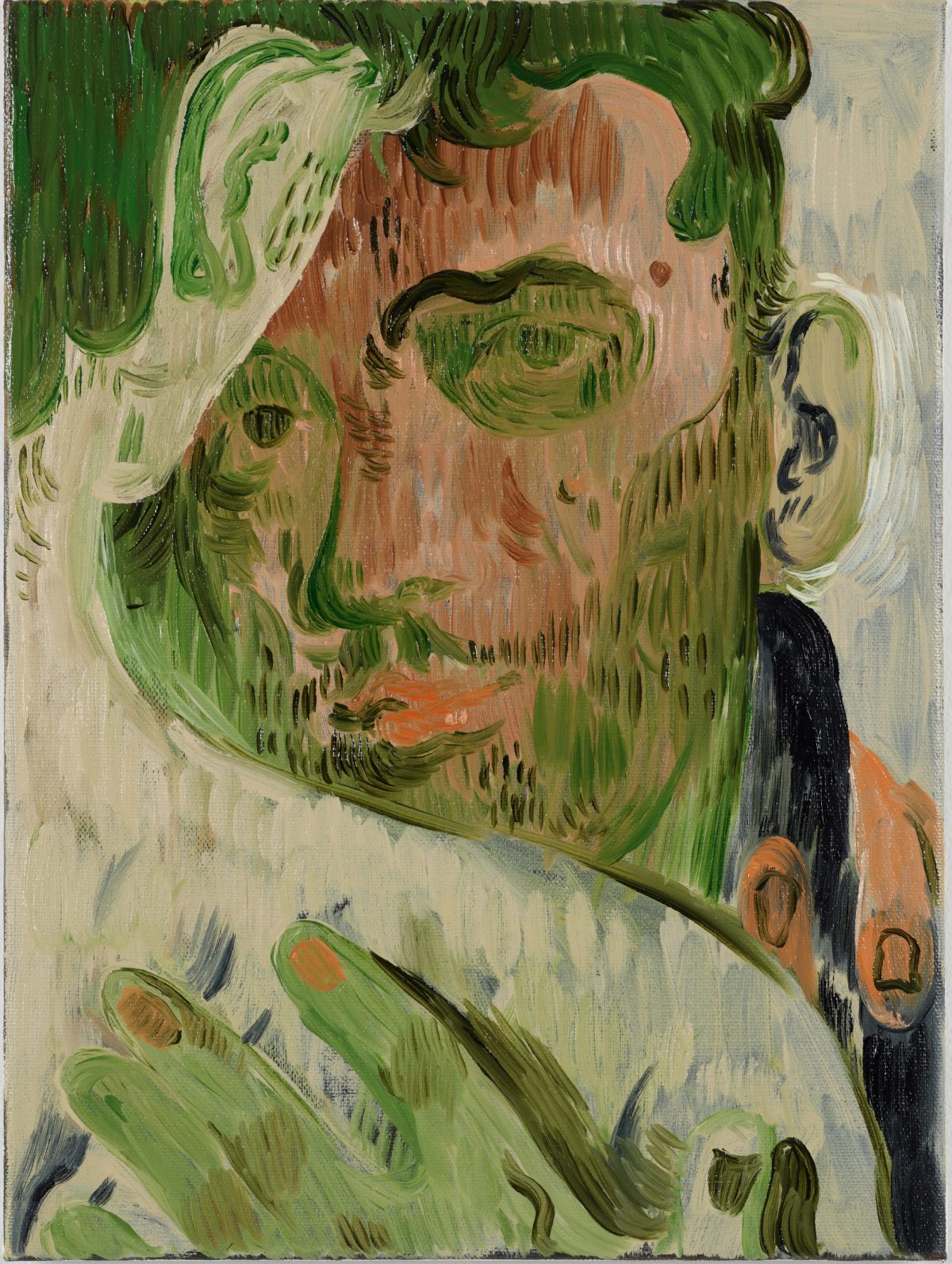

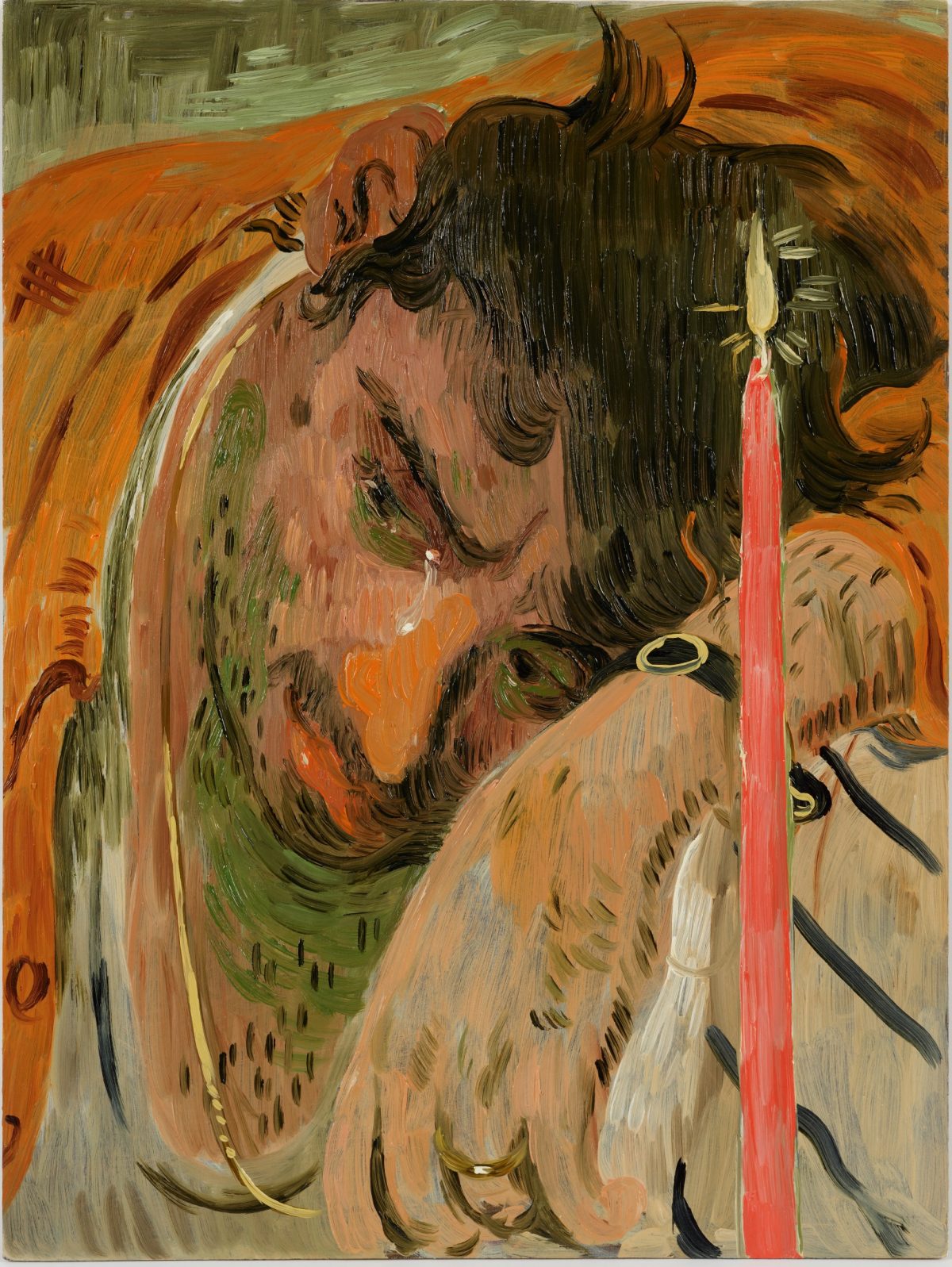

Within the deluge of gay male artists creating figurative work these days, Salman Toor stands apart from the crowd. Toor is complicated—and that’s a good thing. He’s a queer person of color, born in Lahore, Pakistan, and now living in America; his paintings are autobiographical yet steeped in references to classical paintings, and executed with the casual air of an illustrator in his sketchbook. Toor doesn’t use models or photographs as references for his paintings, relying instead on small sketches, memory, and imagination.

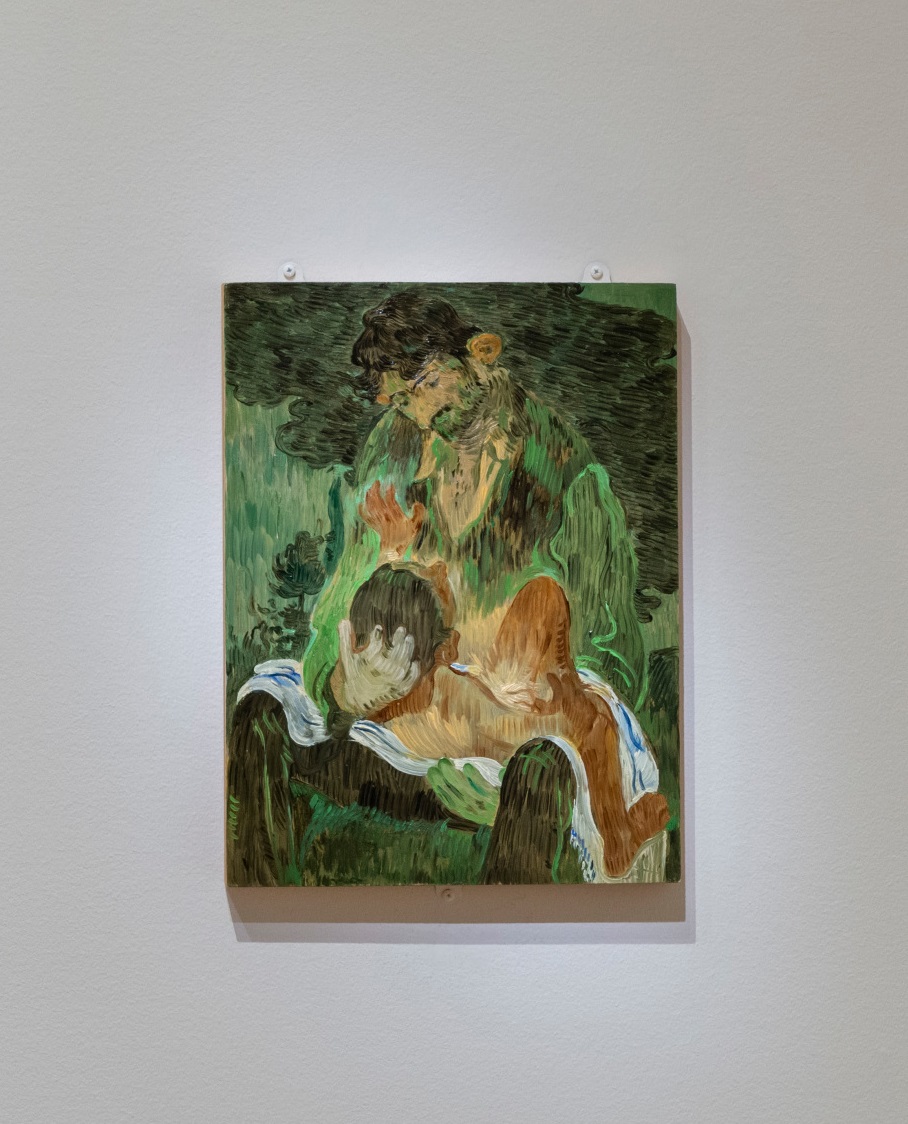

In No Ordinary Love, the artist’s second institutional solo exhibition, now on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Toor’s separateness and distinction are depicted quite literally in his painting The Latecomer. A lone young man walks toward the middle of a bar while the other patrons stand clustered and preoccupied. The protagonist, dressed in white, is cast in stark relief against the rich and glossy emerald, celadon, and sea greens of the room, as if he appeared in this homogeneously-hued world by some twist of fate. Is standing in contrast with the world around him delightful or dangerous? At the moment, just one figure in the bar seems to notice the latecomer, a man in the foreground offering a mystery cocktail along with his stare.