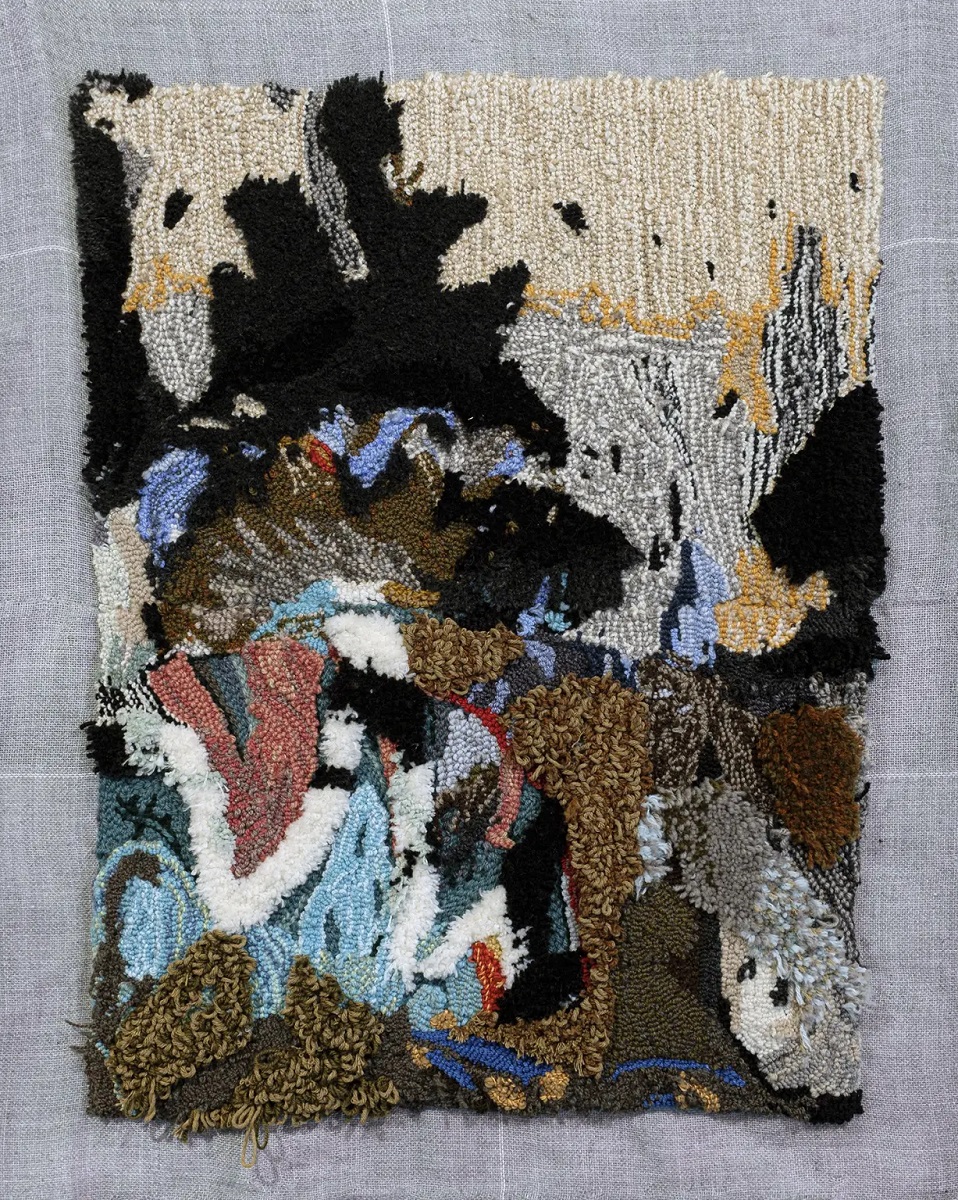

The first time I saw reproductions of the Maryland-based artist Randi Reiss-McCormack’s fiber-based paintings, I thought, “This person’s work deserves a museum show.” Museums came to mind more vividly and emphatically after seeing, in person, her canvases’ extreme, unique physicality. Right now I’m thinking, “Good for the Myrtle Beach Art Museum,” in South Carolina, where her work is presently on display (January 10-April 16th).

You could kick up your heels, rollicking through the hectic, compressed spread of the mammoth, four-part, visually seamless “Prowling the Undergrowth.” On the flip side, you could lose your way, your breath, the beat, trip over a serpentining vine, or step into a rabbit hole in the undergrowth’s ungreen greenery. But it wouldn’t take long getting back in sync or picking back up the beat, because standing before “Prowling,” we’re not just ordinary viewers of paintings or weavings; we embody the poetics of sharp-eyed ears and hearing eyes.

This extraordinary jumble of a textiled jungle makes for a robust trek. How we trek from here to there—with all the missteps we might delight in on our mazy, crazy path—matters.