How do two artists who study the urban landscape approach ecology? Lynn Cazabon and Andrea Sherrill Evans’ work doesn’t have much in common formally. Cazabon, the Director of the Center for Innovation, Research, and Creativity in the Arts at UMBC, works primarily in photography and new media. Evans, faculty in MICA’s Drawing department, is a draftsperson working in traditional materials.

Conceptually, both artists explore nature through their practices and advocate for its protection. For these two transplants working in education—Evans hails from Tempe, Arizona, and Cazabon from Detroit—Baltimore’s landscape has become important to their work.

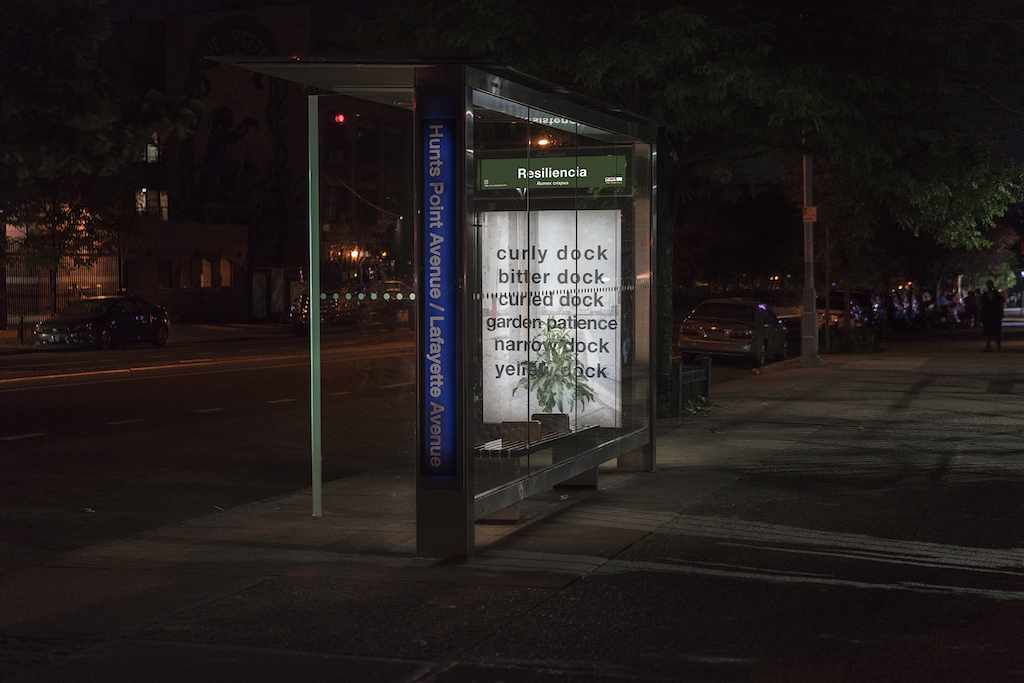

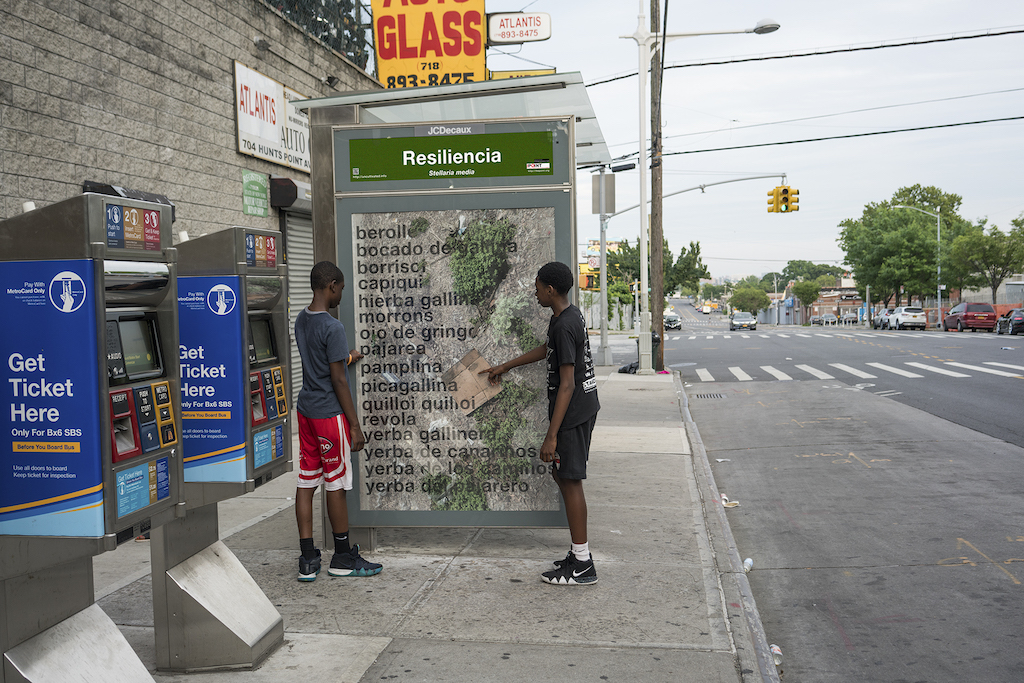

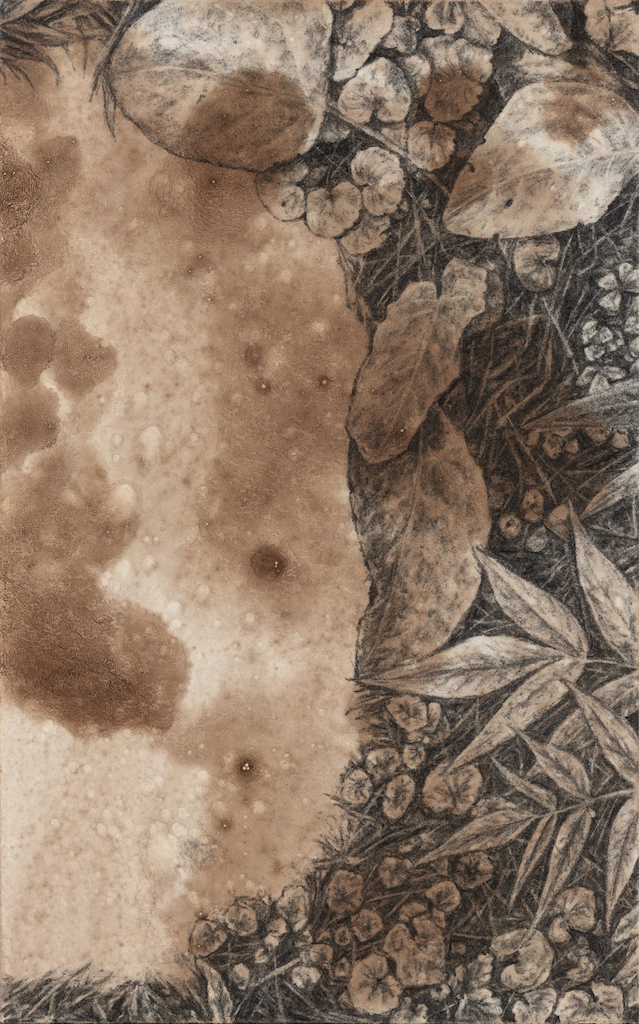

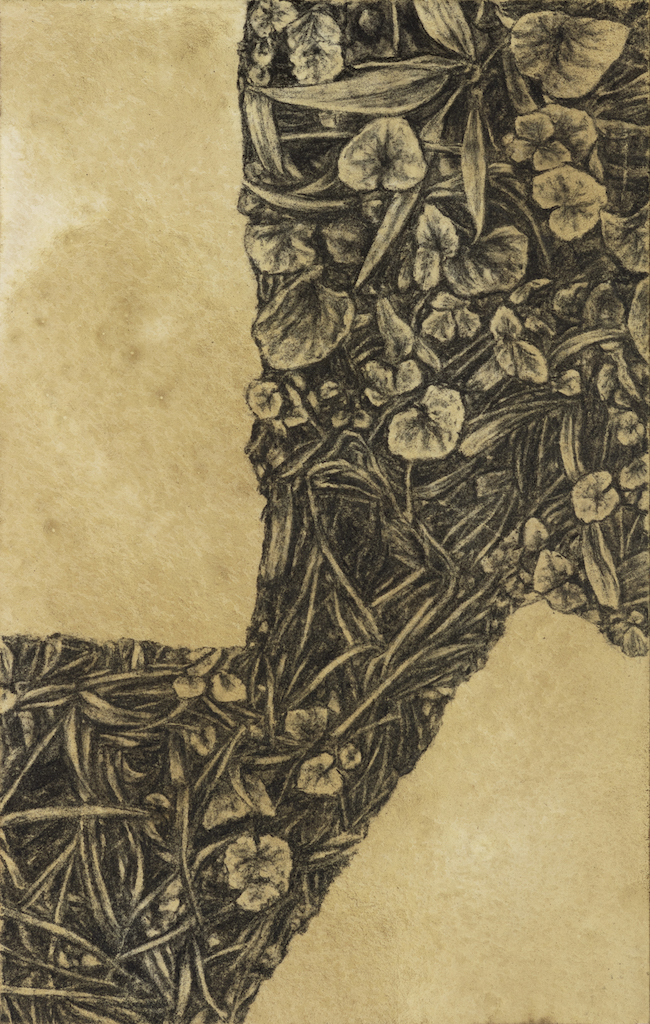

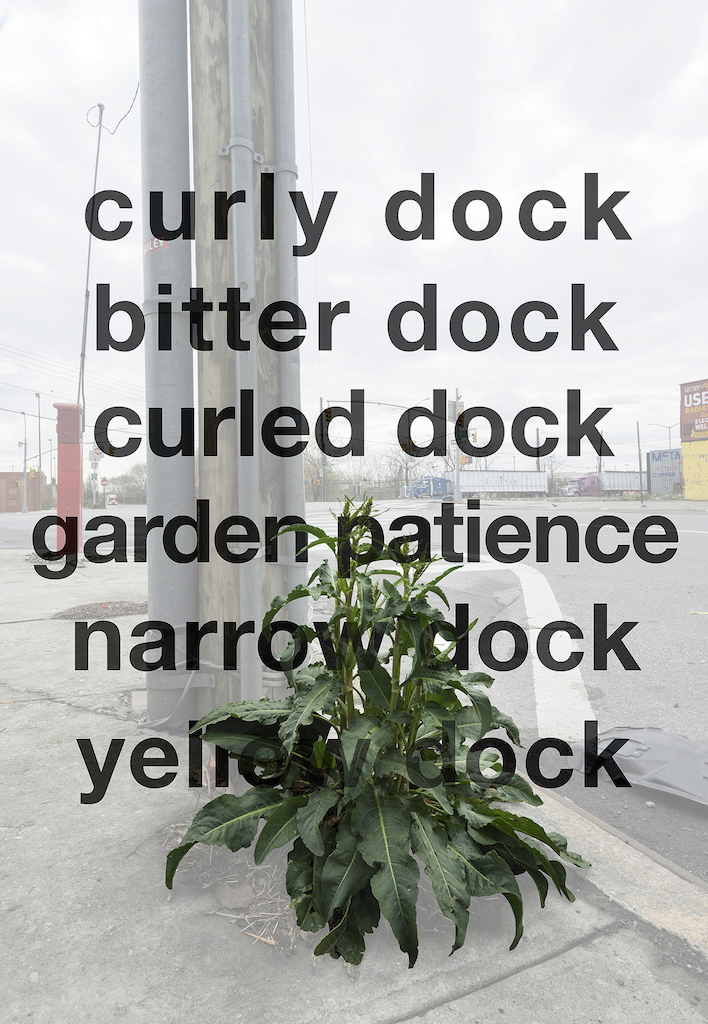

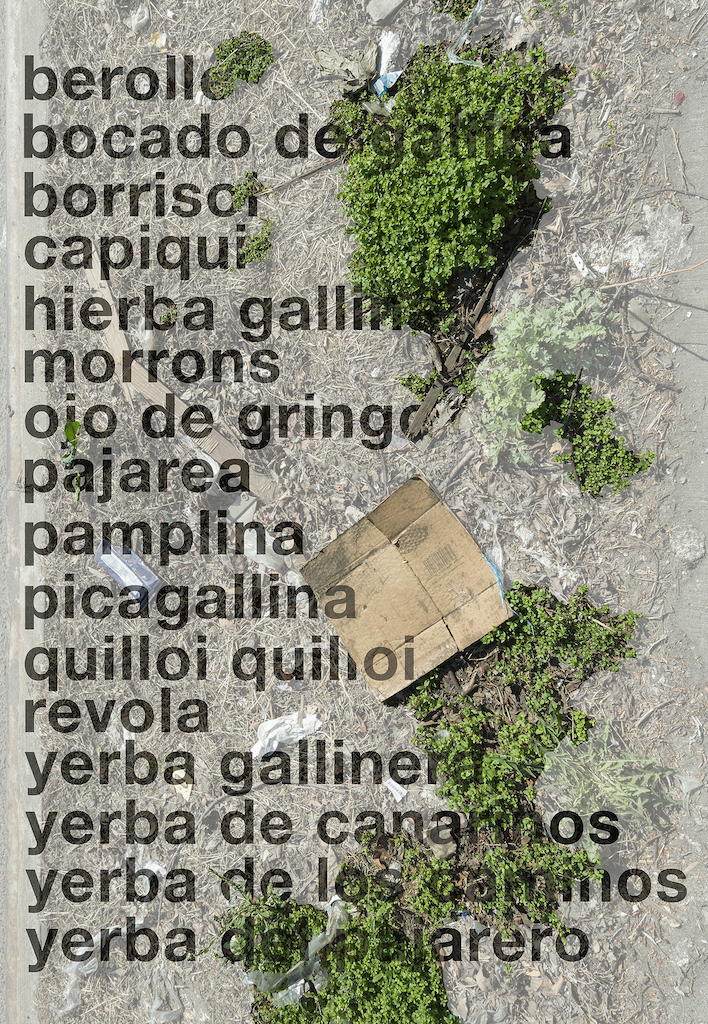

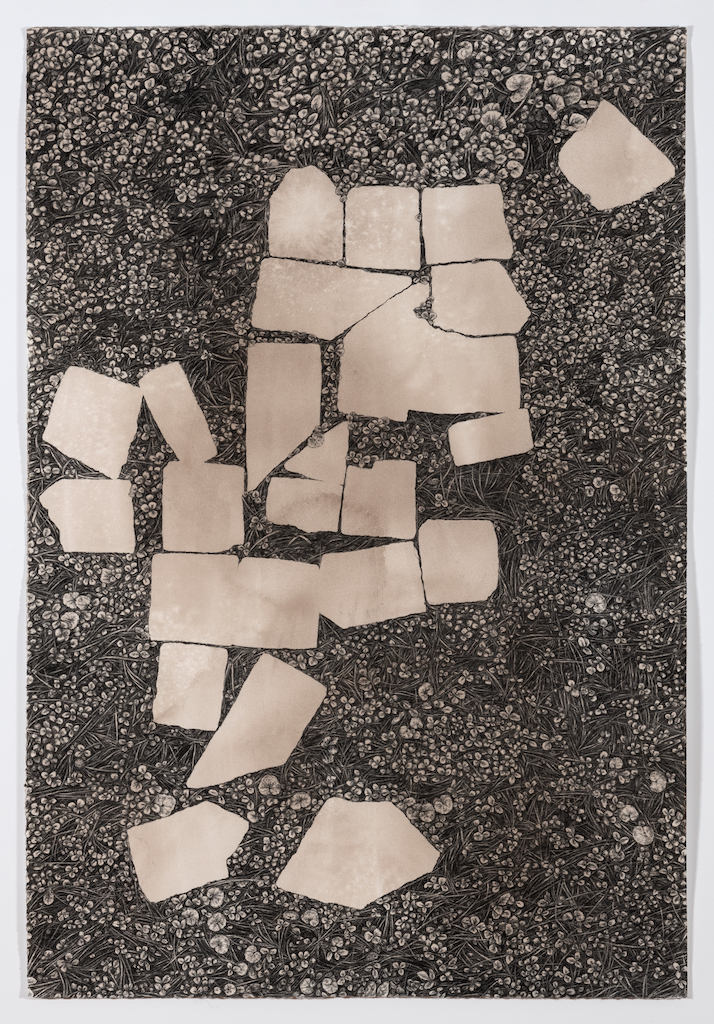

Since 2019, Evans has explored connections between her materials and subject matter, making inks and charcoals from foraged botanical sources. This process allows her to ponder the close relationship between observational drawing and the experience of gathering plants. Cazabon’s photographic practice involves site-specific installations, augmented reality, and public dialogues about the effects of climate change. Her focus is on the social exchange between viewers of her work.

In their first conversation, recounted in an edited form here, the artists quickly found common ground discussing their processes, gardening habits, and close observations of the effects of climate change on the natural world.