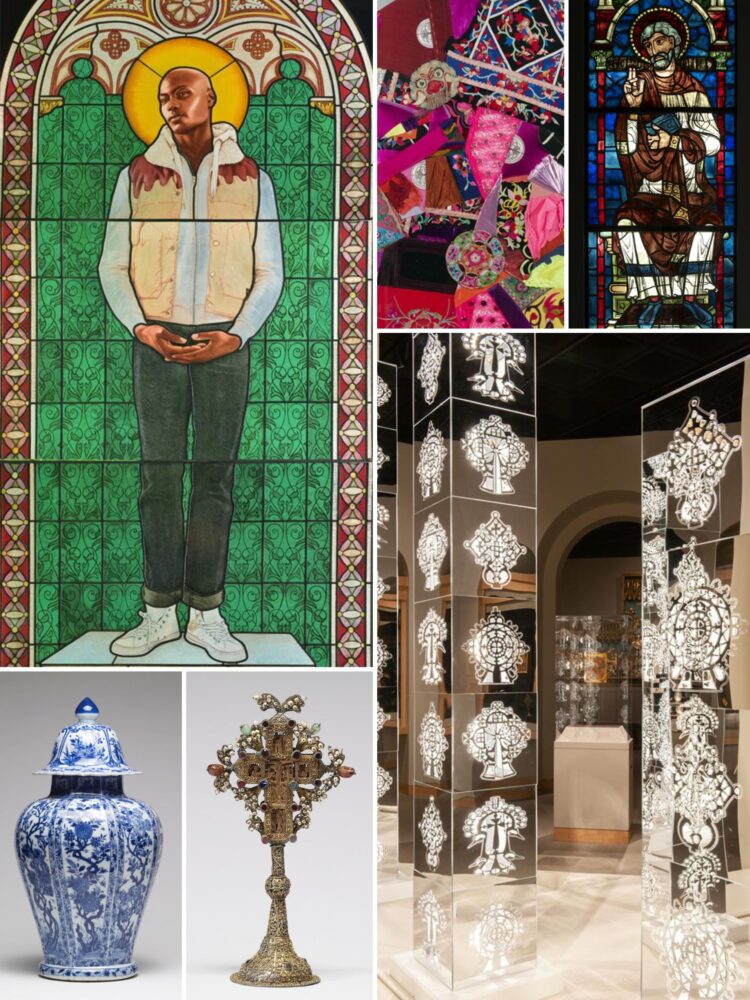

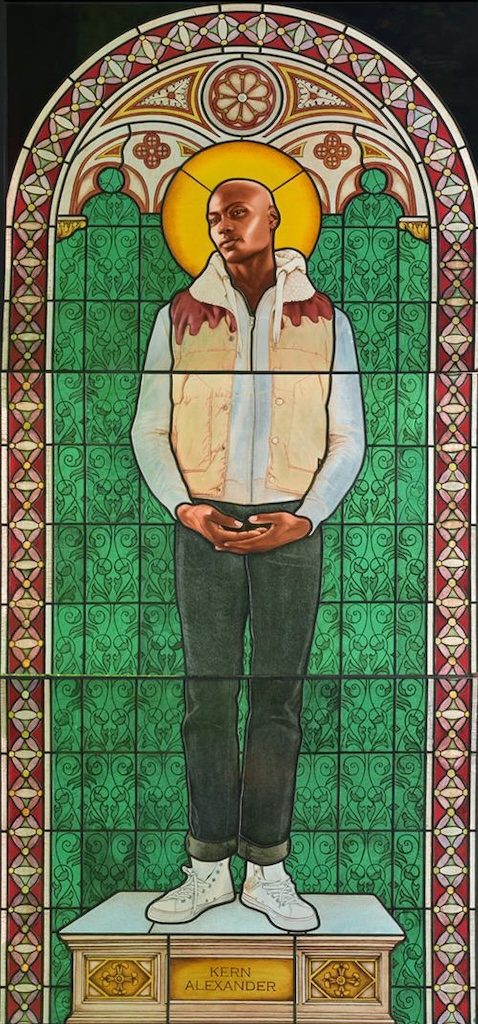

Close by Makonnen’s work is that of art star Kehinde Wiley, best known for his majestic, foliage-set official painting of President Barack Obama for the National Portrait Gallery. Now on view following its recent acquisition by the Walters, Wiley’s angelic, stained-glass portrait, Saint Amelie, from 2014, hangs among numerous ancient artifacts in the museum’s hallowed space.

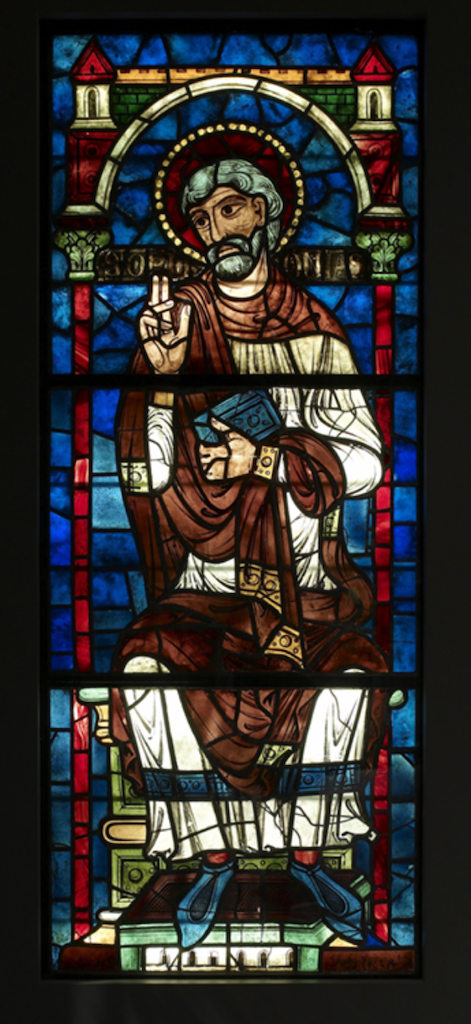

In contrast to—yet also in harmony with—Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s 19th-century stained-glass work of the same title, Wiley’s glasswork portrays a young, serene Black man of today, rather than the eighth-century Christian saint. Instead of robes and sandals, his saint, Kern Alexander, wears Converse sneakers, cuffed jeans and a hoodie—typical garb of any ordinary city man the world over. Wiley’s work asks for a moment of pause to absorb and pay respect to such men who have maintained strength in the face of unremitting discrimination, inhumanity and—in many cases—violent premature death. Keyed to a color palette of rustic reds, Victorian greens and mired gold often found in African nation flags, Wiley also alludes to the rich cultural heritage of those regions, the roots of his subjects.

The artist has said his works are commentaries that critique and celebrate history but can also be “mysterious and snarky” with the potential to “change the world.” By looking back to the past and rewriting time-honored, culturally inculcated artistic formats with subjects of the present, Wiley gets to compare the original value of those early works, their reinforced importance—right or wrong—over time, and the paradigm shift that gives them their value today.

I asked a few art museum professionals about their experience in the decision-making process to acquire and display newer works with largely historical collections. Some spoke of urgent institutional protocols, while all agreed about the need to address the cohesion and discord of art across cultures, as well as redress wrongs of the underrepresented.

A spokesperson for the Walters Art Museum explained that the museum “prioritizes acquisitions that bring new representation and new voices into the collection and that provide opportunities to create new juxtapositions and narratives.”

While some art institutions have been following the American Alliance of Museums’ landmark Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion strategic plan set forth 2017, many found time to more profoundly change their programming when the 2020 pandemic shuttered museum doors across the country. The Walters collecting directive and subsequent donor gifts began to include more contemporary works, as well as lesser-seen historic works of significance, such as an 18th-century painting by the biracial Baltimore-based portraitist Joshua Johnson.

From the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, Chief Curator Elsa Smithgall spoke about that museum’s longstanding policy to show older works along with contemporary ones.

“There have been many changes in museum operations and policy since 2020, and a lot of reckoning around social justice and—now especially—warfare issues. Founder Duncan Phillips wasn’t shy about his focus to show the richness and diversity of American art alongside work from French, German, or Japanese artists. The world has become even more global because of the Internet and virtual communications, so that distances and differences no longer feel so great,” Smithgall explained.

She recalls reactions to a “high-contrast” installation: “We showed a folk art painting by Horace Pippin with a new hi-tech light work installation by Leo Villareal, and many viewers resonate with these diverse work mixtures, while others are sometimes baffled.” So, exhibition staff often create context for viewers with descriptive object placards, audio guides or special cell phone apps.

Many museums, such as the Phillips, increasingly receive grants from sources like the Terra Foundation for American Arts to create “a more inclusive model to bring forward underrepresented aspects of our history,” Smithgall said.

RISD Museum of Art Curator Emerita Jan Howard points out that the current move to mix and match old, new and different artworks has a longer history than we might imagine. The early 1990s saw a revitalized focus on critical theory that supported interest in multiculturalism. “The first time I can remember being involved in a project that juxtaposed contemporary and historical works was at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where I worked with curator George Ciscle and his MICA graduate students on the 1999 exhibition Joyce Scott: Kickin’ It with the Old Masters,” Howard said. “It was such a privilege to walk the galleries with Joyce and see the collection through her eyes, for she had selected works across time and cultures to place in dialogue with her own art.”