Baltimore City Paper: Rental Wonderland: The City Art Building’s gallery steps up its game By Baynard Woods

Smorgasbord Through Feb. 1 at Gallery CA; opening reception Jan. 18

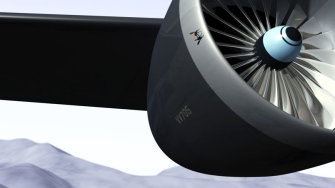

In Don DeLillo’s novel Underworld, the artist Klara Sax is painting decommissioned Cold War jets in the middle of the desert. Much of DeLillo’s work is defined by the recognition—which we can see in Sax’s character—of the strange, cold beauty of our technological instruments of war. A similar sentiment seems to motivate local artist Matthew Fishel, whose super-sleek HD animation loops show the surface beauty of airplanes. This is evident in 2011’s “Mother Duck,” a beautiful five-minute animation of a bomber jet. The jet, followed by 11 silhouetted bombs, occasionally flaps its wings like a bird, the bombs drift ever so slightly downward before propellers on their tails spin and they raise back up, as if caught in their “mother’s” draft. Read it here.

/////////////////////////////

London Evening Standard: Damien Hirst’s pickled cows help Tate Modern pull in record 5.3m visitors

The blockbuster Damien Hirst exhibition helped drive Tate Modern to record visitor numbers last year, it was announced today.The giant retrospective of many of the British artist’s most famous works attracted 463,000 people out of a total 5.3 million.

The opening of the Tanks — the first part of the Bankside gallery’s new extension — in time for the London Olympics, and the quirky Turbine Hall commission of moving and chanting volunteers orchestrated by the artist Tino Sehgal as part of the Cultural Olympiad, also contributed to the record high.

Alex Beard, Tate’s deputy director, said: “It has been an extraordinary year at Tate Modern, opening the Tanks, the world’s first museum galleries permanently dedicated to exhibiting live art, performance, installation and film works, alongside an outstanding exhibition programme which has undoubtedly fuelled the increase in visitors.” Whole article here.

////////////////////////////////

Brown Paper Bag Blog: Tom and James Draw

I first feasted my eyes on this painting via Pinterest a couple of days ago:

Not attributed to anyone, I did a little digging and found out that this piece is actually a collaboration between Tom and James Hancock, two brothers that hail from Australia. Their collaboration is a unique one, as Tom is an adult living with Down Syndrome. His brother James, who has made a career with his illustration and art, created Tom and James Draw, a website that shares their works. He writes,

Their collaboration is unique as they are sharing experiences between the outsider and “insider” art world. James identifies with Toms abstract use of visual coding and Tom builds around James’ skilled and confident mark making. Tom relaxes James’ technical obsessions, and James enables Tom’s concentration and playful markmaking. Together they make worlds of experience, encompassing people around them and their actions, animals, plants, engines, and sometimes hilarious nods to the human experience and perception.

Lovely. All images via Tom and James Draw. http://www.brwnpaperbag.com/2013/01/09/tom-and-james-draw/

/////////////////////////////////////

Saltz: MoMA’s Inventing Abstraction Is Illuminating—Although It Shines That Light Mighty Selectively

By Jerry Saltz

Early-twentieth-century abstraction is art’s version of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. It’s the idea that changed everything everywhere: quickly, decisively, for good. In “Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925,” the Museum of Modern Art’s madly self-aggrandizing survey of abstract art made in Europe, America, and Russia, we see the massive energy release going on in that moment. Organized by Leah Dickerman, the show is jam-packed with over 350 works by 84 painters and sculptors, poets, composers, choreographers, and filmmakers. The sight of so much radical work is riveting.

Yet art of this kind still poses problems for general audiences. They look on it warily. Indeed, even we insiders sometimes don’t get why certain abstraction isn’t just fancy wallpaper or pretty arrangements of shape, line, and color. It can take a lifetime to understand not only why Kazimir Malevich’s white square on a white ground—still fissuring, still emitting aesthetic ideas today—is great art but why it’s a painting at all. That’s the philosophical sundering going on in some of this work, the thrill built into abstraction. Insiders will go gaga here. But I wonder whether larger audiences will grasp the way this kind of art thrust itself to the fore in the West, coaxing artists to give up the incredible realism developed over centuries by the likes of Raphael, Caravaggio, Ingres, and David. Whole article here.