A review of Ken Price’s unique contribution to fine art by Jascha Owens

In his seventeen page hand scribed manifesto “Memo to M.F.A. Students Who Use Clay,” which would be more aptly titled “Memo to M.F.A Students, Artists and Critics,” Ken Price calls attention to the shifting relationship between fine art, craft, criticism and public reception over the last century. This is a must read for all artists and thinkers concerned with cultural evaluations of art. For those who appreciate Price’s luminously glazed ceramic blobs and slump forms, especially the roughly sixty-five currently on display in Ken Price Sculpture: A Retrospective, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you will find great solace in the sincere affirmations of the ideas pursued over his lifetime.

Many topics are covered in Price’s Memo, none the least of which is the importance of craft in art, which, for better or for worse, always seems to come up in critical discussion of Price. Perhaps rightly so, as John Yau points out in his Hyperallergic review, “I found it perfectly in keeping with long held policies and biases that the show — curated by Stephanie Barron, who is chief curator of modern and contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, with assistance from Lauren Bergman — went to the Met from LACMA and not to the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum, or the Whitney Museum of American Art — three institutions which have all but openly declared their hostility toward the craft tradition to which Ken Price, who worked in ceramics, clearly belongs.” Although Yau is right to point out this bias, part of me can’t help but feel this discussion only perpetuates the craft stereotype Price so adamantly fought against in his career and manifesto. Experiencing the retrospective in the moment, I saw so much authenticity, dedication, personality, and conviction that I couldn’t be troubled with whether what I was looking at was a sculpture, a painting, or craft.

As I write this, aware of the hypocrisy in continuing Price’s craft associations, I’m compelled to stop and instead focus on the brute emotion that overwhelmed me in the presence of his work. I don’t want to devalue the component of craft in Price’s work, for he was a champion of pottery and their craftsmen. His work obviously contains the qualities of skillful handmade objects and he was extremely educated about the history of craftwork in society. Perhaps Price relished the challenge of presenting craft to the Clement Greenbergs of New York? However, I believe he hoped for a world where the distinction between fine art and craft became irrelevant, a place where it is accepted that craft is a basic component of art, and where decoration is inherent in craft. At the very least, I can attest to fantasies of such a place.

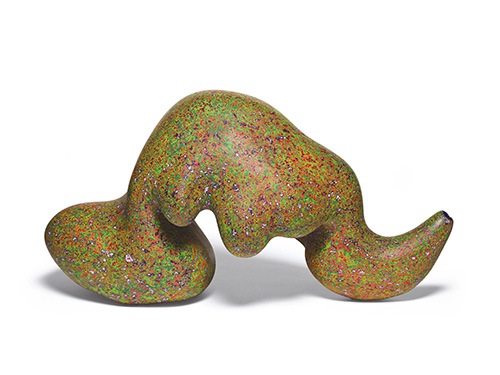

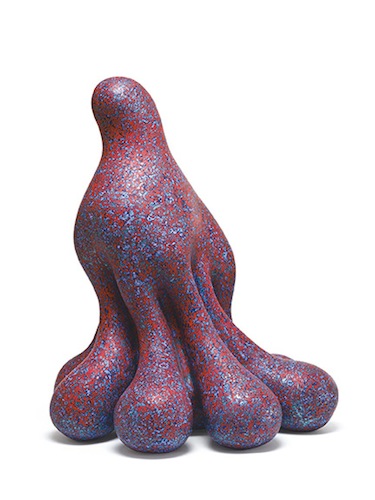

What is it that made me so obsessed with the work of Ken Price? This was a question I kept asking myself in the months leading up to his retrospective at the Met. Admittedly, my forays in sculpture and pottery are limited to all but a few elementary school projects, which probably lie in some dusty corner of my mother’s garage. Even as I began dedicating myself to the scholarly study of art I tended towards the two dimensional. There is of course the obvious answer that Ken Price is more painterly than most sculptors. But there is certainly something more, something unassuming, funky and psychedelic no less, about Price’s modestly sized organic forms.

Oddly enough, I think it was Lawrence Weschler’s biography of Robert Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, that initiated my attraction to Price’s work. I don’t think there is much mention, if any, of Price in Weschler’s book but he does a wonderful job of painting the 60’s and 70’s California scene. Irwin, De Waine Valentine, Helen Pashgian, John McCracken, Mary Corse and Larry Bell, who’ve been pigeonholed as “Light and Space” artists, were and still are dealing with the phoneme, experience and sensation of light/ atmosphere/ architecture/ what have you. A well respected contemporary of theirs and fellow Ferus Gallery member, Price, meanwhile, was busy making mugs and ‘Jazzing Glass’ (surfing, not glass blowing). Yet he shared the “Light and Space” artist’s desire to work primarily with materials instead of concepts. Aptly removed from the high intellectualism of New York City, artists like Pashigian describe a freedom from art jargon or having to justify oneself in the budding community of Los Angeles. Everyone was in a sense, simply playing with new toys (resins, plastics, etc…) and letting the results speak for themselves.

As much as I’d like to believe it was all true, that these California artists were just messing around in cheap garages before bonfires on the beach, it’s hard for me to shake the seriousness from works like Irwin’s Line Paintings, of which he produced only ten in two years of practically non-stop studio work. The way Bell’s constructions still the atmosphere, or the austerity of Valentine’s columns, all gush of minimalist language and practically beg to be in conversation with the likes of Donald Judd. Works like Price’s L. Blue, sexually charged, bulging and awkward, show no regard for New York let alone any singular high art movement. He, of all the California artists, seemed to command personal conviction unscathed. Never was Price enticed by the powers of the fine art market during his career, as exemplified by his posthumous retrospective at the Met, the first and only of its kind. Unlike Irwin and the rest of his colleagues at Ferus Gallery, Price made objects unconcerned with the trends of Minimalism and Pop Art in New York. He stuck to what truly interested him: Mexican pottery, craftsman culture, and handmade objects. Though he was obviously aware of the history of fine art and the importance of critical dialogue, he maintained true to his own concepts of art.

I had planned to describe the intensity with which I relished my experience seeing Price’s work for the first time in person last month. To recount the height of my expectations and how Price surpassed them nonetheless. But I suppose I let my inner art critic get the best of me. Maybe it was for the best, for I can think of no better justice to Price than to simply say you must see the work for yourself. You need to stand there and submit to it, feel the urge to fondle it’s oozing extremities, and leave with a confusing asexual arousal after having witnessed some of the most authentic things to grace fine art.

*Author Jascha Owens is a Baltimore-based painter and a recent MFA graduate of MICA’s LeRoy E. Hoffberger School of Painting.