“People often collect the art of their time, so why not collect the art of your own place? Especially if you live in a cool place like Baltimore.” says Doreen Bolger, Director of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Bolger, a former curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and director of the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum, is an avid collector of artwork created in Baltimore. At this point she has lost count, but it’s not unreasonable to estimate she owns close to a hundred works by local artists. Tucked into a Charles Village brownstone with William Morris wallpaper, Bolger’s art collection is not what you would expect of the director of a major museum with a background in 19th century American painting. There are no Eakins’s or Sargents or Coles. There are no contemporary works bought at NY auctions, or any worth millions of dollars. Rather, Bolger’s collection features work by a growing group of emerging artists that are her friends and colleagues in Baltimore.

Her house is filled with local art. There are large, freestanding sculptures, paintings, and prints in her living room. There are tiny sculptures on her mantle. There’s a giant wall sculpture by Hermonie Only in the dining room and Dina Kelberman drawings in the kitchen. There’s an Andrew Liang soft sculpture animating a back staircase and Matt Bovie and John Bohl paintings in the bathroom. Everywhere you look, even in hallways and winding staircases, there’s contemporary art made in Baltimore.

“People don’t understand this, but if you look at the collections of Henry Walters or the Cone Sisters, many of the things now in museums were originally collected as contemporary art,” Bolger explains. Rather than an economic investment or an excuse to brag, Bolger sees the work in her collection as companions, representing memories and relationships. Some of the works, including the Gaia raven print in her living room, are collected as part of fundraisers and local auctions, while others were purchased from exhibitions at DIY galleries and non-profit art spaces in Baltimore.

As with many art collectors, she didn’t start intentionally. Rather, it evolved organically, a byproduct from her work in museums. “In the beginning it wasn’t a collection. It was just stuff I happened upon, stuff I had,” admits Bolger.

She bought one of her first pieces when she was director of the RISD Museum in Providence, RI. David McCaulay, illustrator and author of ‘The Way Things Work,’ was faculty at RISD and Bolger was drawn to the charcoal drawing because it was based on a Chinese sculpture in the museum and depicted a house similar to hers. Several years earlier, she was given four small, ceramic figures from ‘Field of Figures,’ an Anthony Gormley installation of 100,000 that filled Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth, TX. “My children, who were about three and four at the time, loved it so much,” she says. “We would go every weekend to see this installation and sit up high and gaze down on it for hours,” she remembers. The figures now adorn a living room windowsill, a physical reminder of this time in her life.

When Bolger came to Baltimore in 1998 to direct the BMA, she brought those pieces, along with a few works by J. Alden Weir, on whom she had written a book. The works by Weir are now promised gifts, part of the BMA’s collection. Although she is attached to the pieces she purchases, she invites BMA curators over periodically to look over her collection and offers them “anything they want,” as they make their acquisition recommendations to the Trustees.

A few years after arriving in Baltimore, Bolger began attending local art exhibits regularly. Today, she is everywhere, a ubiquitous figure at most art receptions – from gritty warehouse spaces to pristine galleries, throughout the city. Although they don’t always show it, local artists are thrilled to see her at their exhibits; her presence energizes the room. “Showing up really matters,” Bolger says. “It’s a really important thing, whether you’re a politician or a leader of an arts organization, college or university.” She says that buying art became a natural extension of attending art openings regularly, and encourages others who may not know where to begin to simply start by showing up.

“If people are showing up, then they’re looking around. Then they realize they can take a piece home. Then one thing leads to another. If you show up and start talking to artists, you can’t help but become interested in what they’re doing. The next step is when you are so interested in a piece, you want to see it every day.”

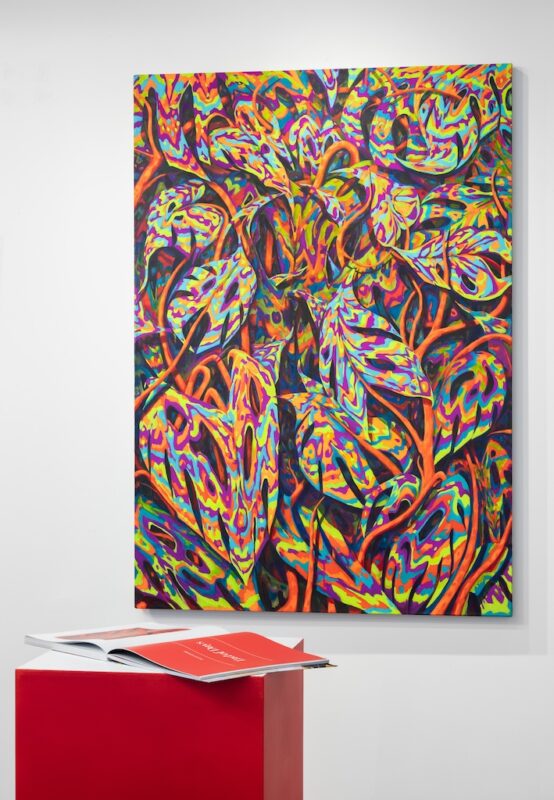

Bolger admits that she has a taste for artwork with patterns, that this may be the unifying visual quality in all the works she owns, but says that, for her, it’s also about curiosity and beauty. “Sometimes I’ll see a piece of art and think it’s really beautiful, and I’ll wonder what it’s about, especially the more abstract the piece is.” Although some artists are reluctant to explain their work, Bolger suggests that a conversation with a viewer is the best way to create more options for becoming attached to a piece of art.

“Beautiful objects are just as appealing to me as something with a meaning or association that resonates. For example, the Gaia ‘Raven’ image is beautiful, but it’s about Edgar Allan Poe. And Poe is tied to Baltimore, which makes it more appealing.” Bolger further clarifies by suggesting that artists should always make the titles of works available, that many artists don’t, and that this omission makes the process harder for a viewer to relate or feel a connection.

According to Bolger, communication is essential for making Baltimore art more available to collectors. She also urges artists to work harder to make potential collectors and art world outsiders feel welcome in a gallery setting. “If they’ve shown up for the first time at an event, make them feel welcome. Then there’s the communication about the work – why did you make it? How did you make it?”

Bolger admits that buying art can be intimidating and the art world can be too cloistered. “It’s a complicated thing,” she says, in response to a question about Baltimore’s lack of serious, local collectors. “For example, people ask me about the Station North Arts & Entertainment District and I tell them it’s kind of ‘underground’… You can find it on the Internet, but there aren’t many published addresses, and you have to really pay attention to know where these places are. If you’ve never been there and you are my age, like many collectors are, it’s a little bit frightening to climb up three flights of stairs in the Copycat building.” Then she counters with a smile, “But it’s totally worth it.”

Bolger continues, “I think people just don’t know where venues things are and they don’t feel comfortable unless they know someone will be happy they’ll be there. We brought our docents from the museum on a tour to Oliver Street last year. We went to Area 405, Gallery CA, and The Tool Library, and they were completely charmed. They had no idea. Usually we take them to New York or Philadelphia, somewhere there’s a big show, but afterwards one of them said, ‘I felt like we were in Brooklyn.’ And I said, ‘It’s better than Brooklyn.’”

Regarding potential Baltimore collectors, Bolger says that those who can afford to collect art regularly have no idea how much it means to an artist to sell a work, and how important the act of purchasing work is. “If just ten people would spend $10,000 a year -OR- if 100 people would spend $1,500 a month buying art in Baltimore, that would change everything,” Bolger explains. “The artists I know and love could quit one of their dishwashing jobs and have more time to make work.”

Bolger also cites the importance of the galleries in Baltimore for supporting artists careers and the significance of purchasing work from local galleries as a part of the local creative economy. “If you look at galleries that were important to us, but are now closed – Open Space, after the fire, and Nudashank – those are serious losses. Those were forums where people got together and exhibited, with real curatorial perspective.”

Author Cara Ober is a Baltimore-based visual artist and curator. She is the Editor in Chief at BmoreArt.