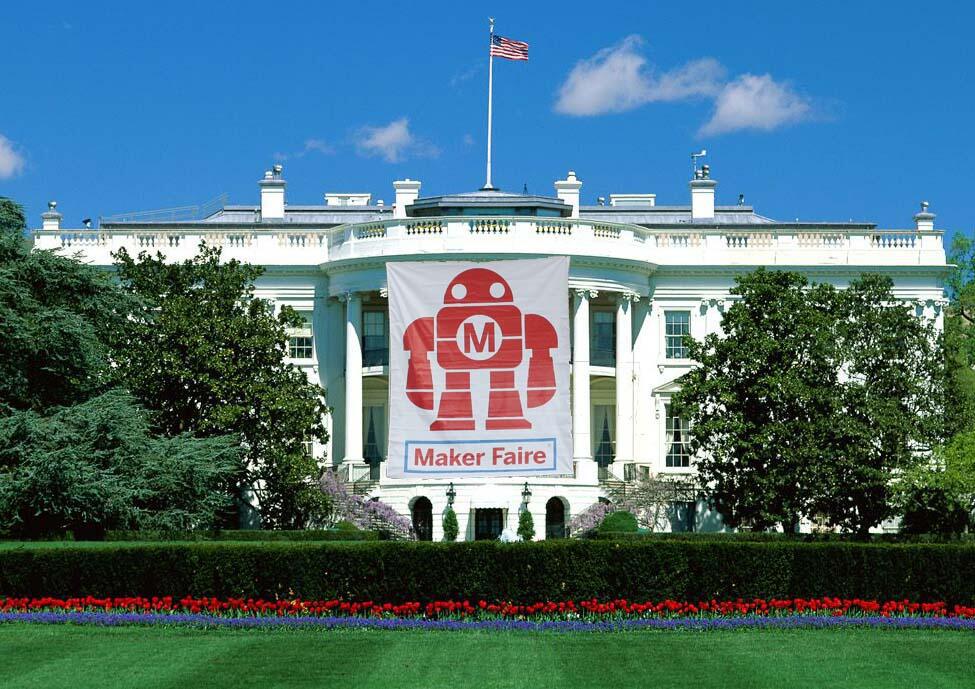

A few weeks ago, a robotic giraffe named Russell strolled up to the White House. There’s no punchline—only a handful of photos and Vines that prove Russell’s attendance at the first ever White House Maker Faire. The giraffe was one of dozens of quirky inventions and technology demos at an event that officially stamped the POTUS seal of approval on a revolution that has been years in the making.

Maker Faires like this have been held around the world, providing opportunities for artists and inventors to share their creations with the public. June 18th saw the White House play host to cupcake-bicycle-sculptures, a digitally controlled pancake conveyor belt, a banana-based musical instrument, and a functioning Mars rover built by teenage sisters. Geek celebrities like Bill Nye milled amongst politicians and the press, their enthusiasm echoing throughout the social media landscape. As this day of spectacle made clear, the Maker movement had reached the mainstream, threatening to influence the future of economics, education, and even art. So just how did the Maker movement bring something as uncool and geeky as Dungeons & Dragons into President Obama’s 2013 State of the Union address?

Years ago, amidst the coffee-fueled offices of post-Internet California, a magazine called Make was founded in 2005 by tech nerds longing for something more than the digital sheen of their computers. It had roots in the Do-It-Yourself ethos of the punk movement, the affordability of digital technology, and maybe the confluence of ambitious and clever Californians with too much time on their hands. Make-founder Dale Dougherty and editor-in-chief Mark Frauenfelder created a publication of simple electronics tutorials and cool projects like building your own quadcopter. Make defined a loose movement that also encompasses the website Instructables, television’s Mythbusters, open-source hardware like the Arduino microcontroller (a tiny computer used to control physical interfaces), and the ever-growing popularity of the handmade. Rooftop gardens, craft beer, knitting—-you know the smell of DIY.

Make magazine held the first Maker Faire in 2006, and today Maker Faires, Mini Maker Faires and other sub-types are held around the world from Greenbelt to Ghana. There are 111 Maker Faires scheduled in 2014. Will the movement continue to grow? Is it even a movement? And what does it mean for artists?

First, some clarification on confusing terms. Fablabs (short for Fabrication Labs) are specific workspaces designed according to the standards of the original MIT Fab Lab. These spaces offer equipment for digital design and fabrication to the public, though they are often sheltered within larger academic institutions. The Fablab at the Community College of Baltimore County (CCBC) is a member of this international group of MIT offspring, which, as the Fablab website points out, allows you to “walk into a Fab Lab in Russia, [and] be able to do the same things that I can do in Nairobi, Cape Town, Delhi, Amsterdam or Boston Fab Labs.” Fablabs originated as an outreach program at MIT, and their mission still embraces participation and collaboration.

Hackerspaces share this mentality and focus on DIY technology projects, though they are not regulated in any formal way and typically focus more on computers, programming, and electronics. The Baltimore Node, Unallocated Space, Baltimore Hackerspace, and the biologically-focused Baltimore Underground Science Space (BUGSS) represent this group in Charm City.

Innovation Spaces or Incubators, like Betamore in Federal Hill, are another collaborative space for tech projects, though these spaces are focused more on product-design and entrepreneurial business efforts.

Makerspaces, then, are the catchall for any remaining space embracing the ethics of community-based experimentation and making things by hand. Some of these spaces are academic, like (deep breath): dFab at the Maryland Institute College of Art, the Digital Media Center at Johns Hopkins University, NanoLab at the Digital Harbor Foundation’s Tech Center, the Object Lab at Towson University, and the Maryland Design Impact Lab and HCIL Hackerspace, both at the University of Maryland at College Park. There are also non-digital community spaces that nonetheless echo the hands-on approach of the Maker Movement. In Baltimore, luddite Makers should seek out the Baltimore Foundry, Baltimore Free Farm, and the Station North Tool Library for a variety of workshops and opportunities to get your hands dirty (leave a comment if I forgot any).

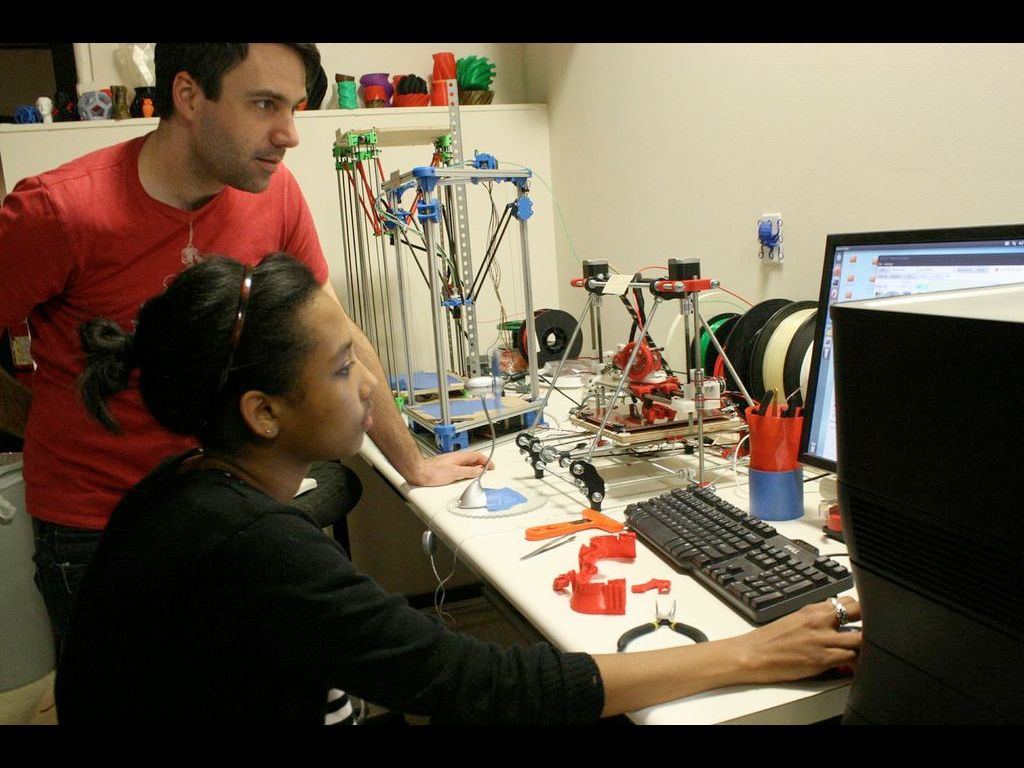

I talked to Matt Barinholz, part of the FutureMakers team that runs NanoLab, about this ecosystem of creativity in Baltimore; he described the overall Maker mentality as being “process based, not a product-based experience.” Those words should sound familiar to artists and their followers, because contemporary art has been embracing process for sixty-odd years. In fact, when I asked Barinholz about the instructors at FutureMakers, he confirmed that “a large number of them are visual artists.” At the same time, Barinholz reminded me that “every fine artist—unless they’re going out and cutting down their own trees for stretchers, and weaving their own cotton for their own canvases—they’re always collaborating with another trade or skill… there are roles that makers play.”

Looking for other voices from the Baltimore Maker community, I turned to Ryan Hoover, who teaches at MICA’s digital fabrication lab (where several of the staff have contributed writing to Make), and addresses issues of digital technology in his own artwork. Hoover described the recent popularity of DIY as “a reprisal of ideas from the 60’s and 70’s, which were in many ways a reprisal of ideas from the Arts and Crafts movement about a century prior to that.” Visual art has a long history of making things by hand, but in recent decades, the field has focused more and more on participation, authorship and ephemerality—ideals reflected in the Maker movement as well. If today’s most forward-thinking artists are collaboratively inventing projects out in the public realm, what separates them from this new movement? Are Makers artists? Are artists Makers?

The answer is probably an unsatisfying shrug. German sculptor Joseph Beuys wrote that “everybody is an artist,” a proclamation that helped define the field of participatory art as the world at large. Residents of Baltimore have seen artwork appear on rowhouse walls, crosswalks, and metro stops— nowhere is safe. The Maker movement, then, seeks to apply a similar creative process to everyone’s relationship to technology and the objects surrounding them.

Hoover voiced some skepticism of this idea, saying that “the idea that ‘everyone is a Maker’ at times rings as a pitch from those who are hoping that everyone is a consumer in the Maker market.” Admitting that “moving people from… ‘consumer’ to ‘maker’ substantially changes the way that they interact with the world,” Hoover is still wary of the emerging Maker industry. He explains that his role as an instructor is to push students towards focused and experimental art-making instead of the “ersatz creativity” that allows Makers to feel fulfilled for following rudimentary tutorials to create “blinking LEDs and [ready-made] 3D prints downloaded from Thingiverse,” adding that “at times the movement seems a little too self-congratulatory because literally anything you make is celebrated.”

Perhaps the term “Maker” is a closer update to “consumer” than “artist,” but let’s prod the relationship a little more. Imagine a Venn diagram joining artists and Makers. If the public associates creativity and hands-on fabrication with making, what is left over in the artist section of the diagram? The classic studio artist might be defined by aesthetics (l’art pour l’art), emotion, philosophy, and internal stories. But more importantly, that artist is probably alone.

I mentioned artist collectives and authorless new media, but most art is still rooted in the genius individual pulling brilliant ideas out of their head in an isolated studio. The Maker movement, on the other hand, has never been anything but a group effort. This sense of community is what really excites Hoover about the movement: “You can get a group of people together working on a common project or pushing each other forward… In these cases there is a different appreciation for the amateur. It’s not a celebration of the mere fact that he or she is doing something. That person is welcomed into the group by members who are excited to share what they know with someone who is interested.” Hoover also advocates for a shift from “Do-It-Yourself” to “Do-It-Yourselves.” Sites like Instructables or Thingiverse encourage Makers to share and remix each other’s projects through shared technology. Virtually every process and project associated with the Maker movement has been documented in multiple online tutorials—can you say the same for the art world?

Comparing artists to Makers helps clarify what art is and isn’t, but the Maker movement could evolve into something very far removed from art. At the White House Maker Faire, President Obama described the movement as “a revolution that’s taking place in American manufacturing—a revolution that can help us create new jobs and industries for decades to come.” Products like the Panono throwable camera or the Structure 3D scanner might have started off as hobbyist inventions, but after these projects and their kin raked in millions through Kickstarter, it’s easy to picture investors with dollar-signs in their eyes leaning closer to the Maker movement. Obama declared June 18th a “National Day of Making,” but it feels more like a desperate grab for American capital than a real appreciation of the movement’s ideals.

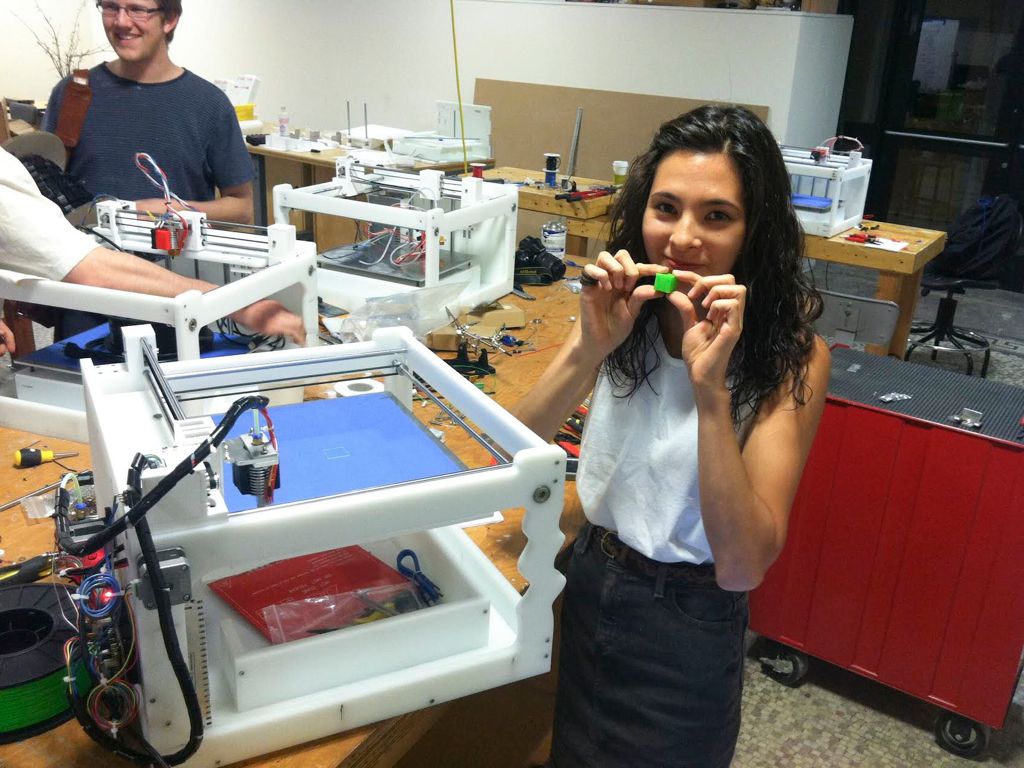

At the end of the day, no matter how futuristic and novel digital fabrication may appear, watching a 3D printer is “just about as exciting as staring at a refrigerator,” according to Barinholz. Gadgets and gizmos will never be more important than learning to think creatively, and that’s something artists do in spades. Barinholz said that “artists are naturally already there,” and that learning “to do the research, thoughtfully compose a concept, and develop a design… that’s where artists and Makers are identical.” Hoover adds that “contrary to popular chatter, these machines do not magically produce your dreams… I always tell students that digital fabrication takes all of the problems you experience working on a computer and multiplies them by all of the problems you have working in the physical world. Fortunately, it also does something similar with possibilities.”

Is it a techno-economic shift when businesses and universities begin to adopt these utopian ideals, or a long awaited victory for the avant garde? “As members of a contemporary democratic society,” Hoover claims, “we have… a moral obligation to be actively involved in the advance of technology. While this is true for everyone, I think it is particularly vital that we have artists who embrace this idea and can provide the vision to help lead us in a positive direction.” Plenty of artists already exemplify the vision of the Maker movement: many love to cook, knit, and craft their lives with the same level of care they invest in their artwork, but there is more to the Makers than just making things with your hands. The movement’s focus on collaboration, democratic access, and interdisciplinary action might offer some tips on how the art world can innovate in its own business of creativity.

Author Benjamin Andrew is an artist and writer currently based in Baltimore. Working with performance, video, and installation (among countless other media) his projects use fictional narratives to create participatory adventures in everyday settings.

* The Featured Image at the top is by Jackie Cadiente (MICA ’13), 3D printed Pinocchio puppet for stop-motion animation. All MICA images courtesy Ryan Hoover.