by Kerr Houston

As we noted in a previous post, the main pavilions of this year’s Venice Biennale are challenging: while not exactly shrill, Okwui Enwezor’s two installations are insistently political, and they offer a pointed attempt to transcend the comfortable clubbishness that often characterizes such shows. (Notably, only half of the featured artists are from North America or Europe, and a full third are women: hardly equality, but surely progress). But of course Enwezor’s pavilions are only the main event: as he notes in an accompanying text, the Biennale can thought of as a garden of disorder, and exploring the dozens of national pavilions, satellite events, and coincidental exhibitions can be a remarkably varied and often richly rewarding experience.

But how, exactly, to winnow or whittle down? While 28 of the national pavilions – many of which were built in identifiably nationalistic idioms in the early 1900s – are clustered together in the cool, shaded Giardini, others take up more temporary and remote residences in palazzi and rented facilities throughout the city. Given the sheer complexity of navigating Venice’s warren-like geography, and the placement a few of the shows on relatively remote islands, visiting all of the affiliated shows is thus a daunting proposition.

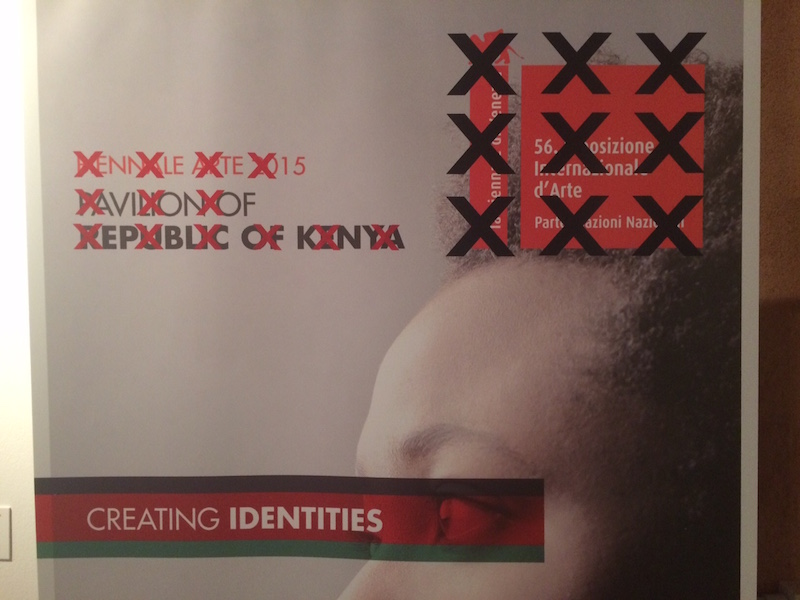

Indeed, it’s especially difficult this summer, for one of the most-talked about pavilions – Christoph Büchel’s Icelandic pavilion, which involved the creation of a mosque – was quickly shuttered by uneasy local authorities. You can visit the building, but the doors are now shut. Then, too, there’s the former Kenyan pavilion, which created waves when its Italian curator invited a host of Chinese artists, raising the specter of neo-imperialism on the African continent and prompting Enwezor’s administration to strip it of its official status. (“A group of unscrupulous artists,” complained Enwezor, “have hijacked Kenya.”) The work is still up, but the accompanying Biennale logo is curtly crossed out, raising a weirdly ontological question: are we or are we not at the Biennale as we peruse it?

Despite all of this, however (or perhaps precisely because of all of this, and the resulting appeal of some sort of scheme or order), each iteration of the Biennale prompts a flurry of top-ten lists, which act at once as a sort of public service and a fanning of critical plumage.

And why should we have to resist the urge to offer our own? If anything, we’ve spent more time walking, and looking, and discussing, than many of the reviewers who breezed through town for the vernissage. What follows, then, is a list of our favorite pavilions and satellite exhibitions at this year’s Biennale, compiled after three weeks of consideration and listed in no particular order, and with no pretense of exhaustiveness.

The Armenian pavilion won the Golden Lion for best national participation, and it certainly deserves the award. Curated by Adelina von Fürstenberg and featuring work by 18 international artists of Armenian descent, the show is evocatively installed throughout the grounds and interior spaces of an active Armenian Catholic monastery. Given, too, that 2015 marks the hundredth anniversary of the advent of the Armenian genocide, a number of the pieces in the show deal with the themes of memory, history, and diaspora: a touching multi-channel video installation by Nina Katchadourian, for instance, traces the efforts of her parents (who are of Finnish and Armenian background) to master each other’s accents with the help of a vocal coach.

But several works in the show also draw meaningfully on the history of the monastery, which was an important printing center for several centuries: Hera Büyüktaşciyan’s haunting Letters from Lost Paradise, for instance, is a rasping, wheezing machine in which long wooden typographic rods rise and fall in sequence, recalling the work of printmakers while also disturbing the silence of the surrounding monastic library. The result is both touching and ominous: a moving, effective elegy to the complex past of an island and a culture.

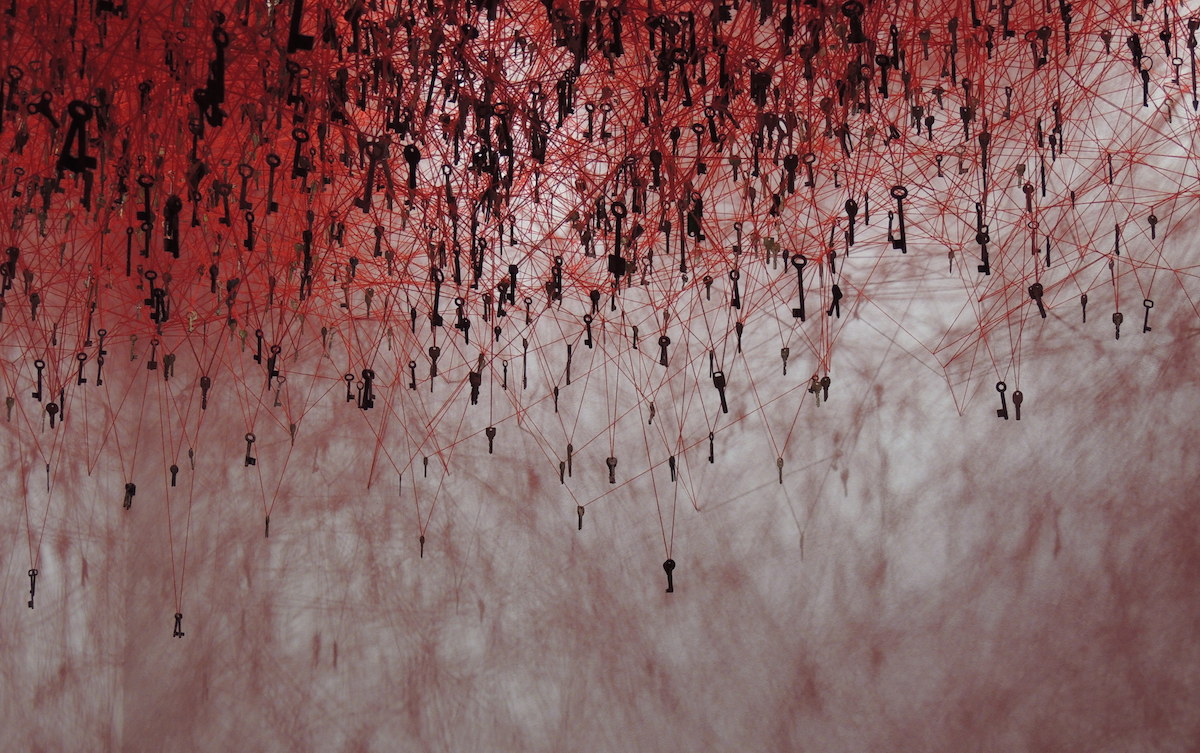

A lyrical, elegiac tone also informs Chiaharu Shiota’s ravishing installation in the Japanese pavilion, back in the Giardini. Dozens of miles of burnt orange yarn are spun in a dense web stretched above two dilapidated wooden rowboats; from the yarn, in turn, hang 180,000 keys, many of which were donated after the artist issued a call for assistance. The boats – abandoned, unseaworthy – inevitably suggest journeys once taken, while the keys evoke possibility and revelation: what doors might these rusting, varied tools have opened?

Admittedly, much of the force of Shiota’s piece lies in its lush scale and visual effect – it is more spectacle, you might say, than critique. And there’s a certain self-promotional quality that surrounds the installation: a time-elapsed video documents the creation of the piece, and free posters at the door feel like advertisements. But the piece itself stands on its own as a rich and poetic transformation of its environment: a dreamscape that leaves one feeling immersed.

A few steps away, in the British pavilion, Sarah Lucas bawdily thumbs her nose at poetry – and hits the mark anyway, with a cheeky installation of frankly sexual sculptural pieces that are at once salty and art historically savvy. Juxtaposed against walls painted in a deep, creamy yellow, some of her pieces recall the work of Franz West in form and scale – but their thick shafts and pendant sacklike forms clearly evoke aging male genitalia, cast in a sagging, mock heroic mode.

A second band of work features plaster casts of female bottom halves, with cigarettes slipped daintily into orifices at various angles. Formally austere, the pieces are in fact complex in their allusions: a witty blend of cool classicism and Surrealist sadomasochism, or of George Segal and back room strip shows. Lucas’ installation seems to have been the most divisive in this year’s Biennale, prompting everything from overt enthusiasm to complete disinterest, but I found its cheerful tawdriness infectious.

But perhaps you prefer high concept to gaudy satyricon? If so, then the Cypriot pavilion, housed in a palazzo near Campo San Samuele, might fit the bill. In a show of deeply cerebral work, Christodoulous Panayiotou offers sophisticated reflections on Cypriot history and archaeology, while also invoking the local setting in a variety of productive ways. In The Price of Copper, a sheet of metal (made from ore mined in the Skouriotissa copper mine, said to be the oldest in the world) acts as an improvised fountain; unaltered but functional, the raw cathode also recalls a sketch by Brecht in which a customer in a music store attempts to buy a trumpet for the mere price of the metal.

In adjacent rooms, Panayiotou presents a series of men’s shoes, produced by hand from material from fake designer handbags purchased from illegal Venetian street vendors. Aspirational knock-offs are thus converted into one-off originals; labor, you might say, redeems the hollow materialism of the copy. Redeems, but also complicates and abstracts – for, as the notes that helpfully accompany the show point out, these shoes will never in fact be worn. Commodity is transmuted into artwork.

On the other hand, the putters at Doug Fishbone’s Leisureland Golf, in the Castello, are meant to be picked up and used. Commissioned by EM15, an organization dedicated to the promotion of the electronic music and digital arts, the miniature golf course is at once creative and bluntly tactile.

Fishbone, a forty-something American artist based in London, invited nine leading artists to design holes; the results are wildly various, and range from irreverently silly to bitingly acidic. In playing a hole conceived by John Akomfrah, one has to putt through the legs of a mannequin of a black man, clothed in a hoodie and kneeling, hands held in the air: the insinuation of possible accompanying violence forms a jarring counterpoint to the trivial routine of miniature golf. Casual entertainment, here, is undone by the specter of racial violence. And that’s just one hole. In the last hole, designed by Ellie Harrison, we aim for a map of Britain, which floats on the surface of an adjacent canal. Almost inevitably, though, our ball caroms off the hard surface, landing awkwardly in the water – rather like, suggests Harrison, the waves of immigrants currently seeking asylum in Europe.

Take your pick, then: from sly political commentary to lush poetic imagery, this Biennale can satisfy various tastes. And yet of course there’s much more on display than I’ve mentioned.

Much of the best work tends towards the spare and the restrained. An elegant show of Finnish glass at the Cini Foundation, for instance, is a ravishing lesson in color, simplicity, and formal inventiveness. Nearby, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Glass Tea House Mondrian, installed last summer as a part of the 2014 architecture biennial, is still on display, and still affecting: hovering above a pool lined with azure tiles, its crisp geometry, refined lines, and synthesis of reflectivity and transparency gracefully marry traditional Japanese ideals and high Modernist architectural dogma.

And let’s also say a good word or two about Camille Norment’s Rapture. A Marylander for most of her life, Norment now lives in Norway, and her installation in the Nordic pavilion – consisting of shattered panes of glass and an ebbing, crystalline soundscape – evokes a certain Scandinavian purity. The result is a contemporary variant of the sublime; one thinks of shifting sheets of ice, of the brittle power of music, and of an ominous, latent violence.

But if such work derives much of its effect from understatement or subtlety, other artists successfully explore and exploit surfeit and spectacle. The German pavilion features a group show that is largely uninspiring – but that does include one of the most notable pieces in this year’s Biennale, Hito Steyerl’s remarkable Factory of the Sun, a relentlessly creative film that simultaneously embraces and spoofs contemporary digital culture. Taking the form, loosely, of a video game tutorial, it is both immersive and critical, delighting in gaudy effects and in the mutability afforded by avatars.

Meanwhile, questions involving identity also inform Halka/Haiti, a striking film screened in the Polish pavilion. The work of C.T. Jasper and Joanna Malinowska, the film documents the staging of an important 19th-century Polish opera, Halka, in a tiny Haitian village that happens to have a small population of residents descended from Polish soldiers. As the singers perform their intricate routines on a dirt road, and a goat idly grazes, villages recline and watch, and we wonder: can such an ornate and artificial form really convey meaning across such a large geographic and temporal gulf?

Ultimately, of course, there’s no easy answer to such a question. Nevertheless, it’s the question that stands at the very heart of an event like the Biennale: what can be communicated across the geographical, cultural and technological chasms that characterize contemporary life? How and why does some art move us, or leave us wanting more?

And so we move from pavilion to pavilion, strolling through a garden of disorder: attentive to the myriad species on display and aware of the fact that the ones that catch our eye likely say as much about us as about their own underlying logic.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.