Jermaine Bell in Conversation with Devin Allen

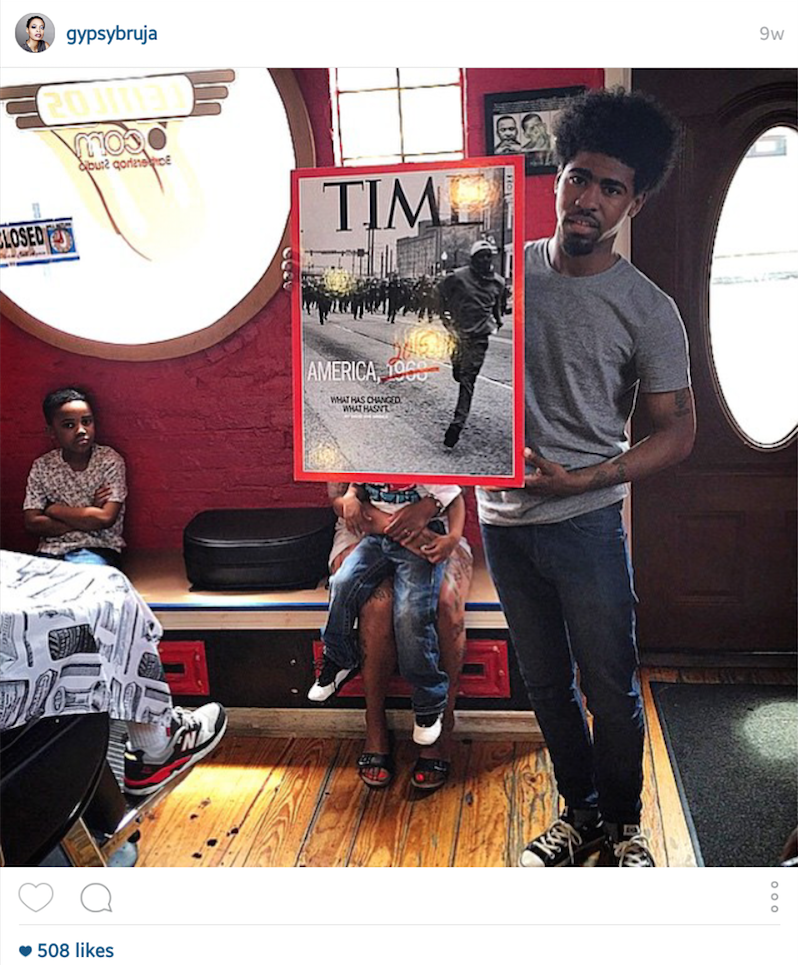

Devin Allen or #bydvnlln, as he is known on Instagram, went from being a guy who worked the graveyard shift at a facility for intellectually disabled people to the cover photographer of the weekly news bible, Time Magazine. I had seen his photo every five minutes in my Facebook timeline during the weekend before the now infamous CVS burning in Baltimore, and assumed that it was just another polished Reuters’ image, until an article showed up stating that 26-year-old Baltimorean Devin Allen took the photo.

Who was this mystery photographer? Only those close to him knew what he actually looked like. Like most people, I first saw him via an image by Trae Harris that went viral, taken at a private party celebrating his cover. A lanky guy with a big afro in a simple gray t-shirt, jeans, and sneakers. Its only been two months since Devin became a celebrity, and I wanted to know what it all means and feels like to him.

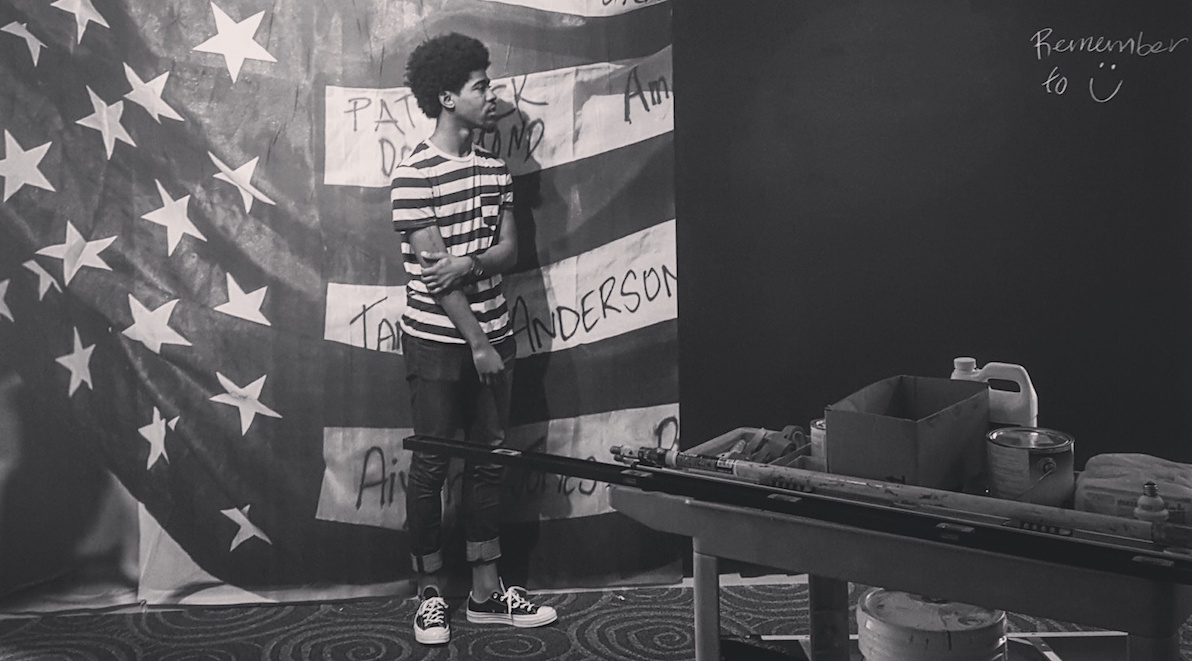

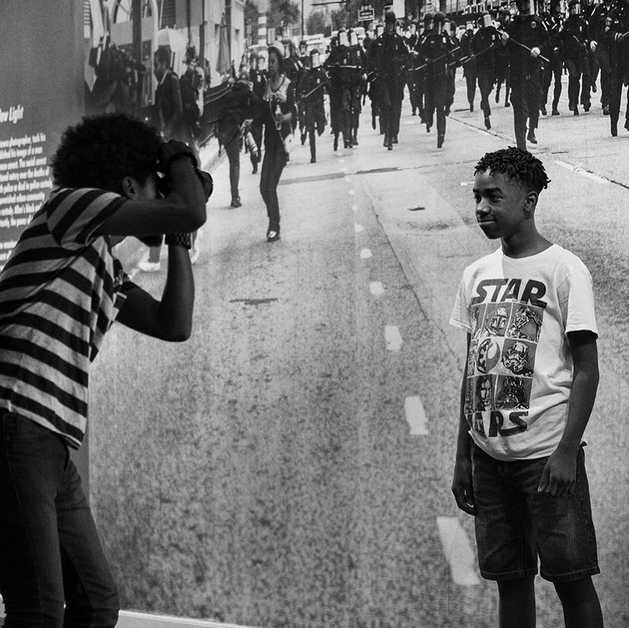

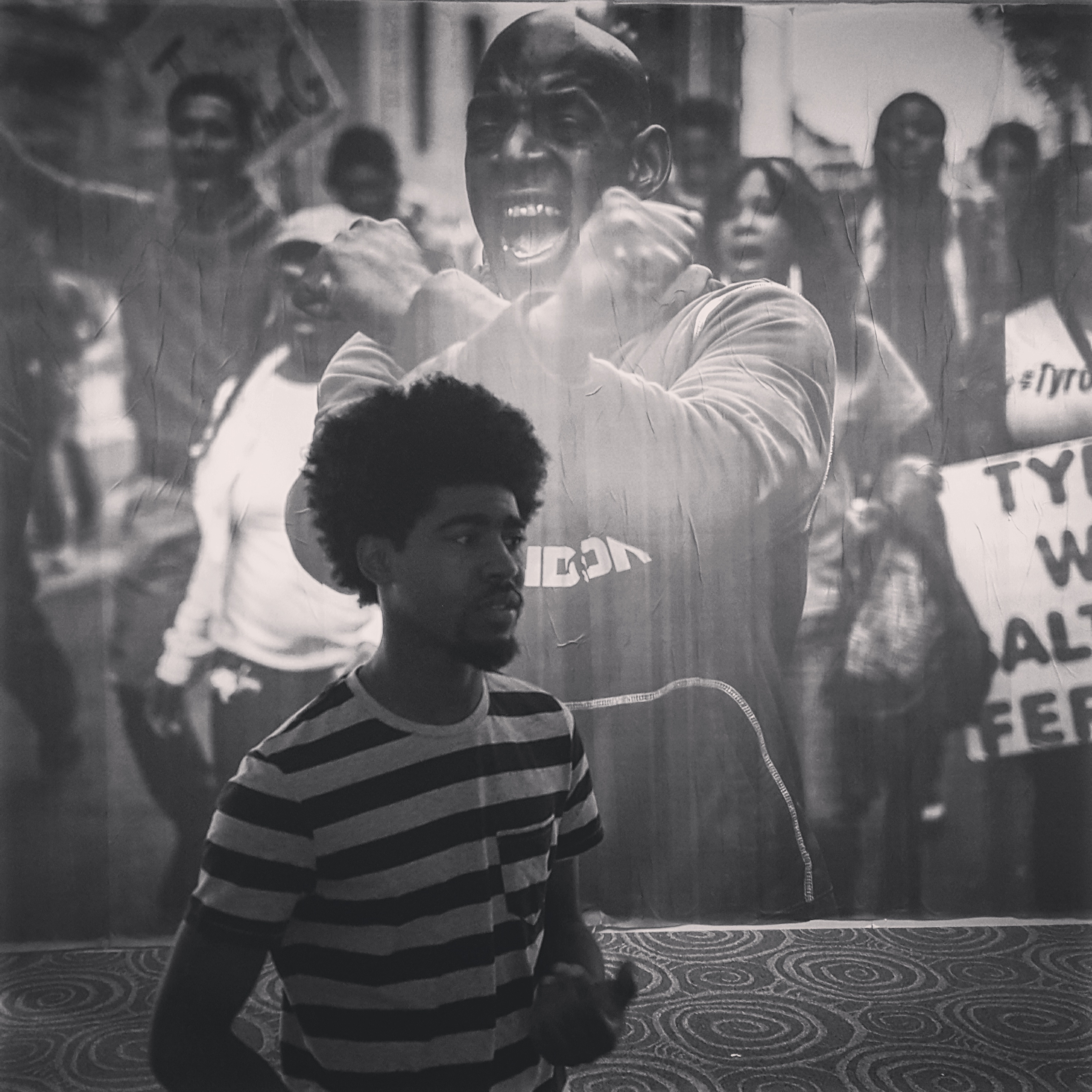

The following is part of my conversation with Allen, in conjunction with his new exhibit at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum.

JB: I understand that you grew up in both Baltimore City and Baltimore County.

DA: I spent most of my time in the city but I lived out in the county, too. I went to a Baltimore city school and a Baltimore county school. I went to Forest Park High School and I went to Woodlawn. I spent most of my time hanging in the Garrison area, in Edmondson Village, Yale Heights, and Irvington with friends… basically all of West Baltimore. But, I had friends all over Baltimore. I was one of those people that you could see here or there. I wasn’t one of those people like “this is my hood I stay here.” I had no loyalty to one neighborhood. I was a really social person growing up.

I had a good family foundation. I was spoiled not materially but lovingly. I had four aunts, and all of my immediate family comes from these four women. We’re really close knit. Once you come around two or three times you are family. It was also tough because I watched a lot of people pass away. I watched twenty or more people die in my 27 years. And, about 10 were really close to me. I have seen people get killed; I have even been shot at before. We recently lost one of my aunts last year, which was really heartbreaking for my family.

My family has supported me and helped me be whatever I wanted to be. I wanted to be Allen Iverson so I played basketball, at one point I wanted to be a Ninja Turtle… I took Karate and wanted to be Bruce Lee… I even wanted to be Sammy Sosa and played baseball. So, I was able to do a lot of things the average kid in Baltimore City wasn’t able to do, even though I was hanging around drug dealers and killers. I had to kinda distance my self from two of my close friends that I lost because I was pursuing art. And that’s why everything that is happening now is so important to me.

JB: So the matriarchs in your family were a cornerstone for you, that’s a common theme in Baltimore City it seems. Can you speak more about how significant your mom and aunts are in your life?

DA: Family is EVERYTHING to me! I just did a short series over the 4th of July weekend about the Black Family Cookout. Because all black families have a lot of similar issues but the world doesn’t see how tight we actually are. In my family there are a lot of women, not as much men, and the women are strong. My father was in and out of my life but that NEVER slowed my mother down. She put it all on the line for me and my little sister. My grandmother lost her husband because he was sick and she was left with two kids, never slowed her down. Her sister had trials and tribulations but that never stopped her from raising her kids. We’re all like one big unit. You fight one you fight all of us!

My mother was amazing because she kept it real. She would say, “Don’t smoke weed because I used to back in the day and it’s not good for you.” She didn’t hide things from me. A lot of bad things that happened to me is because of my own stupidity because she had already told me about it. My aunt Joan was the fun aunt, she was tough too, but I could snatch her wig off and give her wet willies and not get in trouble. By the way this is the kind of stuff that happened last year, I am 26 years old snatching off my aunt’s wig. She always told me I was going to be great and she passed way last September. I just wish that she was here to see this. She had two sons and a daughter that are like my big sister. And my uncle was like my father, and I have an amazing stepfather so my family is tight! I could go on all day.

JB: What’s so funny is that I was following the hashtag #CookoutNewsNetwork along with your black Family Cookout series, and its crazy to think how much black families universally have in common, and even the name “cookout” is universal in our community as opposed to “barbecue” which its typically called.

DA: Yeah! We all have similarities in our families though. But, that’s the thing, though, the way media and people view us… They don’t understand how tight the black community actually is. We have our faults but people don’t know how we break our backs for people in our families. And, that’s why I gave people a glimpse into my private life with that series, but I would go to one of my friends and it would be the same set up. We all have that cousin that’ll pack up a plate to go before we all even eat!

JB: {laughter} Tell me about your transition from high school into “adulthood.” And, a lot of people struggle, particularly black people, because a lot of times college isn’t an option for a lot of black kids.

DA: It was difficult. But, I made it difficult. I put myself in scenarios I shouldn’t have. My issue was that I was a follower. I had a mind of my own but I lost that when I went to high school. In middle school I was in Art GT (gifted and talented) and I was small so I was picked on. I lost my mind when I went to high school I fought. You couldn’t say anything negative to me without me punching you in the mouth. I had a Napoleon complex. I was more concerned about girls and being fresh so I always did the bare minimum just to pass. I never went to junior or senior prom because I wasn’t allowed to because of fighting. I transferred from a city school to a county school and the curriculum was different.

In twelfth grade a lot of my homeboys were coming to class with Pradas on their feet making hundreds of dollars a day. So after high school I tried the school thing. I went to community college for sports medicine but that’s when I found out I had a daughter on the way. In 2007, a year after graduating high school I totaled a car and was put on bed rest. It’s sad but a lot of my friends said, “We never gonna make it past 21.” That’s just how we thought. Because when I was growing up there were like 300 murders a year, and Baltimore is small.

I didn’t really find myself until I had my daughter. Then I knew I couldn’t just live for myself and do some of the things that I was doing. My daughter inspired me to rush and become a man. So, I took a break and went and got a job in corporate America at Trans America Agon Monumental Life for three years and I learned a lot, I found out that it was boring as hell and that it was not for me. And, I got laid off so I started a poetry night with a good friend of mine at Amour (1116 Hollins St) in South Baltimore and Carribean Paradise on Charles St. We’d also do vendor days where people who sold jewelry and art could sell their stuff…

JB: So your entrepreneurship was always tied to the arts…

DA: Yup, I also did an event called “Art, Wine & Worries” with my friends Josh and Davin: It was art and wine and spoken word. That was a huge success. That was the first time that I let people see my work in person. Art saved my life! And that’s why every shot is important to me. That’s why I do it everyday. I am going to be a photographer and that’s why I resigned from my job recently to pursue this.

JB: When I first met you at the Creative Morning you were still working ovenights right? That’s a done deal?

DA: Yeah, I worked overnight working with people who had intellectual disabilities and autism. I loved those guys; I worked there with the same guys for two years. But, It was tough working from midnight to eight AM, and then I would go protest, plus the interviews with the media. I was fatigued. My mother was like, “I got you, don’t worry about your bills.” And now I can dive into my work. I would have never gotten as far with this exhibit if I were still working.

JB: As a black artist that went to an art institution, when I began interviewing for jobs I saw that were not that many black people in positions of power in the arts. With your talent and a great opportunity presented to you, you were able to avoid all of this. How do you feel about that?

DA: I just found this out recently and it’s sad! I think a lot of black artists may have the talent but don’t have the resources to find and define themselves through their art.

JB: Well, like you said earlier, there is a big difference between the Baltimore City and County cirriculum.

DA: When I went to school you had to take two art classes to graduate. I played the clarinet and I sucked! But you had to take these classes. It’s different today–the kids today are not required to do it. They are being told to be a CNA / GNA or a CO if you’re a female, and be an athlete if you’re a boy, because people are chasing money.

And, in Baltimore we are very materialistic and in the art world a lot of times you’re not going to get the money up front. You’re not going to make thousands of dollars. You’re not going to be able to pay some of your bills if you chase art–you have to be willing to make those sacrifices but, then at the same, time look at the living conditions in Baltimore. You can’t make those sacrifices if you don’t have those tools and you have to network and Baltimore is a hard city to network in because we do NOT cross those cultural lines.

I know some amazing black artists that will never go and work with people at MICA or other institutions. You don’t have to, but I hang with different people in different neighborhoods. It’s where I get my inspiration. I had to go find friends in Station North, Mt. Vernon, wherever… and not worry about if the person was white. So, it’s on both sides of the fence. And, these people have added to my growth. And what happens in our culture is that most people only shoot one thing. I shoot everything. At the CreativeMornings event you saw the diversity in the crowd. But, another black artist won’t get that. I think in the art world I can play a part and help close those cultural gaps.

JB: That brings me to my next question. Do you think that you could have gotten this far in Baltimore w/o the Time cover?

DA: I think so! I don’t think I could have gotten here this fast, but when I first started taking these photos I had 10,000 followers on Instagram and 5,000 on Twitter. That’s why I used the Twitter and didn’t reach back out to the local media. I used my own platform. And, I would have never made it to Time without my platform. But, my platform was built.

JB: Let me clarify that question. Because maybe it was insulting, and I didn’t see it until I said it. Do you think Joe Schmo from Edmondson Avenue could walk into a local publication and penetrate the majority white art scene?

DA: No, that’s why I didn’t do it! And, I tried that already! When you’re doing art you have to have the same mentality that you have when you are on the street. I implement that in my art. I have loyalty and respect. I wont sell myself out and I am loyal to who I work with. That’s what got me here. The Time picture isn’t the best picture and it’s not my favorite one. But the people at Time heard my story and I didn’t try to hide my past–that’s what also helped me get the Time cover. If I weren’t from Baltimore, if I was just someone who came here to document the riots, I would not have gotten the cover.

JB: You could easily move on, and with all of these barriers here, why do you stay?

DA: I was going to move to New York and pursue photography because of those barriers. But, I have all that now, and I could’ve left. I didn’t have to do the Reginald F. Lewis Museum Exhibit. I have been to the Look 3 Festival and met amazing people National Geographic and the New York Times; I have met the people from Instagram. But, what would that fix? The barriers would still be here for others once I left. So, now it’s time to bust down those barriers for everyone else.

What if I knock these barriers down and they are built right back up? I can’t let that happen. At the end of the day I am a father and my daughter will more than likely grow up here. Therefore, if I don’t break these barriers down she and her friends will be going through the same things that I went through. A lot of people get to a certain level and leave.

I’m tired of people complaining about what you can’t do in Baltimore, but you’re not trying to change anything! You get your attention on social media and then you leave. And even if they don’t leave, you’re not helping the next person get to that next level. You’re not spreading the love and that’s the issue! In other cities my artist friends have friends of all kinds. You might have your pockets, but people still cross paths. In Baltimore you walk past each other and don’t speak. It doesn’t have to be like this.

If I am a black artist and you’re a white artist, we can teach each other something. You might have the formal training, but lack the intensity of a street artist.

I don’t know everything about lighting, and there’s nothing wrong with getting a piece of paper that says you have the talent. I just think you need both!

JB: So now that you have all of this success do you see yourself going back to get a degree?

DA: When everything kinda dies down and I have some time to myself, maybe not full time but taking some business classes to learn that aspect of art. Let me stop and say this: I am getting some AMAZING help. I have already broken a lot of barriers here already. Because a lot of the people I am getting help from are people I didn’t even know existed, but they have given me some good advice and great resources. I don’t want to be one of those people who have a ton of staff and then wind up being arrested for tax fraud because I didn’t handle it myself. I want to know about everything that involves my art. I love photography but I also want to learn how to do sculpture. I love art in general, so I may take some workshops and things like that too.

A photo posted by Devin Allen (@bydvnlln) on Jul 5, 2015

JB: So now that some of the sexiness of Baltimore has gone away with the protests. Is that bad or good for your work? I see that you are exploring other things with The Black Cookout Series.

DA: I have an eye for everything! You can’t put me in a box. But right now as an artist I had to put myself in a box because of the protests. I took a break from shooting models. Right now I can’t be selfish. I have also been taking pictures of vacant homes, when the homeless people were removed from MLK, me and Kwame were there. I feel obligated. And we both gained attention from the negative protests so we have to do something positive with it.

JB: Yeah, its sad it took nine lives to bring down the confederate flag. And your great talent was realized during this horrific event; the death of Freddie Gray. Do you ever feel bad about that?

DA: Of course, nobody wants to build their career off of the death of another human. It’s sad because at the end of the day I could have been Freddie Gray. People always want to talk about this backstory. People were fussing on one of my pictures saying, “He was a drug dealer.” The law states that he deserved the right to a fair trial, and he didn’t get that. WE haven’t been getting that and its not fair…

JB: And, he was guy of your size, like you said, small.

DA: He wasn’t a guy that was like six foot nine.

JB: It wasn’t like Eric Garner or Mike Brown or even some one like my size because that’s what you always hear, “He was large and frightening” like Godzilla or something!

DA: That’s why I think my pictures are important because that’s how some people look at black people. People are raised to fear us. They still treat us like animals; wild, untamed animals and forget that we are human. You can walk by us everyday and yet when someone is slain and you’re so cold. The CVS is more important than losing a life. My life isn’t more important than the next person’s life. I don’t care what your skin tone is. We are all the same. We have a heartbeat, families, and we all have feelings. That’s why I have to work with the youth and teach them photography because we have to come together. And, since Freddie Gray’s death the crime rate has risen. We fight for justice for his death and yet we kill each other. So many things have to be done and I can help with photography.

JB: On the fouth of July I got stuck on the grill and I overheard my uncle preaching “today there is no unity amongst black people, back in my day…” But, its true, I look at Soul Train and see how much we invested in ourselves. Today the music is telling you to consume, to sell drugs, to be misogynists, everything except love one another… What sparks that revolutionary spirit in you?

DA: I really don’t know, my mother says I always had it in me, but I don’t know… When I was spending time trying to find myself I read a lot. I got into different things, I started meditating and became a very spiritual person, not religious but spiritual. And, with researching, you learn so much that angers you that you didn’t know before. I studied a lot about what black people used to be. Even if you look at my old work I was all about empowering our women. And, I have a great respect for my mother, which the entertainment industry doesn’t do. And, I look at how we were kings and queens, we were then forced into slavery, we started to get somewhere in the 60’s and 70’s and then crack, AIDS, heroin …

JB: Reagan…

DA: Right (laughter)… All of these things that affected the black community.

JB: Bush(s)..

DA: Yes!! And we are still here! But, I don’t know if we have become content… I just watched the Nina Simone documentary, and that relit a flame in me! I’m gonna go harder now!

JB: GREAT FILM!

DA: You never heard about Nina Simone or Huey Newton and the black panthers during black history month in school–you only heard “ I have a dream.”

JB: Well, I think in the most pivotal scene in that documentary she was in African garb, and braids, in front of some groovy 70’s art, so it can be framed so many ways like “she is crazy” when really all she was saying in that scene is “if I am backed into a corner I will kill for my life.”

DA: She was too strong! When you’re strong like her they want to silence you or pay you off and bring you to their side. There was a slew of images of black people: Sanford & Son, Good Times, Family Matters, Fresh Prince, Martin black families… Now what do we have? Reality tv?!

JB: Love & Hip Hop.

DA: I feel like we are taking steps back. We forgot because after civil rights we were free physically. But, mentally we were enslaved. Hip hop used to be a vehicle for expression. Even like Gil Scott Heron they talked about issues. Selling drugs is positive, killing another man is positive now; it doesn’t make any sense to me. It starts with self-love. People take issue with “Black Lives Matter”– whats the issue? Its self-love!

JB: And that’s what Nina was saying: I love me! Especially since no one else will!

DA: Right and what she went through as an artist is something that I am sure I will have to go through myself. I can go get a freelance job and take off and forget what I fought for or I can take the tough road and do what I am doing now. I do want to be a photojournalist and document this struggle, but I want to show people that I can do other things!

JB: Well, it’s a double-edged sword. I find myself gravitating towards black artists at Bmore Art because I want them to be heard, but that doesn’t mean I don’t love the other parts of the art scene in Baltimore, its just kind of a calling right?

DA: It definitely is! A lot of it is prejudging. When I first started doing this I didn’t get a lot of support from my peers and Baltimore. A lot of people made fun of me because I went from being a dude with gold in his mouth and braids to wearing skinny jeans and taking photos. At the end of the day I didn’t care because I was happy! You have to take the time to find yourself. If you would have told me four years ago I would be who I am now I would have laughed.

JB: So what’s it like to be in front of the cameras now, because you famous! I am going to need a photo for the story too.

DA: Its weird, once I started taking photos I deleted every picture of myself from the internet. Its sad, but I did not want to be pre-judged, I wanted people to just look at the art. I didn’t want you to look at me and get caught up in what I dressed and looked like. I didn’t want the limelight. You didn’t start seeing pictures of me until I started doing interviews and then I was like, well the cats out of the bag. I don’t like posing for pictures–I suck at it. I am a quiet person and I used to be able to walk down the street and take pictures now people are like, “I know you.”

JB: Now it could be that some one takes a photo of you taking a photo. That’s meta, right?

DA: Now people ask about my bush, “Whats up with the bush?” I wear the same thing–black and gray everyday and jeans. Every moment is not a photo op of “Look what I am wearing.” And that’s why The Awakenings and the new Light is so important to me. Is just about that. This Freddie Gray situation woke people up from the matrix. You also see Baltimore in a new light. I took one picture of the CVS because I saw some guys taking selfies and photos in front of it. They didn’t come to support, just to be tourists. And seeing the damage

JB: Cultural Tourists… How does it feel to have your work that’s so insular, you know black life on a larger platform.

DA: I love it. I get people writing in foreign languages on my page saying they can relate because its what is happening to them and they can relate!

JB: You own being a Black Baltimorean, which isn’t typically the sexiest thing to be. What do you want people to know about you?

DA: I want people to know that they can tweet me. The Instagram thing is kinda crazy because there are so many comments. I want to comment back though! Don’t treat me like I am P. Diddy! I am a typical guy! When I go to festivals there aren’t a lot of black photojournalists there. I would say 5-6 out of three hundred people. And, I am willing to be that guy that is not getting paid and working hard so that the photographers that comes behind me can have better.

Author Jermaine Bell is a Baltimore-based Graphic Designer and Writer.