A Review by Kerr Houston

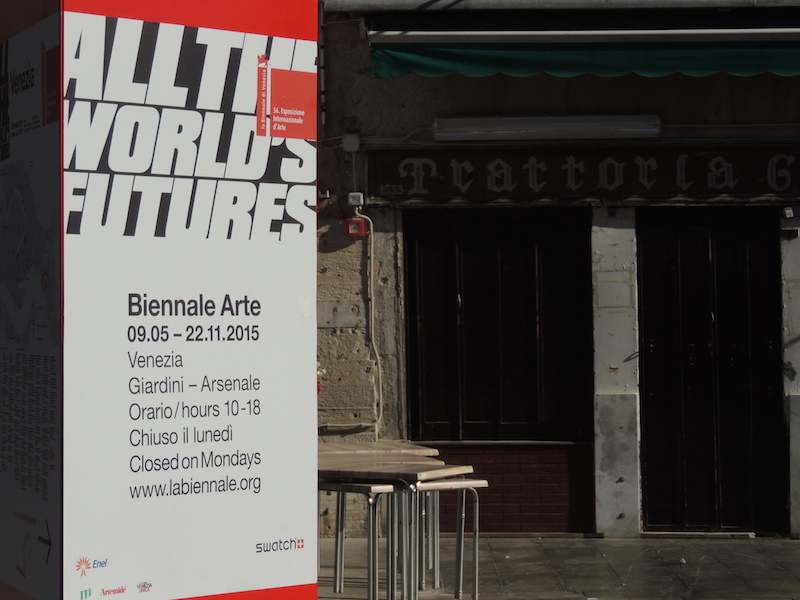

Taking in the Venice Biennale is never exactly easy. The sheer scale of the event – the oldest and largest regular exhibition of contemporary art in the world – and the diversity of the work on display ensure that. But this year’s version, which is curated by Okwui Enwezor and cheekily entitled All the World’s Futures, is particularly demanding. Characterized by an insistently grim mood and labeled in a fashion that does the viewer few favors, this Biennale offers all of the warmth of a sermon by Savonarola. It’s been characterized variously by critics as a glum trudge, as shadowy and sepulchral, and as morose and conceptually bewildering: regardless of the label that you choose, though, there’s no doubt that it’s an especially challenging show.

Of course, that’s by design: these are, this show proposes, dire times. Sea levels are rising, workers around the globe are being exploited, and individual rights trampled. And so we’re greeted, at both of the exhibition’s primary entrances, in a bleak and ominous fashion. Stroll towards the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, and you’re met by a heavy veil of pendant black banners by Oscar Murillo and a portentous neon inscription by Glenn Ligon (bruise/blood/blues) and, once inside, by a series of drawings by Fabio Mauri that repeatedly emphasize the words The End.

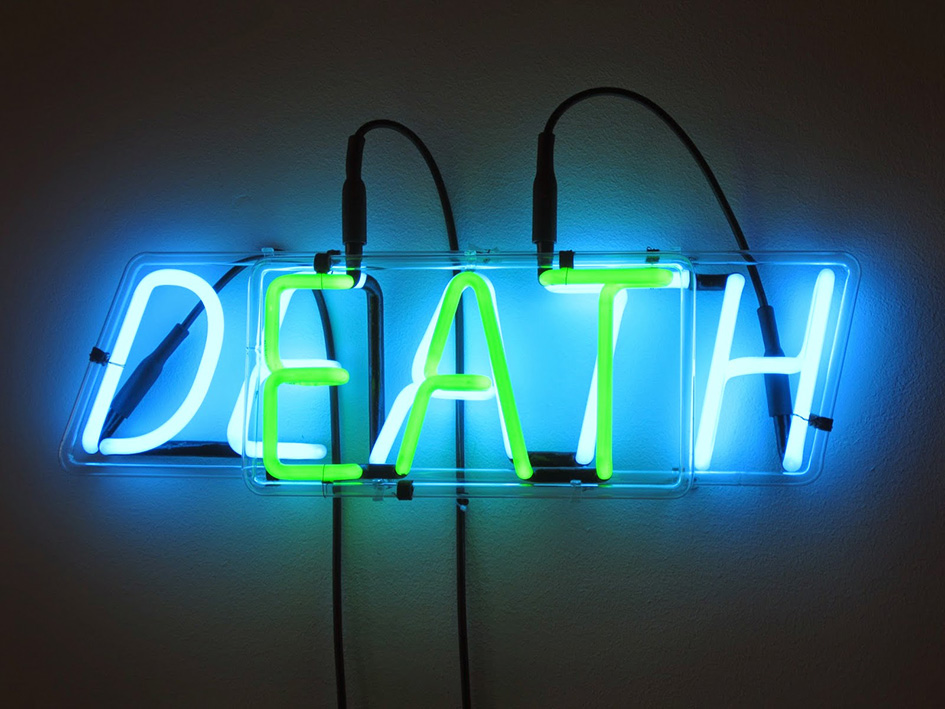

The opening room of the Arsenale, meanwhile, features a row of sputtering, flickering bulbs by Philippe Parreno, a flashing neon sign by Bruce Nauman that alternately reads Eat and Death, and numerous, prickly bouquets of blades by Adel Abdessemed. No doubt about it: this is a show composed in a minor key. The world’s futures, it seems, are dismal.

For the most part, however, this Biennale seems preoccupied with specifically socioeconomic forces. If we leave the many national pavilions and satellite exhibitions aside for the moment, and focus on the two pavilions curated by Enwezor, the emphasis is particularly notable: a remarkable number of the works allude to the flow of capital in the deregulated, neoliberal contemporary economic landscape.

Taryn Simon recreates the bouquets featured alongside world leaders in a series of diplomatic ceremonies, revealing in the process that the juxtapositions of geographically diverse blooms are only made possible by air freight. In a video by Maja Bajevic, floor workers in a decaying Serbian carpet factory sing an archly ironic oratorio about fluctuations in the prices of staples such as coffee and rice. And Andreas Gursky’s densely detailed photographs offer a cool, gelid look at the trading floors of several stock markets, in which the individual traders appear as mere cogs in a much larger machine.

But the largely frictionless movement of goods and capital is hardly, this show further insists, without its costs. Indeed, the conceptual centerpiece of this year’s exhibition is a live reading, in 20-minute segments performed four times a day, of Capital, in which Marx famously argues that capitalism ultimately rests upon the exploitation of laborers, whose work results in surplus value and in corporate profit. In turn, a number of the works in the show represent extensions of that central theme.

Most obviously, Isaac Julien’s 31-minute film Kapital documents a conversation between the filmmaker and the Marxist sociologist David Harvey. But other works also investigate the darker sides of capitalism. A banner fabricated by the Gulf Labor Coalition urges attention to the violation of worker’s rights in the construction of Abu Dhabi’s new cultural facilities. Perhaps most haunting, though, is Jeremy Deller’s Motorola WT4000, a computerized armpiece employed by Amazon in order to gauge the efficiency of its workers. No alteration or intervention is necessary on Deller’s part; the object, by itself, testifies to the ways in which the sleek and superficially frictionless global economy rests upon the objectification of physical human effort.

Okay, then: point taken. But despite the earnest and often moving aspect of such works, the show is hobbled by a number of factors. For one thing, it feels rather formulaic. Indeed, the exhibition is an almost perfect illustration of a pattern identified a couple of years ago by Grant Kester; that model revolves around, in his words, the twin concepts of “the viewer who enters the gallery space to be confronted by a work that challenges his or her normative assumptions about the world, and the artist who possesses a singular ability to recognize and lay bare the hidden ideological devices which govern our routine lives without our knowledge.” Thus, Petra Bauer’s projected photographs of early 20th-century women’s socialist groups imply a revelatory quality: the histories of labor and resistance are being resurrected.

But do the histories and workings of capitalism really need, here and now, to be laid bare? As Kester points out, the very assumption that they do assumes a hypothetically ignorant viewer. And yet any visitor to Venice who has read even a jot of history will be entirely aware of the long and fraught relationship between mass production and exploitation.

Indeed, the Arsenale – once Venice’s massive shipbuilding facility – was the site of one of the world’s first assembly lines: a fact accented 700 years ago by Dante, who referred to the factory workers smearing vessels with pitch in describing a circle of hell. And then, too, there was Ruskin, the great 19th-century critic, social reformer, and lover of Venice. When he visited Murano, and saw local glass-makers tethered to machines that spat out glass beads, he was outraged:

Glass beads are utterly unnecessary, and there is no design or thought employed in their manufacture… The men who chop up the rods sit at their work all day, their hands vibrating with a perpetual and exquisitely timed palsy, and the beads dropping beneath their vibration like hail… Every young lady, therefore, who buys glass beads is engaged in the slave trade.

Thus, while the form of protest may have changed, the basic message is hardly new, and the implicit thesis of this year’s Biennale ultimately feels less pressing than historically unaware.

Or even naïve, for there’s an ideological simplicity to certain patterns in the installation. As Andrew Russeth has noted, for instance, it’s hard to miss the attention paid to the hands of workers in several of the more socially minded pieces. In Hiwa K’s The Bell, metalworkers melt debris from the battlefields of Iraq, and recast it as a bell; meanwhile, in Steve McQueen’s Ashes, we watch as hands tenderly paint and prepare the burial place of a young fisherman. Similarly, active hands regularly punctuate Joachim Schönfeldt’s The Guilds and Unions, an examination of craftsmen and work spaces in Johannesburg.

These are all fine pieces of art, on both formal and conceptual levels, but in the context of this year’s Biennale they read as reductive. Can the vast and systematic wrongs of capitalism really be remedied through tender, local manual labor and a respect for craft? It’s as if Enwezor has curled up with Matthew Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft and a warm cup of tea.

Perhaps even more embarrassing, though, is the inefficacy of the art that does try to be, in some way, meaningfully productive or dialogic. You may have heard, for instance, of the flap that surrounded Christoph Büchel’s The Mosque, in which the artist converted an unused Venetian church into a working mosque – or, as the space began to attract local Muslims and curious tourists and thus unnerved local municipal authorities, a ‘mosque-like space.’ Ultimately, the wording didn’t matter: the building was closed, and nothing remains but a dour legal notice. Similarly, Carsten Höller surely had good intentions in installing a continuous, slow-moving carousel ride outside the Giardini – but the device was apparently not up to code, and thus slowly goes round and round without a single rider upon it. The effect is plaintive, and the larger implication worrisome. For if artists can’t even mount a temporary participatory work, it’s hard to imagine that they can successfully forge an alternative to global capitalism.

Indeed, you might even argue that the primary lesson of this year’s Biennale is that even nominal challenges to capitalism are easily folded into the larger logic of that very system. That’s a familiar argument, sure, but it’s on clear display throughout Venice this summer.

Even as Isaac Julien explores Marxist critiques of capitalism with David Harvey, in the Giardini, his work is featured elsewhere in the city in a collaboration with Rolls-Royce. Even as Enwezor offers an emphatically diverse roster of artists, those artists embody, in their own peripatetic careers, the mobility central to neoliberal capitalism (Elena Damiani was born in Peru, but lives and works in Copenhagen; Samson Kambalu was born in Malawi, but lives and works in London). And finally, even as Marx explains, in the text that is the spiritual core of this show, how differences between labor value, use value, and exchange value line the pockets of industrialists, gallerists freshly arrived from Art Basel head to the Giardini and promptly inflate the exchange value of the works on display.

As an argument, then, Enwezor’s Biennale might be said to be undermined by a host of unresolved tensions. (Andrea Fraser’s “L’1 %, C’est Moi” remains a more honest and bracing look at the intersection of global capitalism and contemporary art). But the Biennale, of course, is not merely an argument; it’s also an exhibition of art – and, happily, a good deal of that art is worth looking at closely on its own terms.

Perhaps the most popular piece in the Giardini is John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea, a lush, seductive film that unfolds on three screens and that combines archival imagery and newly shot footage in crafting what is at once a paean to the ocean and an unsettling visual essay. Accompanied by an ethereal soundtrack and a spare voiceover, it would feel at home in an IMAX theater, and yet draws on a variety of visual and literary sources in crafting a bittersweet ode to a threatened resource.

Utterly different in feel and form are sixteen short films by Kambalu. Clearly inspired by the formal simplicity and modest scale of early silent cinema, Kambalu assigns himself rote and often tongue-in-cheek tasks – holding up a leaning tree, or using an ATM – and then shoots them brief black and white sequences, using a static camera. Subsequently, however, he edits the footage so that it often flickers backward, allowing him to investigate the basic temporal properties of film while also offering a playful tribute to pioneers such as the Lumière brothers, or Buster Keaton.

I was also struck by Adel Abdessemed’s Also sprach Allah, a rough carpet on which the artist scrawled the titular phrase while being tossed upwards by a group of men in white shirts (an adjacent television documents the action). Yes, the reference to Nietzsche may feel a bit forced, and the allusion to a flying carpet perfunctory. But the image of the airborne artist scrawling hurried fragments of the text even as he succumbs, again, to gravity is an appealing and poetic emblem of prophecy and revelation.

This show also has something to offer both committed formalists and no-nonsense literalists. Four pieces by the Argentinian Eduardo Basualdo offer striking manipulations of utterly conventional objects: a door, a desk, and – in perhaps the strongest piece, Grido – pieces of paper that are marked with graphite and then forcibly compressed, resulting in a jagged, nervous line. The result is at once simple, freshly inventive, and unsettling in its insinuation of a latent violence. Meanwhile, violence of a different sort – institutional, rather than physical – is the subject of Im Heung-soon’s terrific Factory Complex, a documentary film devoted to the examination of poor labor conditions experienced by women in a variety of South Korean workplaces. Juxtaposed with clean, classically composed shots of call centers and storerooms, a series of anecdotes culled from interviews (which focus largely on physical and psychological duress) are simply piercing.

Although shot through with moments of beauty, then, this is far from a lush or seductive exhibition. There’s little to no sensuality, and when flesh does appear, it is often under duress, or disciplined. The lyrical nudes and pastorals of Titian and Giorgione thus feel especially remote in this corner of Venice, as Enwezor encourages us to think instead about a variety of forces that constrain, delimit, or corrupt. And yet, perhaps all is not bleak.

This year, Adrian Piper was given a Golden Lion, and she is represented in part by a piece in which a single phrase – Everything will be taken away – is written repeatedly on four chalkboards, in the manner of a schoolroom punishment. The phrase is ominous, discomfiting, and almost eschatological, and its form obsessive. Strikingly, however, its inspiration lies in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s famous declaration that “Once you have taken everything away from a man, he is no longer in your power. He is free.”

The 56th Venice Biennale is pointed, didactic, and challenging. It feels at times adolescent, in that it evinces an active distaste for the current form of the world and yet succumbs to the very forces that it decries. Despite its shrillness, though, it stands as an exceptionally diverse show, in terms of both artists and media.

In November, inevitably, everything will be taken away: the artwork packed and shipped, the gallery halls empty. But for now, visitors to Venice are free to explore Enwezor’s dark vision of the world’s futures – and free to emerge, as Dante once did, after thinking of the Arsenale, into the sun, and the other stars.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.