Stephanie Barber revisits her solo In the Jungle performance as a collaborative endeavor

By Bret McCabe

Stephanie Barber is learning how to let go. It’s not easy, and it’s not the first time. The local artist, filmmaker, musician, and writer notes that we’ve all had to learn how to let go in our lives.

“You know when babies are first born and they’ll hold your hair?—that is really easy,” Barber says, making her hand a fist as if clutching invisible strands of hair, an illustration of the Palmar reflex with which we’re all born. “But this,” she continues, unclenching her hand, “is a complicated motion. So when you’re asking a baby, ‘Please let go,’ they’re like, Lady, I’m trying. So part of me has been trying to build that muscle—the letting go.”

What she’s learning how to let go of is her own work, to let collaborators in and inhabit it. She’s currently both shooting a film and rehearsing a new staged version of her 2009 solo performance In the Jungle, originally commissioned as a sound piece to be performed at the Stone in New York. She prepared it in six months and only performed it four times—in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and in Baltimore at the short-lived but irreplaceable Los Solos performance series curated by Bonnie Jones and Jackie Milad.

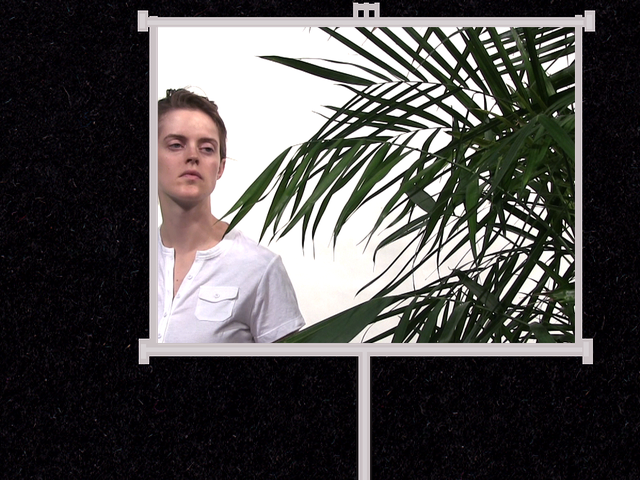

Like a great deal of Barber’s work, Jungle was an exploration of the limits of language’s ability to define reality, delivered in Barber’s heady mix of intellectual seriousness and conceptual playfulness. Now she’s directing a version starring Cricket Arrison and Matmos‘ Martin Schmidt, with sets designed by Peter Redgrave and Heather Romney, the husband and wife creative team behind Smelling Salts Amusements, premiering this week at the Theatre Project.

Two weeks prior to the opening night, Redgrave and Romney’s northeast Baltimore home is being taken over by their set designs, which includes as simplistically elaborate DJ booth made of cardboard. Arrison, Barber, and Redgrave sit around a worktable in the living room, fielding questions about the project. Redgrave notes that Smelling Salts and Barber share a similar aesthetic approach, which they tried to tap into for their designs. In Barber’s works “there’s a sense of play and conceptual ideas layered on top of esthetic ideas,” he says. “So we took some of that and tried to fold in layers of modernist history into the objects that we chose to represent.”

Their DJ booth, though still a work in progress at the time, resembles one of those elevated platforms where globe-trotting nightlife party-starters spin records in Ibizia or some such place, but it also looks a bit like a flowering plant of some sort. “We’re sort of playing with scale,” Redgrave says, “and this shift between the geometric and the organic.”

That’s there’s even a DJ booth with a DJ character is a departure from Barber’s original piece, and part of this “new” version to which she’s still adjusting. In the Jungle follows a scientist (Arrison) who goes into the jungle to research tropical botany. She’s well into her fieldwork when Jungle begins, and she’s typing her field notes and meditating to herself about her activities. She has a radio with her, through which the voice of DJ (Schmidt) keeps her company.

In the original performance that DJ was little more than Barber’s own voice pitch-shifted. “When Martin first read as the DJ I was like, Who is that?,” Barber says. “And now I love it so much. Martin’s an amazingly powerful DJ, sardonic and comforting at the same time. I never didn’t like it. It just felt unfamiliar—it wasn’t as strong a reaction with Cricket [as the scientist] because I never really separated that [character] from me, but with the DJ, I listened to me as the DJ. That voice was in my head.”

That statement is on one level a candid observation and on another a very simple change that opens Jungle up to the exciting ripples that have run through Barber’s recent work. Daredevils, her 2013 film and her feature-length debut, was both an expansion of Barber’s heady linguistic concerns and a profound opening up of her creative practice. It introduced elements of psychological vulnerabilities that always lurked just beneath the surface of her shorts and poetry, but the feature provided a narrative framework for those feelings to bubble nakedly to the surface.

Those qualities appear on every single page of All the People, her recently released short-story collection. Each of its 43 stories fits onto the front (and sometimes back) of a single page, yet they’re all riven with the anticipations, anxieties, hopes, fears, desires, dreams, and failures of extraordinarily ordinary people in an extraordinarily ordinary place. Think of People as Barber’s version of Robert Frank’s The Americans or Larry Clark’s Tulsa: an artist with the compositional eye of a filmmaker documenting quotidian lives with a poet’s succinct verbal fire.

This Jungle continues Barber’s fearless interest in seeing what happens when she allows messy human emotions to enter her creative worlds. When asked why she decided to revisit the piece as a theatrical and film project, she sounds like she suspected this story, and its character, still contained untapped possibilities.

“I never really milked it,” she says. “I just did it a couple of times and sometimes I just don’t want to have orphans lying around. I also thought about Peter and Heather, and I wanted to rope them into doing a project together. And then rope Cricket in so we could become friends. I wanted to approach something in a more collaborative way and give it a chance to blossom where it never had.”

Jungle‘s basic premise hasn’t changed—scientist goes into jungle, then returns to civilization to give a lecture about her work that makes you wonder if she ever actually ventured into the jungle in the first place—but the shift from solo performance to performed piece transforms it.

“One thing I think I’ve been saying to [Arrison and Schmidt] and that I also said to the actors in Daredevils, and I’m a little shy about saying this, but both of [these characters] are just the text,” Barber says, adding that when she said as much she wondered, I probably just want to be a puppet director. “But I’m also interested in becoming more of a director where I could write a character that [an actor could] develop to have a twitch in her right eye. I think that’s really fascinating and maybe I’m just starting in baby steps. So I’ve been saying, Yes, everything you need to know is in the text, but I don’t want to be forcing my hand on it. I’m trying to be as respectful as I can within this limited context and hear what other people have to offer.”

“I think a different person in a role changes things without you having to try,” Arrison says, adding that when Barber first approached her about being in the piece she read it and thought, It’s all about the language and the words. “And I don’t think of myself as that kind of actor at all. I think of myself as a giant, gesture-y kind of guy, so when I think of this piece in terms of making it mine, I haven’t been thinking of it in those [actorly] terms. I’ve been thinking of it more as getting myself out of the way.”

Arrison didn’t see Barber’s 2009 performance, though she has seen a video of it, and she’s quick to point out that she’s not trying to mimic Barber’s approach. They have had many discussions about the text itself, though. “A week ago we sat down and went through it line by line and I asked, ‘Well, what is this about?,'” Arrison says. “Because it’s not a super emotive piece. The goal isn’t for me to act out sadness. Hopefully, if I do my job right, people can form their own emotional conclusions about what’s going on.

“And when we sat down and went through it I feel like at that point I really started creating my own logical sense for what’s happening,” Arrison continues. “Which is in large sense based on what you meant when you wrote it, but also we talked about my own associations for the text and building on that. Nobody is ever going to see that in my performance, but I’m building rich enough layers of that so that it’s real enough for me so it can be real for other people. I am starting to feel like I have more of a center in it.”

This act of becoming is always a fascinating behind-the-scenes peek for any theatrical or cinematic work, but in Barber’s case it is particularly rewarding. One of crushingly human implications Daredevils suggested is that the act of private thought becoming verbal utterance can be as seemingly dangerous as any physical feat of derring-do—as can the act of creation that artists fling themselves into time after time when confronting any blank slate (page, canvas, screen). People echoes that high-wire act in those moments when someone’s internal monologue bleeds into dialogue between two people. With Jungle Barber takes that leap behind the scenes, seeing what happens when a solo piece that lives entirely in one artist’s mind becomes the collaborative creation of a cast and crew.

And it’s refreshing to see that daredevilry welcomed at this stage of the creative process, when the adventurous are getting ready to fling themselves out of the airplane and discover if they properly packed their parachutes. “I don’t yet know what I was looking for” by revisiting it, Barber says. “I wont until I see it done. Right now I’m still getting used to having [these characters] actually be people, thinking about them as becoming their own, and thinking about them within this set.”

She and her crew still have to shoot the scenes for the film version. She and the cast still have to rehearse for this week’s live production. She will still have to edit footage into the film she’ll release later this year or early next year. She doesn’t really know what these two new versions of the project are going to be.

But she’s going to find out. In the Jungle “hasn’t changed yet,” Barber continues. “It’s just this,” she says, holding her out her clenched hands. “But I’ll get there.”

In the Jungle runs Aug. 14 and 15 at the Theatre Project. Please note that there will be two instances of video documentation during the performance in which the audience may be seen, and audience members will be asked to sign an appearance waiver.