Joseph Shaikewitz’s Top Ten List of the Most Impactful Online Art Writing of 2015

Art criticism has been placed under a microscope in 2015: the Walker organized the three-day panel “Superscript: Arts Journalism and Criticism in a Digital Age;” ARTS.BLACK celebrated a full year of foregrounding Black voices in art criticism; and the institution of art writing took center stage in “Bound 2”—an annual publication executed by interns at The Contemporary (in this instance Lily Clark, Jazmin Smith, and myself).

For all that this extensive, growing, and above all necessary scrutiny of criticism has achieved, it remains the task of the writer to not only be versed in this discourse and grapple with its particularities, but at the end of the day to produce meaningful pieces of cultural writing.

What follows is a subjective attempt to highlight exemplary texts, essays, and reviews that have emerged through this polemical upheaval of the status quo. While any ‘top ten list’ is inherently limited and limiting, the pieces included constitute those that have stuck with me, affected my day-to-day musings, and re-structured how I see my own practice as a writer, curator, and advocate for the arts. With both candor and emotional accessibility, oftentimes through the lens of an overlying and socially motivated question, these works of writing effectively ground a practice that has fostered (and oftentimes maintains) a reputation as detached and aloof.

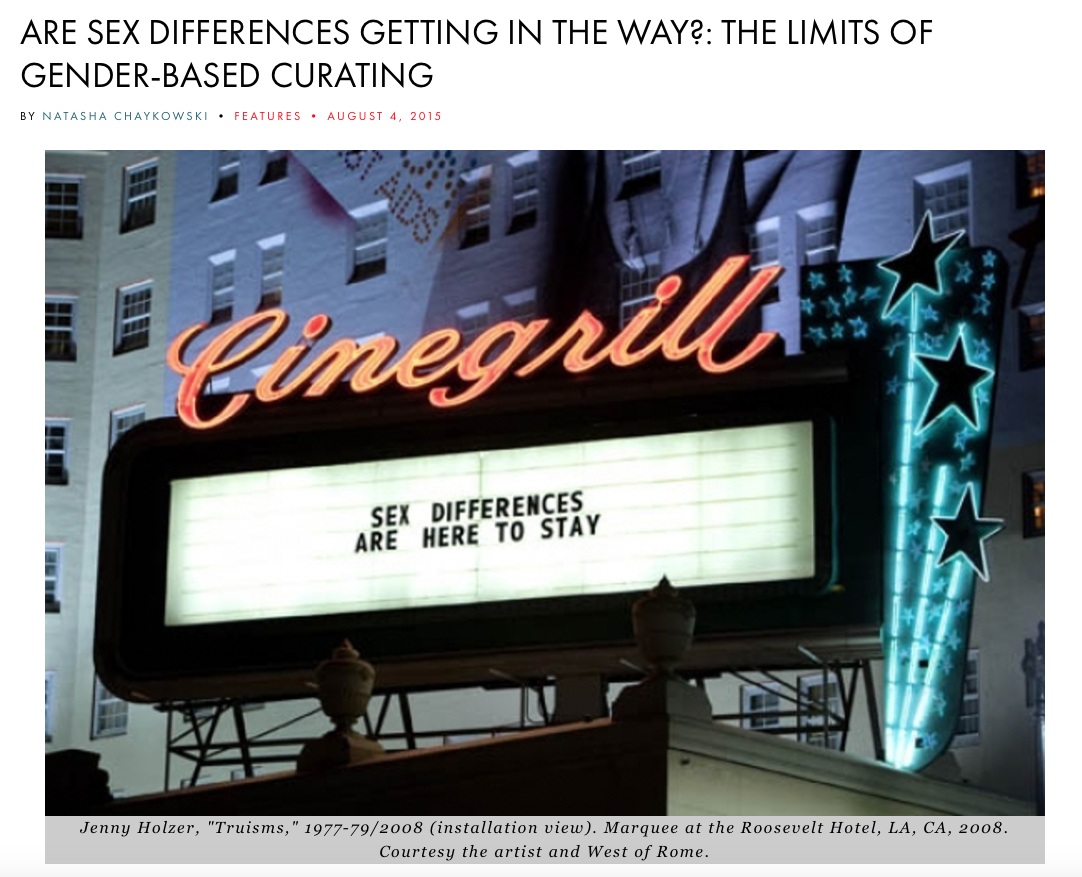

Chaykowski’s review of QUEENSIZE at the me Collectors Room in Berlin is one that I’ve returned to on multiple occasions. Her ability to consider an exhibition of all female artists within a broader context of the historical impetus but latent shortcomings of gender-specific curatorial approaches delivers a complex piece of criticism that advocates for more nuanced specificity in the treatment, classification, and reception of work by female-identifying artists.

“Such women-only institutions and exhibitions promote a critical method of seeking parity in the face of deep-rooted privilege structures. And thanks to the earnest and unflagging labor of the feminists who spearheaded such projects in the 1970s, my generation has enjoyed opportunities and benefits hitherto out of reach. However, exhibitions centered on radical or separated communities bear their own set of strictures. They can propagate particular sets of exclusionary criteria, while also limiting potential readings of the works.”

Maura Reilly, “Taking the Measures of Sexism: Facts, Figures, and Fixes,” ARTnews.

Deploying hard facts and statistics, Reilly blows the whistle on the pervasion of sexism in the art world, concretizing a sentiment that is undoubtedly felt and experienced but oftentimes lacks the data that can force even the most pigheaded of skeptics to face the truth. Her essay functions as a modern day addendum to Linda Nochlin’s seminal “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” and illustrates the current condition of gender representation across numerous pockets of artistic activity.

“Linda Nochlin urges women to ‘be fearless, speak up, work together, and consistently make trouble.’ Let’s not just talk about feminism—let’s live it. Don’t wait for change to come—be proactive. Let’s call out institutions, critics, curators, collectors, and gallerists for sexist practices.”

Adequately valuing one’s own work is tricky to begin with given the strong classist divisions in the art world, but that problem is especially amplified when it comes to performance art. Ghoarshi surveys the financial pitfalls that underlie the burgeoning medium and considers how strong institutional support and incorporation of performance along with steadfast demands from artists help to prioritize this conversation.

“High-profile exhibitions such as the Whitney Biennial and the New Museum Triennial are placing performance front and center in their programming. Museums are acquiring performances for their permanent collections and hiring curators devoted to the tricky task of preserving them […] Yet, at the same time, artists and organizations are raising questions about how performers should be paid for their labor.”

Raphael Rubinstein, “Total Service Artists,” Art in America.

Rubinstein considers many of today’s artists’ espousal of (or oftentimes expectation to) become all-in-one agents of artistic production, historicization, promotion—you name it, really. Through a number of case studies, this essay offers an astute overview of how this rise in the responsibilities that fall on an artist’s shoulders can dubiously shuttle between increased autonomy and the assumption of more risk and precarity.

“Do-it-yourself tendencies shouldn’t surprise us, since from its beginnings modern art has involved the pursuit of autonomy (from tradition, from society, from patronage, from limiting styles), a refusal to cede control to anyone other than the artist. Further, by taking on such everyday, seemingly ‘noncreative’ activities, artists have contributed to another quintessentially modernist project, the demystification of art.”

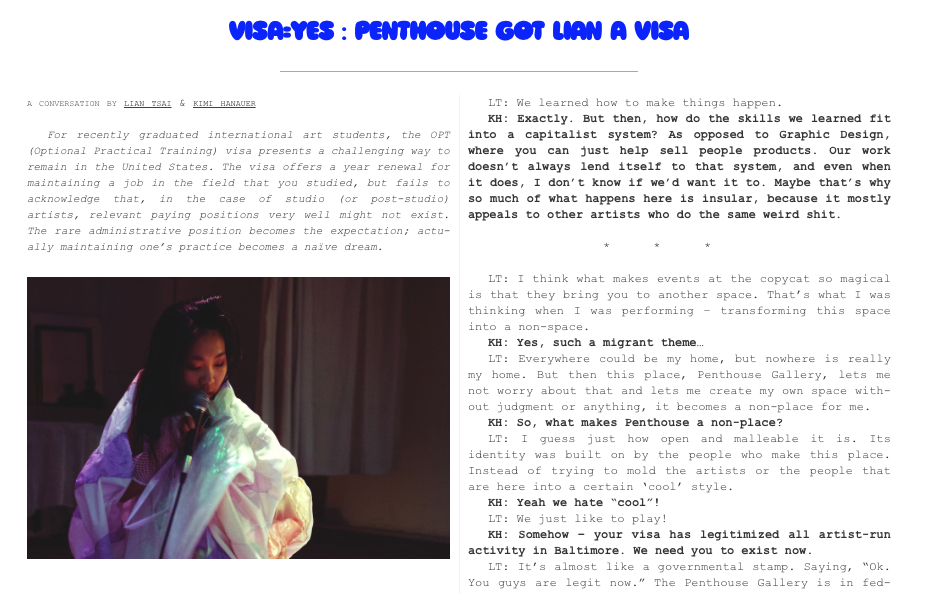

Lian Tsai and Kimi Hanauer, “Visa=Yes: Penthouse Got Lian a Visa,” Post-Office Arts Journal.

Lian Tsai and Kimi Hanauer, “Visa=Yes: Penthouse Got Lian a Visa,” Post-Office Arts Journal.

Lian Tsai and Kimi Hanauer of Penthouse Gallery, in a conversation centered around the former artist’s immigration trials and tribulations, touch on topics including the realities of sustaining an art practice; the legitimization of artist-run initiatives; nationalism and identity; and the real contributions that artists make to cultural, social, community-based circles. I love this read as well as Tsai and Hanauer’s ability to open up about just how complex and nuanced the abovementioned issues prove to be in their own daily experiences.

“The fact that even though [the act of running Penthouse Gallery] is not visible or accessible in a lot of ways, can get someone a visa, a completely life-changing thing, the fact that you can stay in the United States for another year because of this bullshit we do—it kind of legitimizes what happens here while also playing the system. We were able to use this system, that otherwise seems very oppressive, in order to legitimize work that also exists outside of dominant institutional platforms.”

Michael Anthony Farley, “What’s the Use of an Art Critic in a City on Fire?,” Art F City.

Michael Anthony Farley, “What’s the Use of an Art Critic in a City on Fire?,” Art F City.

In the wake of the death of Freddie Gray in the hands of six Baltimore police officers (and in solemn continuation of the decades and decades of systemically-enforced inequalities that have contaminated this country), a sense of sheer exhaustion could be felt across the city. Michael Farley proves that, even among artistic communities, we can and should be talking about these issues and, in a sincere and modest essay, unveils the privilege of practicing as an art critic.

“Truthfully, I’ve wanted to cry for black Baltimore, but I don’t feel like I’m entitled to those tears. And deep down, I know that many people agree with me. I think I haven’t been able to get words in writing because I’ve been unsure of the validity of my feelings over the past few days. Hell, I’m unsure of the validity of any of the facts I’ve heard in the past few days. It’s been an emotional roller coaster.”

Orit Gat, “What is an Art Critic Doing at an Art Fair?,” MOMUS.

Orit Gat, “What is an Art Critic Doing at an Art Fair?,” MOMUS.

Orit Gat’s writing consistently hits the mark and so her artful take on the overlap between criticism and art fair culture comes as no surprise. Here, she legitimatizes not only the position of the critic to approach art fairs as possible subject matter but also the need for criticism to tackle and address its own relationship with the art market. This notion of no-holds-barred criticism can be applied to similar corners of the art world and at the same time advocates for a forthright approach to writing art criticism.

“Artists, curators, critics, and dealers need to delineate – possibly constantly redraw – their respective relationships to the art market. We need to test the ethical waters with every step we take into the deep end of this economic system. Does participating at a fair’s talks program or curating a section of a fair make one complicit in any kind of way with this translation of cultural capital into dollars? Critics can’t afford to pretend the market does not exist. A critic’s role is to shape the conversation around it.”

Andrew Berardini, “How to Art Fair,” MOMUS.

Andrew Berardini, “How to Art Fair,” MOMUS.

This year I was fortunate enough to spend the first week of December treading through the noise of Art Basel Miami Beach. Upon returning with both high and low first impressions (as expected), I found solace in this piece from Andrew Berardini. He quickly gets down to the essence of art fairs and the nonsensical para-reality that they devise for a handful of days out of the year. Beradini makes sense of the exhaustion and disillusionment that I felt through a piece of writing that reads as satire but is eerily rooted in the truth with few exaggerations.

“Every person you run into you exchange a standard set of information: when did you arrive? when are you leaving? what have you seen? what are you doing later? For those with an iota more attention, you might get a ‘what have you been up to?’ No one has to answer this question; you’re at an art fair. […] This depresses the hell out of you, so you talk about hikes you’ve taken instead.”

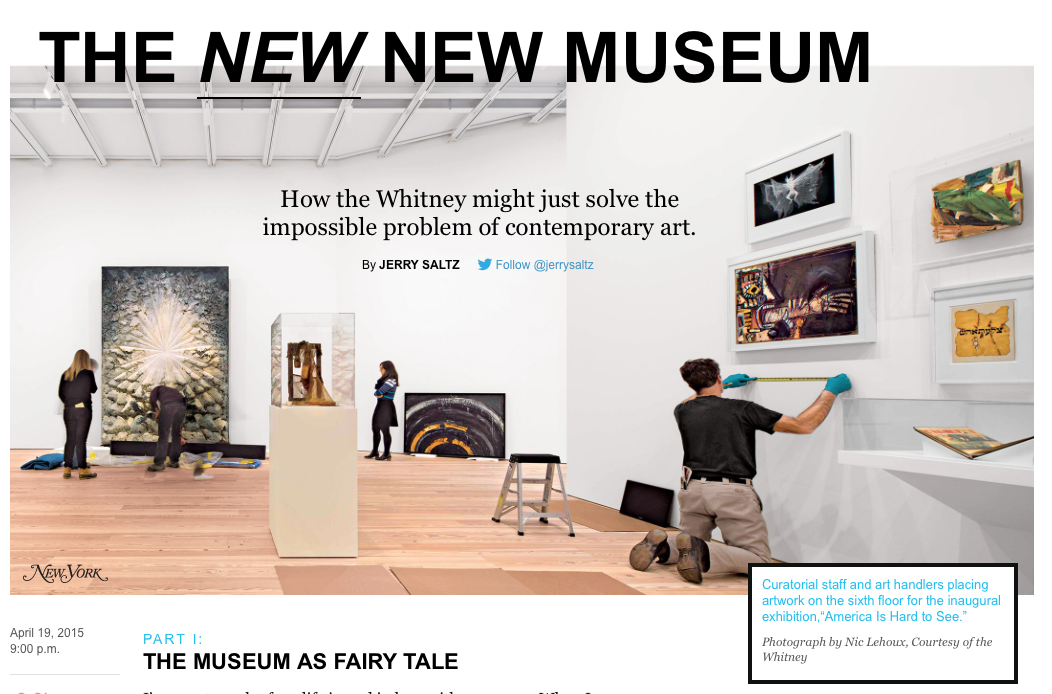

Jerry Saltz, “The New New Museum,” Vulture.

Jerry Saltz, “The New New Museum,” Vulture.

On the occasion of the Whitney Museum’s re-opening in the Meatpacking District, Saltz published a landmark review of the state of museums in New York, skillfully traversing questions of spectacle, cultural competition, insularity, and why it is that we need museums through a stirring historical purview. Saltz truly hits the nail on the head and spells out how the new Whitney and its many successes might signal a new standard for how museums conduct and construct themselves.

“So I knew early on that museums were not fairy-tale places — that the practice of enclosing and curating a history of art within marble walls enclosed prejudice and even bloodlust, too. But I also knew that those buildings enclosed touchstones, benchmarks, cultural skeleton keys, divinations, extraordinary probings of the human imagination […] I knew, in fact, that they contained something ecstatic and represented something eternal.”

From one ‘top ten’ list to another, I have to bow down to Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham’s summary of all that ruled in 2015. They address the progress made (and that which remains in dire need to come) across issues of representation, inclusion, and co-opting real and digital spaces as one’s own. Two powerful minds who have recently teamed up under the moniker Black Futures, Drew and Wortham exemplify two reasons among many that the year to come is sure to wow us.

“Global interconnectivity was turnt in 2015 and we can’t wait to see what 2016 has in store.”

Author Joseph Shaikewitz is a Baltimore-based writer and curator from St. Louis, MO. He is the Gallery Manager at Hamiltonian Gallery in DC and a graduate of Johns Hopkins University.

Featured Image: Jenny Holzer, “Truisms,” 1977-79/2008 (installation view). Marquee at the Roosevelt Hotel, LA, CA, 2008.