A Conversation with the authors of “Scroll 3: On Site” by Joseph Shaikewitz

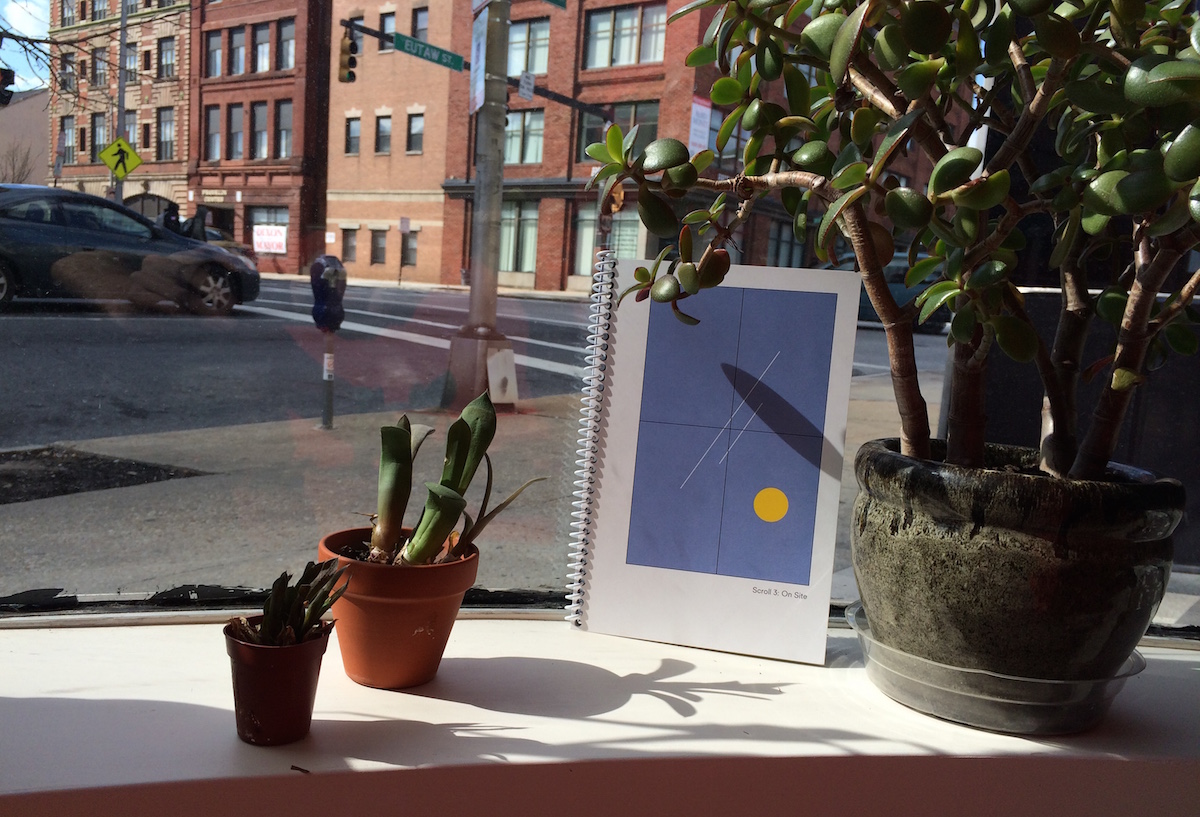

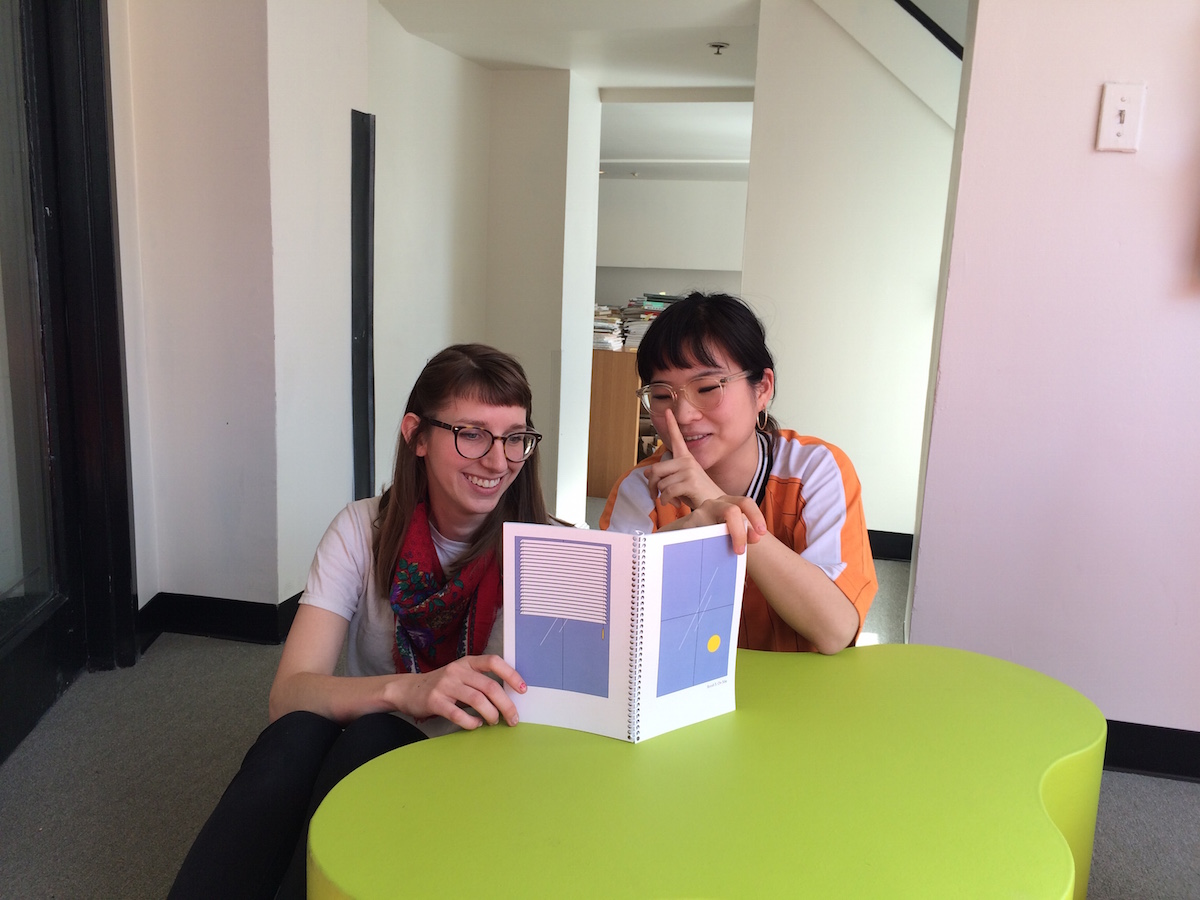

“Scroll 3: On Site” is a forthcoming publication by Brandon Buckson, May Kim, and Allie Linn—current interns at The Contemporary—which will debut this April at PMF VII. The third Scroll in the series, “On Site” continues the legacy of this annual, intern-produced project and takes the dynamic and fluid identities of many of Baltimore’s brick-and-mortar locations as its point of departure.

The result is a thorough, critical, and above all enlightening publication that reveals the vital histories of so many of this city’s beloved arts spaces, oftentimes for the first time in the lifespan of these projects. In reading this volume, familiar and unfamiliar sites appear more and more as architectural iterations in a long series of palimpsests—pages of a scroll or book that are partially erased and later overwritten ad infinitum—as the impact of Baltimore’s past seeps into our understandings and manifestations of the present.

Scroll was initiated in 2013 with Max Anderson, Kimi Hanauer, and Lee Heinemann proposing and subsequently producing an entirely intern-led publication; their inaugural Scroll, titled “I Don’t Care, I Love It,” questioned the interconnectivity of the local art scene and was released the following year.

I was apart of the succeeding cohort of interns along with Lily Clark and Jazmin Smith, where we were given the opportunity to release “Bound 2”—a reflection on the impact of art writing, criticism, and publishing on the creative scene at large. Knowing firsthand the rewarding, albeit trying nature of assembling such a publication, I was thrilled to sit down with two of the minds behind “Scroll 3: On Site” to discuss the act of archiving, the ethos of citywide turnover, and the importance of the individual. To start, could you explain the idea behind the title “On Site”—which follows in the tradition of lyric-inspired Scroll titles—as well as the conceptual impetus behind this publication?

To start, could you explain the idea behind the title “On Site”—which follows in the tradition of lyric-inspired Scroll titles—as well as the conceptual impetus behind this publication?

Allie Linn: Working on the third edition of Scroll put us in a really unique position: there’s a kind of structure that has been created, but there’s also so much room to still explore what Scroll can encompass. So much of this publication is about exploring histories of spaces and backtracking to learn about different projects that occupied singular spaces, so we were interested in the title doing that as well. I personally really liked how the second Scroll [“Bound 2”] looked to the first [“I Don’t Care, I Love It”] and borrowed that idea of using a song lyric as a title. It felt like something that had been given to us to uphold.

May Kim: It just kind of came to us, but we definitely wanted it to be historical in an architectural way. We went through a number of different titles and then we were like “you know ‘On Sight’ by Kanye?” Like site-specific, so “On Site.”

That notion of the site-specific definitely comes through as well as this riff on the idea of Robert Smithson’s ‘non-site;’ is that something that’s reflected here?

AL: I’d say only in the sense that in the beginning we were questioning what constituted a space—that’s a question that’s come up and changed a lot. Whether we were looking at buildings that housed projects or nomadic projects that moved to different spaces, there are a lot of kinds of arts projects that exist in Baltimore. Some of them are very much tied to a space and some of them are much more about the collective of people involved without being tied to any space at all. We looked at a lot of different projects that did both of those things and in the end, this specific publication focuses on individual addresses and different projects that have occupied them.

This provides an interesting antithesis to The Contemporary, whose mission and identity revolves around a nomadic impulse—going into different sites to mount its projects.

AL: It is kind of the other side of the spectrum.

Exactly. I’m curious if that relationship in any way spurred the topic that you’ve chosen. Or even if the upcoming project with Abigail DeVille informed your route at all.

MK: I think it definitely did. We do a lot of research outside of Scroll that’s about Baltimore’s history and I go on site visits with [Program Manager] Ginevra Shay and look at potential locations for future projects that I didn’t even know existed. Like Martick’s, the bar that’s next to Platform Gallery that I had only seen in passing. I got to go inside and there’s a bar that’s still there from decades ago. And the Marble Bar that’s in the basement of the Congress Building that used to be a punk show venue. We think of these site visits as a separate project, but I think it influenced what decisions we made.

AL: There is definitely a lot of overlap with the project that Abigail is working on now. Her exhibition [“Only When It’s Dark Enough Can You See The Stars”] at the former Peale Museum is really similar to what we’re doing with Scroll: taking a singular piece of architecture, diving into different archives, and talking to different people that have relationships with a single brick-and-mortar location. We really had no idea about Abigail’s project going into Scroll back in August, but it was pretty serendipitous that the two overlapped.

MK: I’m looking back into our first brainstorming meeting and I think we were influenced a lot by the Baltimore Uprising and the voices of Baltimore’s youth and minorities. We all had a mutual interest in the city’s artist-run spaces and artist-run non-art spaces. The questions that we started with were really: Who should be reading this? What audience do we want to reach? Do we want to reach those already invested in The Contemporary in some way or a broader audience who may be more unfamiliar with the related art sphere?

AL: It’s such a huge idea to make a publication about the arts landscape of any place, but especially Baltimore. I find that it’s a very thoughtful, articulate, interesting, and involved community of people here who are really tapped into what’s going on politically and socially. It’s a very responsible city—I feel like people are very sensitive to what the arts community is here. I was actually just talking to [artist] Max Guy about this because it’s interesting how every couple of years it seems that some kind of article or publication comes out that does try to understand what Baltimore’s art community is right now.

When we were first brainstorming this huge, nebulous idea of Baltimore’s art community, one of the things that stuck out in my mind was my own relationship to it, which is primarily through Bb—the gallery that I run with my partner [Colin Alexander]. Something that I’ve always really liked about that space is that we moved into it knowing that it was a tailor shop. In the basement there are still enormous boxes of spools of thread and rolls of felt and there are pins stuck into the carpet. It’s this very nice and tangible reminder that this was a business at one point. Its history is just as important as what’s going into it now, so that was kind of a lead-in for me.

MK: Right, it was sort of a spark: “So what about Load of Fun, etc.?” There are all these spaces that we’ve seen on a daily basis, but we don’t know what came before them.

AL: It made us begin to question all the spaces that we’re familiar with as ‘arts spaces.’ For the most part they weren’t built for those purposes and that brings up a lot of big questions: Who owns them? Who’s renting them? Who has the opportunity to rent them? We’re renting Bb now with five other artists, but when do you get priced out of a neighborhood? It opens up a lot of questions and made us at least interested in finding out more about a lot of these spaces.

I find there’s something really beautiful in making visible things that have become invisible over time, as this publication does. You referenced that this project came in the wake of the Baltimore Uprising where we saw communities making themselves and their needs visible at a time when there was such an influx of media and national coverage. I wonder if there’s an overlap between what was circulating around Baltimore at that time and your aim to seek out unseen histories.

MK: I remember in the beginning, we were very influenced by the Uprising and we wanted to make a publication on that topic, but ultimately decided to think more broadly so that it wouldn’t be too tied to a specific time. There were so many writings and works about the Uprising that were being made at that time, so we started looking into things that we could write and do research about that could last longer and for people to look back to in the future. I think that’s why we started talking to more people about their opinions; we both agree that these conversations were the best part about doing this research.

AL: I think that visibility is important too in that this was an opportunity to find out the histories of these spaces that ordinarily aren’t really on anyone’s mind or don’t really have the opportunity to be remembered. I think that’s also a generational thing. I remember in the beginning we were having a lot of conversations about how the art scene here is very much rooted in an art school—which I think is pretty true of most major cities—but this means that a lot of people move to Baltimore and live here for four years and then move away or only stay for a year or two. It’s a pretty narrow way of seeing a city. You come and you leave and your understanding is those four years.

It also means that when projects do arise, people tend to think, “This is super innovative, this has never happened here before!” In reality, that’s almost never true in an arts context or in any context. We were interested in that idea of looking back and specifically seeking out multiple generations in order to hear from many different voices and find out what was happening twenty, thirty, forty years ago.

Could you speak to your working methodologies for finding these spaces? I mean today, you can go into a place like Turp’s and have no idea that it housed Proposal Gallery in 1979—it’s basically a ghost within the memory of the space.

AL: We’ve made lists of so many places, but some of it came down to logistics. Unfortunately, it’s very telling which places you can find information about. There are spaces where we were able to find more information on than others, so that became part of the curatorial process.

MK: It was mostly through the conversations we had. The first interview we had was with Craig Hankin who was the founder of City Paper and he is a living encyclopedia of Baltimore history. He was giving us all these names that we’d never heard of and that was a shock for us because we thought that we had a good idea of the Baltimore art scene. For me, I’m an outsider—I didn’t grow up in Baltimore—so I thought this city’s DIY gallery scene was so innovative, but some people were doing similar work in the 70s.

It all came up in the interviews with Craig as well as Alex Martick, who was the owner of the Martick’s bar. He’s 82 years old and I was asking him, “have you been to the galleries around [the Bromo Arts District] like Current Space?” and he was like, “I don’t know what any of these things are that you are talking about.” And I’d ask him, “What would you do for fun when you were younger?” and he was like, “I would drink and hang out at Martick’s with some friends.” There’s just so much that we don’t know.

Martik’s bar now

Martik’s bar now

AL: Some of the buildings were ones that we were familiar with, but maybe didn’t know too much about beyond walking by them. The way we stumbled upon the Downtown Gallery was a fluke. The Baltimore Museum of Art had just installed its show of late-20th century photographs from Russia and Belarus and the wall text mentioned that those works had been bequeathed to the Museum by Brenda Edelson. It very casually mentioned that she was the “former Director of the Downtown Gallery—the country’s first satellite gallery.” I’ve worked at the BMA for over a year at this point and I’ve lived in Baltimore for almost fourteen years and I had never heard about that project.

I was able to spend a lot of time in the museum’s archives and library working with the librarian Emily Rafferty. Brenda lives in New Mexico currently, but we spoke when she visited the museum a few months ago and had a few follow-up conversations. It was really incredible to sit down and hear about that project and the exhibitions they put on inside.

There are so many conversations today about making art spaces more accessible to the public and the Downtown Gallery was such an obvious answer to me—to have a place in the middle of the Downtown neighborhood where people are at work at the office. Just putting out food during open hours—which would coincide with the offices’ lunch breaks—would attract this enormous crowd of people who would probably never go to a gallery otherwise.

MK: And they had amazing exhibitions there.

Allie, in your essay “On History, Naming, and Archiving”—which is very smartly written—you talk about how archives present themselves as objective, but are very much informed by larger social biases and hierarchies. Were these conversations that you had a way of filling in any gaps in archival knowledge that you may have encountered?

AL: I think we were really drawn towards conducting these interviews precisely for that reason: hearing these oral histories firsthand from people that were there, unmediated by written history. But the same problem can arise when you try to find someone to speak to a certain space.

One of the projects that we were looking at for a long time was the Royal Theatre, which is arguably the most important jazz theater that has ever existed in Baltimore. That’s a building that’s been totally razed and the only thing that exists is a small brick monument that names it as the previous site of the Royal Theatre. I spent so much time trying to find someone who could speak firsthand to attending the Royal Theatre as a child. Mostly that’s the date gap; the Royal was opened almost a century ago, and many of its original patrons are no longer around to recall its history. It also goes back to the idea of which projects have been recorded and documented extensively versus which ones have been forgotten or left behind historically.

It seems as though you all set out to be very objective in how you selected which sites to highlight. Was there a deliberate effort to remedy these lapses in archival material?

MK: I think about halfway through our project we came to realize that a lot of the spaces we were researching were white-owned. So we definitely looked into more diverse projects. I realized myself that all the art spaces that I go to are in the comfort zone of my neighborhood. We started reaching out to places outside of Bolton Hill and Seton Hill and had probably some of the best conversations.

AL: At one point we mapped out all of the spaces we were looking at and definitely the designated ‘arts districts’ of the city are where projects are happening most frequently, or at least being written about and advertised most. I think that also speaks to a lot of bigger issues. We were deliberately trying to find spaces in farther East Baltimore and farther West Baltimore to fill in these gaps. But this is the tragedy of poorly distributed resources in Baltimore. There are so many neighborhoods that still lack basic access to healthcare, public transportation, and grocery stores. So how could you possibly expect for there to be a thriving arts community? And there are definitely a few—Jubilee Arts, Six Point Pictures—but it is another reminder of where city planning has failed its residents.

MK: Brandon [Buckson] writes about this in his essay “Site Specifics”—the lack of governmental care in these communities. He brings up a really important point that Baltimore right now is in the limelight for black youth; after the Uprising, a lot of national attention was on the city. Brandon talks about how there could be a pressure to be in that spotlight, but also have to struggle to create art and you become the ambassador to represent your culture. I think that’s something that we were trying to keep in mind as well in our research process.

AL: In the end, I think the important thing that we kept reiterating is that these are ‘case studies,’ so they’re a very small sampling. There are eight case studies that made it into the publication and those were switched in, edited out, moved around. There are so many more projects going on, of course. We say in the publications that nothing is totally complete, it’s more dipping your toe into understanding. There are so many different points of views for these spaces. People have very strong opinions about a lot of the projects that these spaces housed. I think it’s really good that they do because it shows that there’s a lot of investment in these projects that we mention in this publication. But it so easily can turn into a very polarized perspective, deciding what is a right ethical decision and deciding what’s not.

That’s something that I struggled with myself in reading this. In some instances, projects are forced out of buildings by rising real estate costs or the projects themselves come to an organic end. In these conversations, did you notice people looking back with positive memories, more skepticism, or is it far more complex than that?

AL: It’s definitely complex. But I will say that with everyone we talked to, they were all very positive conversations. I think this was supposed to be a celebration of many different kinds of arts projects that have existed and so even in the cases where projects may have closed prematurely, everyone we interviewed is still very much active in the city.

I like that idea of an archive as a “celebration.” Even if there are flaws and quirks that come to the surface through this information, that’s what constitutes the particularities of a city. I think that “On Site” really does that—giving people the chance to look back at what their projects accomplished and accomplish.

AL: And fast turnaround isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s a conversation I’ve had with a lot of artists in Baltimore because many projects are made to have a short duration here. People will start a project space with the intention of it only lasting a year or two and I think there’s a misunderstanding that this is viewed as a failure or that you couldn’t pay the rent or that this wasn’t financially sustaining; most of the time, those projects aren’t meant to be financially sustaining. It’s as long as it needed to be. It had a specific duration. I think that’s also the beauty of a lot of the spaces, at least in this area. They’re constantly changing and are able to have a new voice frequently enough that it doesn’t get static or dull.

MK: I agree that it’s what keeps Baltimore’s art scene exciting. I am also really glad that people are willing to take that on themselves. I find it really cool that people are willing to team up together and make collectives. It’s so easy to be a participant, but a lot of people are willing to say, “we could do this.” That’s what we were hoping to do, too—encourage people to do this themselves. You just have to start it and people will come to you.

Are there any design choices that you made to reflect the content and subject matter?

MK: It changed a lot. At first we were going to have eight covers for our book so there was never a beginning or a table of contents, but we found out that would be really expensive. So it still has chapter covers, but we didn’t really want a linear book design.

AL: I think the form came before any of the content.

MK: We were like “spiral bound! Eight covers! All these case studies! No beginning, no end!”

AL: We wanted to eliminate any sense of a hierarchy so we were drawn towards spiral bound because it’s almost infinite; there’s no starting point, it doesn’t have to follow a specific narrative. You can pick it up from any point.

MK: Which it still does. You can start anywhere and stop anywhere.

AL: It’s kind of that Deleuzian thing: all of these are feeding off of each other in the same way that some of the newer spaces are looking towards the older spaces and vice versa.

Since you’re both very involved in the Baltimore arts landscape, I’m curious if working on this project has made either of you reevaluate your relationship to this city or the cultural scene?

AL: I feel that everything can only help you grow as an artists, curator, writer, or participant in this city’s art scene. Certainly the research and the conversations and the dialogue that went into producing this Scroll put me in contact with a lot of new people that I never talked to or whose projects I wasn’t aware of. So in the most basic sense, I feel much more well-versed in previous and current projects. It’s also always really invigorating to see what else is going on right now in Baltimore. It’s so good to see projects like Balti Gurls and Kahlon finally getting recognized in major media outlets for things that they’ve been doing for a really long time.

MK: I agree with you. Something that I was excited by came up during the roundtable with the EMP Collective where [collective member] Carly Bales said that sometimes it’s just a matter of showing up to these spaces. So even if you’re not an artist, you don’t have to have a show or curate something. Participation is as important as making. That’s something that I learned: sometimes you just have to show up. Now anytime I get an invitation to something I’m like “I have to go now!

What would you say that you’re most excited about in sharing your edition of Scroll with the public?

MK: Something I’ve been really interested in as a ‘millennial’ is how history is so blatantly biased. “Who gets to write history?” is a conversation we have a lot and so participating in writing history is really exciting. That could be anything; it could start small and as long as you keep doing it, it can encourage other people to keep collective memory and write history together. I think it will eventually grow into something bigger.

AL: I’m really excited to share all of the stories and conversations we had and provide some access to projects that the city has housed. Creating Scroll was such a special process because we got to speak one-on-one with so many people in Baltimore who have done such incredible projects.

MK: We probably wouldn’t have had the opportunity to talk to them if it wasn’t for this publication.

Author Joseph Shaikewitz is a Baltimore-based writer and curator from St. Louis, MO. He is the Gallery Manager at Hamiltonian Gallery in DC and a graduate of Johns Hopkins University.