Macon Reed Explores the Roots of Misogyny in DayGlo Color by Cara Ober

The Old Testament book of Exodus (22:18) states, “Thou shalt not permit a sorceress to live.” I’m not sure how many of you are in the same boat, but I suspect that if I were living in 17th Century America, I would have a good chance of being accused witchcraft; not because I’m actually a witch but because I am a loud and secular non-conformist. You probably would, too.

Although scholars argue over the causes and statistics, in Europe between the 14th and 17th century, 40,000 to 200,000 people were killed for practicing witchcraft. This makes America’s witch-hunts seem paltry in comparison, with approximately 80 people accused and three dozen people executed in the colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Haven in the 17th century.

Some historians believe the Church fraudulently invented witches in order to centralize authority, impose cultural conformity, crush opponents, and encourage repopulation after the Bubonic Plague. Others believe the Church wanted to eradicate the last vestiges of the paganism long practiced in Europe before Medieval times.

Common methods of execution for convicted witches were hanging, drowning, and burning. Burning was favored in Europe, because it was a more painful way to die, while the American colonies generally preferred hanging.

Various acts of torture were used against accused witches to coerce confessions and name their co-conspirators. The torture of witches began to increase in frequency after 1468 when the Pope declared witchcraft to be “crimen exceptum,” removing all legal limits on the application of torture in cases where evidence was difficult to find. Sometimes those who endured torture without confessing were released, but in most cases torture added to a broadening social panic because it induced false confessions and identifications of many others as being witches.

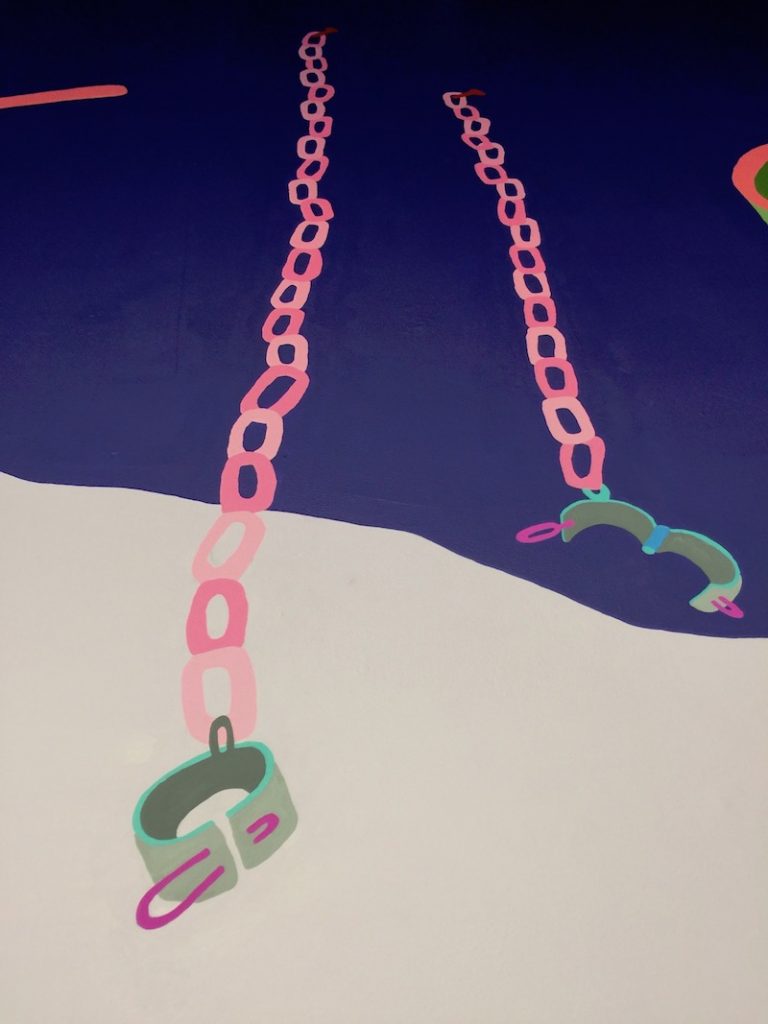

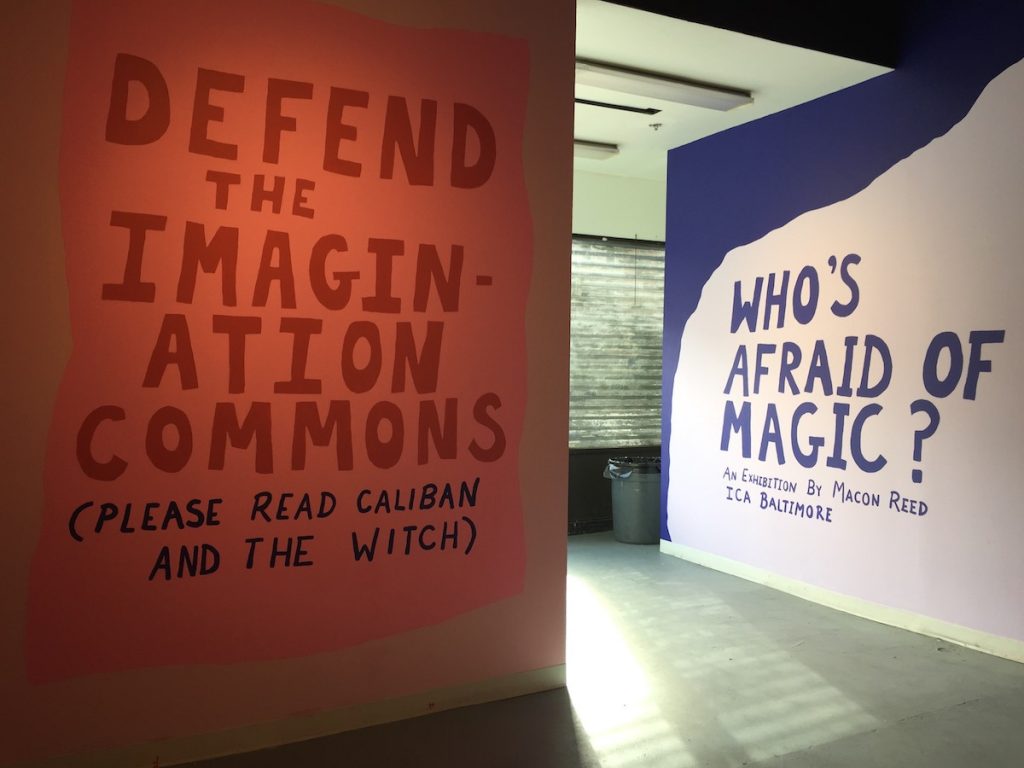

I didn’t know any of this when I first visited Macon Reed‘s solo exhibit titled Who’s Afraid of Magic? The first thing I noticed was this show, produced by ICA Baltimore and hosted at Spacecamp, fills the cavernous space in an ambitious, convincing way. The artist’s use of cute cartoon shapes and Day-Glo candy color makes the exhibit feel, at first glance, cheery in a Yo Gabba Gabba way. Then you notice the gallows. And the handcuffs. And the weird pincher tongs. And the stylized dresses clustered in the middle of a circle of fire.

The artist makes more information available in a printed statement which includes text from Caliban and the Witch (2004) by Silvia Federici, which examines the changing role of women from feudalism to capitalism, especially their role as exploited “producers” of offspring, which inspired this exhibit. As opposed to a supplementary text, it feels like an essential part of the exhibit.

Here are a few of the statements Reed has pulled from the text that are relevant to understanding this work:

The Bubonic Plague killed approx 36-60% of the population in Europe between 1346-1353. It become more important for women to reproduce in order to regenerate the masses. All sexual practices that did not facilitate reproduction were deemed sins: abortion, contraception, certain practices, being gay. Women’s roles and the feminine were shifted towards submission and valued primarily for reproduction of the labor force.

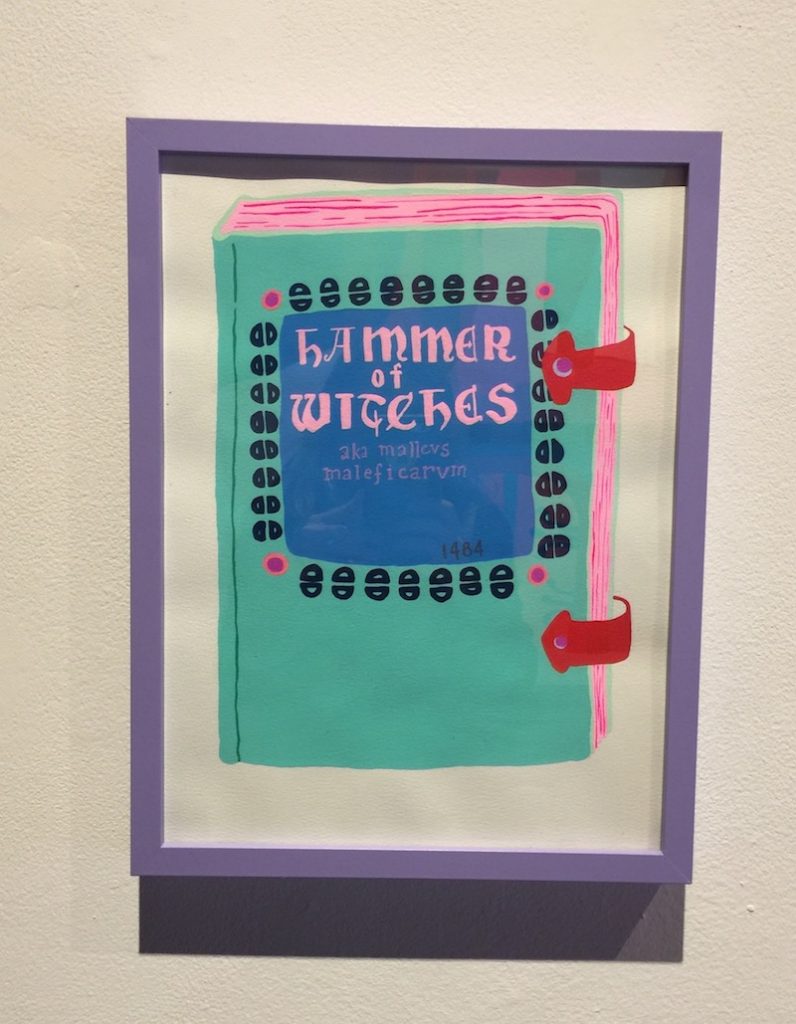

The Malleus Maleficarum translates to the “Hammer of Witches” was once published second most in Europe only to the Bible. The book elaborates in gruesome detail how to find, catch, torture, force confessions from, and execute women deemed to be “witches.” Originally published in 1484.

The Breast Ripper was an iron medieval torture device that was heated up and used on the bodes of women, primarily those accused of adultery or self-performed abortion.

“Scold’s Bridles” were used primary on lower class women to punish them for “riotous” or “troublesome” speech and/or witchcraft. They inflicted pain an prevented speech.

Public hanging of women accused of witchcraft were common practice to instill fear among the public, with bodies left outside for days.

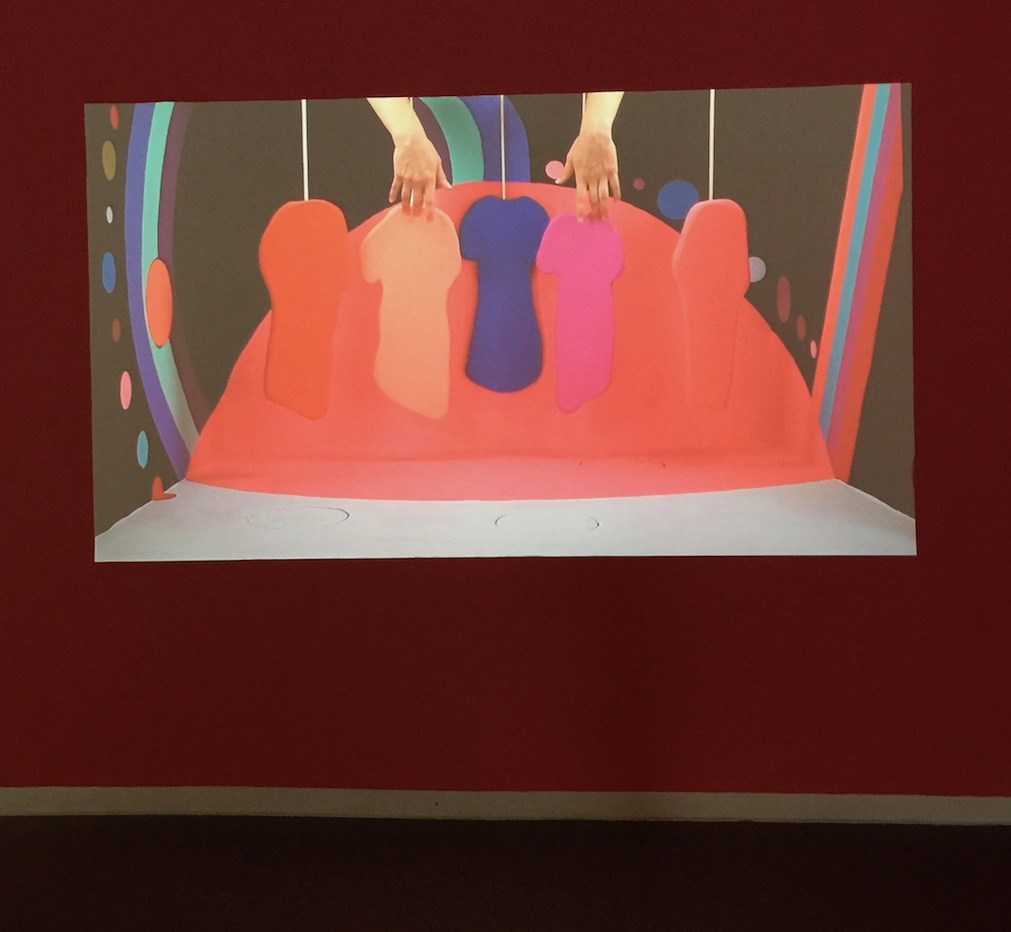

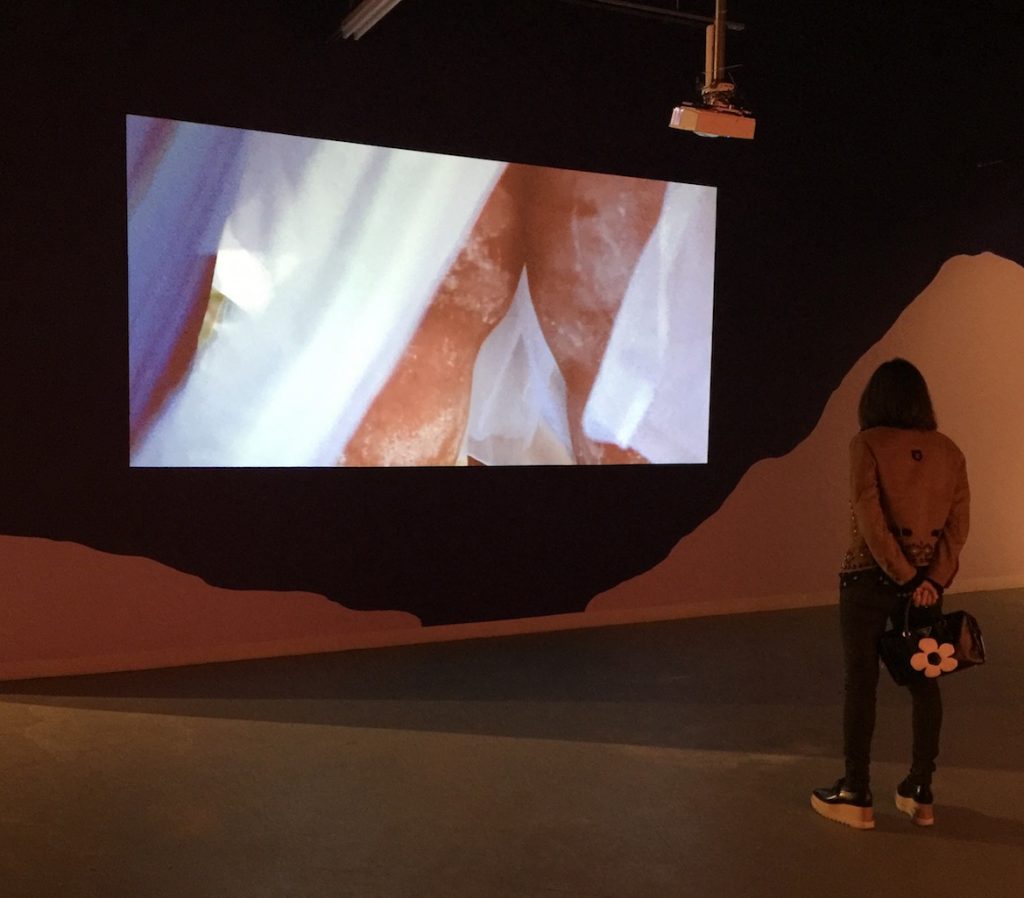

As you venture deeper into the cavelike gallery, painted from floor to ceiling in a loose sequence, your mind begins to integrate the visuals and the text. The space and the narrative grows darker at the same time. Unlike past exhibits at Spacecamp, Reed has harnessed the scale of the dramatic environment through activation of its walls with large-scale murals and projected video. Hues of deep red, purple, and white build a fantasy landscape around you that is solid and cohesive, and video screens are seamlessly integrated.

In this oversized-space, Reed’s videos read as cinematic, monumental, and lush. Although the artist’s statement equated historic witch-hunts with modern day consumerism and fascism, this connection wasn’t explicit in the video and this is a good thing. Keeping the narrative open allows the viewer to equate loss of agency with imagination, whether by draconian or consumeristic means, and to consider this deficit in a floating and nebulous way.

In this oversized-space, Reed’s videos read as cinematic, monumental, and lush. Although the artist’s statement equated historic witch-hunts with modern day consumerism and fascism, this connection wasn’t explicit in the video and this is a good thing. Keeping the narrative open allows the viewer to equate loss of agency with imagination, whether by draconian or consumeristic means, and to consider this deficit in a floating and nebulous way.

The dark beauty consistent in both Reed’s murals and videos draws parallels between the persecution, and also the magical power, of witchcraft with a violent conflict, where the state (or the church) imposes its will through terrorism to eradicate individual rights.

Though initially seeming to be light-hearted, Reed’s aesthetic acts as a smoke screen. It makes the disturbing subject matter oddly palatable, even cute, until you realize what you’re seeing. This realization makes their cuteness infinitely more creepy than any horror movie, and a metaphor for all those “nice” and upstanding members of communities who foisted violent terrors on women.

Except for one video, Witchual, Reed’s vision is distinctly devoid of humans, both the perpetrators and victims of witch-hunt violence. Instead, her blocky renderings of the objects of torture stand alone in bright pastel hues, and they seem ridiculous and benign at first. However, as your mind begins to understand the potential of each object, you realize their depiction mirrors the obtuse conformity required by ignorant, fear-filled societies. This contrast, between initial expectation and actual subject matter, makes the jolt all the more shocking and provokes a visceral response where disbelief and disgust compete with fascination.

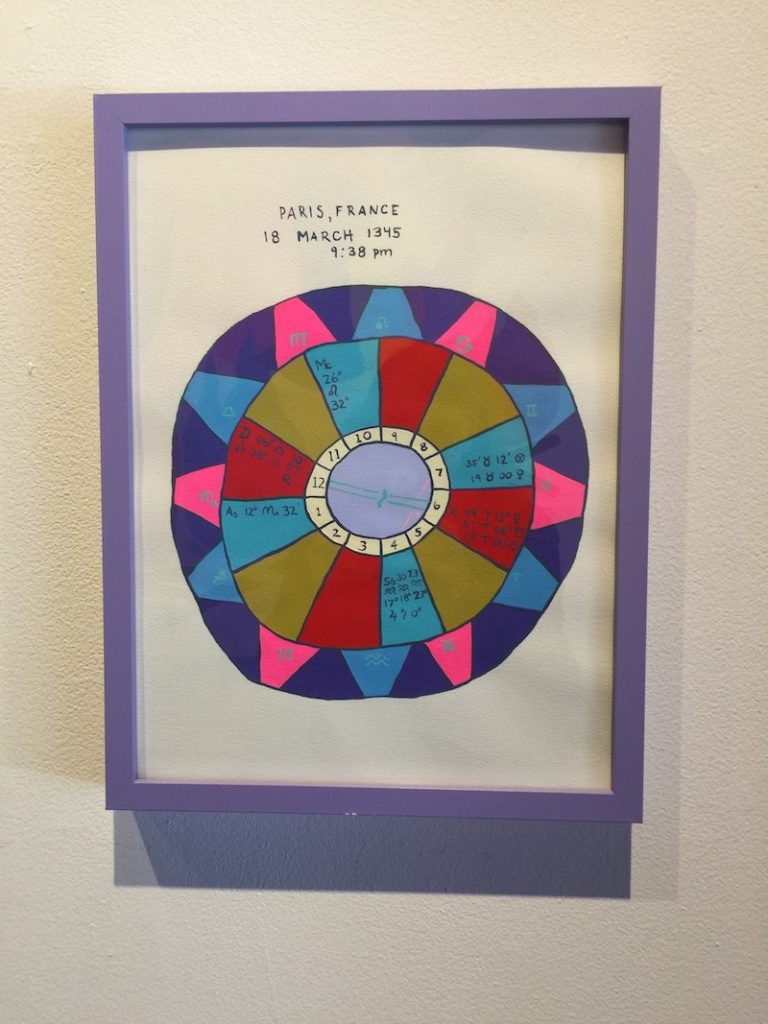

Although the show is a powerful, cohesive statement, there was one digression. A series of small paintings in purple frames fills one wall with works which seem like details from the larger narrative or studies for it. They’re small and sellable and consistent in Reed’s 1980’s palette of hot pink, purple, and teal. Rendered in a charming illustrative style, in their separation and smallness these works feel irrelevant to the rest of the show. They would be great for quirky greeting cards or T-shirts, or combined into a gif or video, but here, in contrast with the powerfully large murals and video, they are reduced to being merely cute and undermine the seriousness of their message.

Wandering through this exhibit, especially after reading the excerpts from Caliban and the Witch, I began to contemplate the very real human beings who were murdered and tortured in Europe and America after being accused of witchcraft. We have to believe they were not actual witches, just unusually creative, unique, or outspoken women, viewed as a threat to the Church and prevailing power structures. Most likely they were people like you and me, women who asked too many questions, questioned authority, and refused to stay in their place, making those in power uncomfortable.

Wandering through this exhibit, especially after reading the excerpts from Caliban and the Witch, I began to contemplate the very real human beings who were murdered and tortured in Europe and America after being accused of witchcraft. We have to believe they were not actual witches, just unusually creative, unique, or outspoken women, viewed as a threat to the Church and prevailing power structures. Most likely they were people like you and me, women who asked too many questions, questioned authority, and refused to stay in their place, making those in power uncomfortable.

While I feel lucky to live in a society where I can write these sentences without threats of violence, it’s terrifying to consider how easy it would be to return to such dark ages of ignorant manipulation. I can’t help but equate the historic persecution of women with today’s modern day witch-hunt, where blood-thirsty crowds chant “Lock her up! Lock her up!” and reproductive rights are the enemy, despite clear and scientific evidence that birth control, sex education, and access to abortion create more equitable and healthy societies.

It’s clear that those with such beliefs do not want equality for women, LGBTI, ethnic minorities, or anyone who is “other.” They want to return to dark times where superstition and male authority is unchecked and the rest of us are shameful and subservient.

In their cartoon shapes and childlike color, Reed’s depictions of gallows, handcuffs, and other historical items function as a compelling warning. Rendered as passive objects, these objects may seem initially silly, harmless, and obsolete. However, when plied by a bloodthirsty, unstable, or terrified mob, they become instruments of death and torture, designed to break the spirits of all women and turn them into submissive and exploited “producers” of children. Employed by those who claimed Christianity as their guide, Reed’s visions offer a sickening image of what human beings are capable of, and that the mysterious, creative power of “others” continues to threaten outdated patriarchs and their systems of power.

Now that we live in a new age where historical facts have become strangely irrelevant and our new President-Elect and his followers are attempting to relive the good ol’ days of repression for anyone who isn’t a heterosexual white man, it’s even more vital to remember Reed’s vivid cautionary tale. Women, and those who believe we are more than baby-making machines, must continue to fight for our rights as free human beings in order to guarantee that we never return to such times.

********

Author Cara Ober is Founding Editor at BmoreArt.

Macon Reed: Who’s Afraid of Magic? has been extended to Jan 2, 2017 by appointment. Contact ICA Baltimore for a viewing.