I’ll Eat When I’m Dead is a murder mystery set at a fashion magazine — full of designer gowns, powerful feminists, pills, and parties. It’s wickedly funny, but also manages to get to the heart of female relationships and the oppressive capitalist system that revolves around beauty and making women insecure.

Here’s a teaser from the official promo text:

When stylish Hillary Whitney dies alone in a locked, windowless conference room at the offices of high-concept magazine RAGE Fashion Book, her death is initially ruled an unfortunate side effect of the unrelenting pressure to be thin.

But two months later, a cryptic note in her handwriting ends up in the office of the NYPD and the case is reopened, leading Det. Mark Hutton straight into the glamorous life of hardworking RAGE editor Catherine Ono, who insists on joining the investigation. Surrounded by a supporting cast of party girls, Type A narcissists and half-dead socialites, Cat and her colleague Bess Bonner are determined to solve the case and achieve sartorial perfection. But their amateur detective work has disastrous results, and the two ingenues are caught in a web of drugs, sex, lies and moisturizer that changes their lives forever.

After reading a copy of Barbara’s new novel, and loving it, I reached out to her to find out more.

Can we talk about the genre of the mystery novel? I always picture old men reading dusty whodunnits when I think of a mystery…. So reading your book, full of young beautiful women in NY and pithy comments, was a shock to me.

Is it technically a mystery novel? If it is, I feel like you’ve completely changed my perception of what a mystery novel is and can be.

It is a mystery. I did that on purpose, for two reasons; one because I personally adore them, and two, in a mystery — whether it be highbrow or low, Miss Marple or Pale Fire — readers automatically keep their distance. There’s an immediate critique that takes place, the cataloguing of details and motives and implications; nothing can be taken at face value. As a result, mystery is a terrific format in which to grind out contemporary ethical debate.

I would also argue that the tired genre being reinvented here is not the murder mystery, but rather the book about clothes; the “girl book.” Personally, I *love* books, films, plays, etc. that revolve around clothes. I don’t get tired of the various iterations of Clueless or Heathers or Shopaholic (which is, at its heart, a pretty vicious critique of capitalism) and so forth, but I have grown, in the past ten years, extremely confused about where to shop.

Although it’s about beautiful young women working in a high fashion / materialistic / anorexic scenario – a sort of a girl fantasy – this novel feels quite feminist and the characters, although they seem too perfect to be likable at first, really grow on you. I love the house in Brooklyn, the ritual of cooking dinner, the partying, casual hook-ups… and the importance of female friendships at the heart of this. That subtext grows unexpectedly as well.

Can you talk about your interest in feminism, female relationships, and high-powered young women who aren’t afraid to make mistakes? Also, for you, the meaning of beauty in American culture – specifically female beauty – and what that power is and does?

I am an American woman, and I have a relatively large amount of power over my own life, and I *love* to get dressed every morning. I’m free to wear whatever I please. The act of choosing my clothing and makeup, regardless of what direction it may take, feels to me like self-expression; it feels like a creative and emotional act in which I tell other people something about myself.

On the other hand, fashion and beauty costs me everything. I’m already earning 78 cents on my husband’s dollar, and then I’m choosing to spend *at least* another 20 more of those cents–and precious hours every morning, when men are playing squash and networking and I’m curling my hair instead–to decorate myself for a world that struggles to validate even the wealthiest, most powerful women’s interiors.

After reading this, I have so many thoughts about the fashion industry and it’s contrasting values of ‘shallow’ beauty and the editor of RAGE’s very true assertion that is it a billion dollar industry and creates livelihood for millions of people. What an amazing vision — that a women’s fashion magazine could transform a horribly abusive and bad for the climate industry into an ethical system that empowers the powerless and protects the environment. Do you think this could really ever happen? is it happening anywhere? Or is this just fiction?

Certainly, in our real world, there are no ethical fashion publications as powerful as the one depicted in the book, though ethical retailers and directories abound. It would be incredibly challenging to build a business on this moral highground, because quite simply there are no inexpensive ways to track and control a supply chain from fabric to storefront.

Consumers, too, are really used to cheap and trendy clothing, so how do we go backwards from that? It also seems worth noting that the buzzword of ethical consumerism is both powerful enough and empty enough to enable even H&M to participate in “conscious” labeling, patting itself on the back with one hand while selling $25 billion dollars worth of landfill-ready clothing annually. So no — I don’t think this could actually happen. It is an absolute fantasy on my part.

Well, it’s a fantastic fantasy. It’s exciting to envision what the fashion industry could accomplish in the world, and to appreciate the massive power of its revenue stream. How do you fit into that world in your own life?

I’m being enabled by a massive global economy that thrives on the backs of the world’s poorest women; the garment industry pollutes their drinking water, controls their economies, and keeps them subservient from the cradle to the grave, all so I can have a cheap new top for that meeting on Wednesday. I’m also being manipulated in that process by the twin behemoths of marketing and advertising, which encourage us to spend spend spend in pursuit of what are deliberately unattainable ideals of fashion and beauty.

And so if I don’t meet those ideals–which of course I never do, because they have not been created for me to attain them and potentially stop spending–my self-esteem takes a wallop. But that same self-esteem gets picked back up the moment I wake up again and wear a denim palazzo jumpsuit and feel all day like I am fishing off the coast of Sardinia in 1970, or whatever identity it might conjure up. And that is extraordinarily powerful stuff.

It’s hugely powerful! And also a great reminder of the significance of material culture – the things we buy to wear, especially.

These are all things that we think about when we think about clothing. I’ve had *thousands* of conversations about this with my friends, and that comes back to your friendship question–this is a book I wrote, as the dedication says, for my friends. I wrote this book for the brilliant women I know who are constantly grappling with the prism of this burdensome diamond of fashion and beauty.

And as a result the women in the book are of course kind to each other in the way adult women learn to be kind, and they’re kind because I’m also sick to death of reading books where women are mean to each other. The catfight is a plot point that I find personally offensive, especially catfights that revolve around fashion–that’s just women policing each other for the hypercapitalist patriarchial nightmare in which we live, and fuck that, it’s boring, I won’t have it, it’s narrative antifeminism.

It’s interesting to consider the ways that capitalism and feminism can work together… Basically, that women own and harness this system for their own gain on their own terms. It’s a powerful vision and one that, weirdly, makes sense to me because it encourages people to keep making the bad decisions they’re already making, economically, but these decisions actually clean up the environment or insist upon paying a living wage. Ethics have been somehow made sexy in this vision!

Let me say that I am genuinely interested in commercialized feminism; I am genuinely curious about whether or not we can buy our way into a better society. I am genuinely curious about what it means for magazines–and any form of women’s media–to declare themselves feminist, but fill their pages with pictures of rich women’s bodies, and showcase clothing that is made by extremely poor women. What women are served by women’s media? Why can’t we look away from Vogue? Why doesn’t Ms. make more money, why does Bitch Media have to survive from donations?

I love the language and humor, the artful prose, of this book. Your prose is playful yet specific and the language is colorful. It’s a pleasure for my brain, very sensual. Can you talk about your favorite authors and artful prose? Who has influenced you and who are you reading now?

Like all writers, I am a collector of words, and a voracious reader. I did write up a list for Read it Forward of the books that I read while writing this novel, and it’s here. Generally, when I’m writing a book, as I am now, I read more nonfiction than anything. I’ve been devouring books on the business of technology — The Everything Store and The Upstarts, both by Brad Stone, Whiplash by Joi Ito and Jeff Howe, and Disrupted by Dan Lyons are all recent favorites in that department — but I also completely loved two memoirs and have been telling everyone I know to read This Close to Happy by Daphne Merkin, which is the best book on suicidal depression you will ever read, and The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy, which came out of her essay in the New Yorker, Thanksgiving in Mongolia. I’m also in the middle of Double Bind, which came out recently and is an edited volume of essays by women on the subject of ambition.

Can we talk about the combination of anorexia and fashion? I am alluding to the title of your book, of course, but also the idea of beauty and health.

The title of the book is a quote from Daphne Guinness, who is both a billionaire heiress and one of the most stylish women on this planet. If you were in the business of judging a book by its cover, I think you would honestly look at her and believe completely that she is a brilliant, fascinating artist who is rolling in self-confidence.

Certainly as someone younger than she is, I would absolutely assume, wow, you rock an inverse Cruella de Ville bouffant and hoof shoes and a cape, you must have a metric ton of self-love.

I’m not being ironic. Yet, she was quoted saying “I can’t eat when I’m working … I’ll eat when I’m dead,” in a profile for The New Yorker and it really struck me–that someone with so much money and power, and such an obviously creative life, is still beholden to the lie that being thin is important.

And I don’t think anyone is exempt from that lie. It surrounds us. Even if we don’t believe it, we are bombarded, daily, on every platform, by ads for weight loss, pictures of thin bodies, by a culture of self-improvement that can be exhausting to fend off. And so, the book is, I think, in some way, trying to explain how educated women with money and power still manage to feel that way about their bodies.

There’s also a quote from the novel that I recall, about beauty being pain. I find myself questioning what that means and who this system helps? And why do you think human beings so ingrained with all of this?

Literally, how many times do we hear that phrase, when we’re having hair ripped from our bodies or bleach burning our scalps or talking about working out or whatever, and we laugh and say, totally, and yet, it is absurd.

I think the notion that beauty is valuable starts here: we believe that beauty helps women gain economic security. For thousands of years this has meant marriage, but that is less true with each passing year–certainly most married women need to work for a living. Many of us also believe that beauty is power; that it makes other people like us more, that being beautiful helps us move through the world, that it eases, somehow, the exquisite pain of existence. The economy in which we live benefits very strongly from these beliefs — consider the trillion-dollar sizes of the fashion and beauty markets– so they are constantly reinforced, in advertising and marketing that worms its way into all varieties of discourse.

Thanks for the interview and congrats on your book! I loved it.

**********

Author Cara Ober is founding editor at BmoreArt.

Photo Credits: B&W Headshot by Dennis Drenner

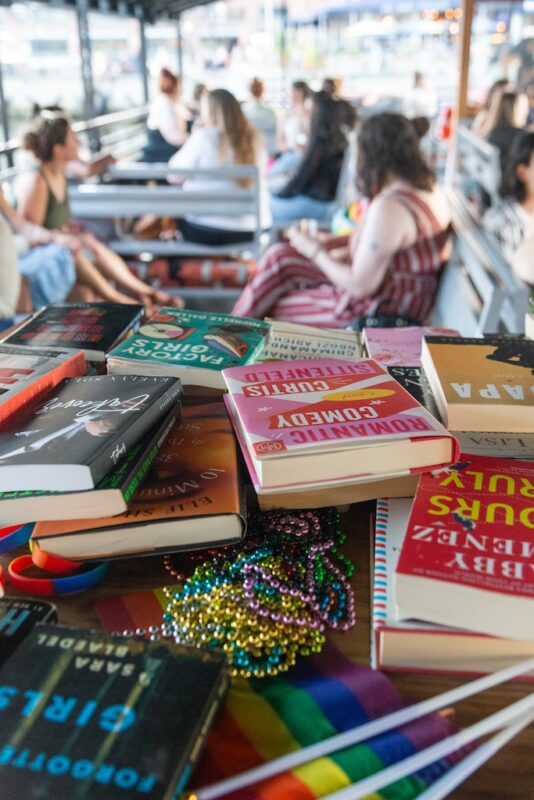

Event Flyer for Bird In Hand Book Launch

I’ll Eat When I’m Dead Book Launch

Wednesday May 3: 7.30-8.30

Bird in Hand

11 E 33rd St, Baltimore, MD 21218