Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley to Paint National Portrait Gallery Portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama by Cara Ober

Although the news of Amy Sherald’s Michelle Obama portrait commission at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) was not a surprise to everyone in the Baltimore art community, the official announcement of Sherald, along with internationally famous painter Kehinde Wiley, as the Obamas’ portrait artists is fantastic news.

Sherald, a 2004 MICA MFA graduate, is based in Baltimore, and will paint former first lady Michelle Obama while New York-based Kehinde Wiley will paint President Barack Obama. The paintings are scheduled to be unveiled in February, 2018 and added to the National Portrait Gallery’s popular collection of presidential and first lady portraits.

“Both [painters] have achieved enormous success as artists, but even more, they make art that reflects the power and potential of portraiture in the 21st century,” said Kim Sajet, director of the NPG in a statement.

The Wall Street Journal broke the story yesterday and pointed out that Wiley and Sherald are the first black artists commissioned to paint a presidential couple for the National Portrait Gallery. This mention is hugely significant; it predicts a seismic shift in a culture where museums have historically displayed few black faces on their walls and even fewer black artists.*

Left: Kehinde Wiley, photo by Kwaku Alston, © Kehinde Wiley Studio. Right: Amy Sherald, © 2017 Amy Sherald.

Left: Kehinde Wiley, photo by Kwaku Alston, © Kehinde Wiley Studio. Right: Amy Sherald, © 2017 Amy Sherald.

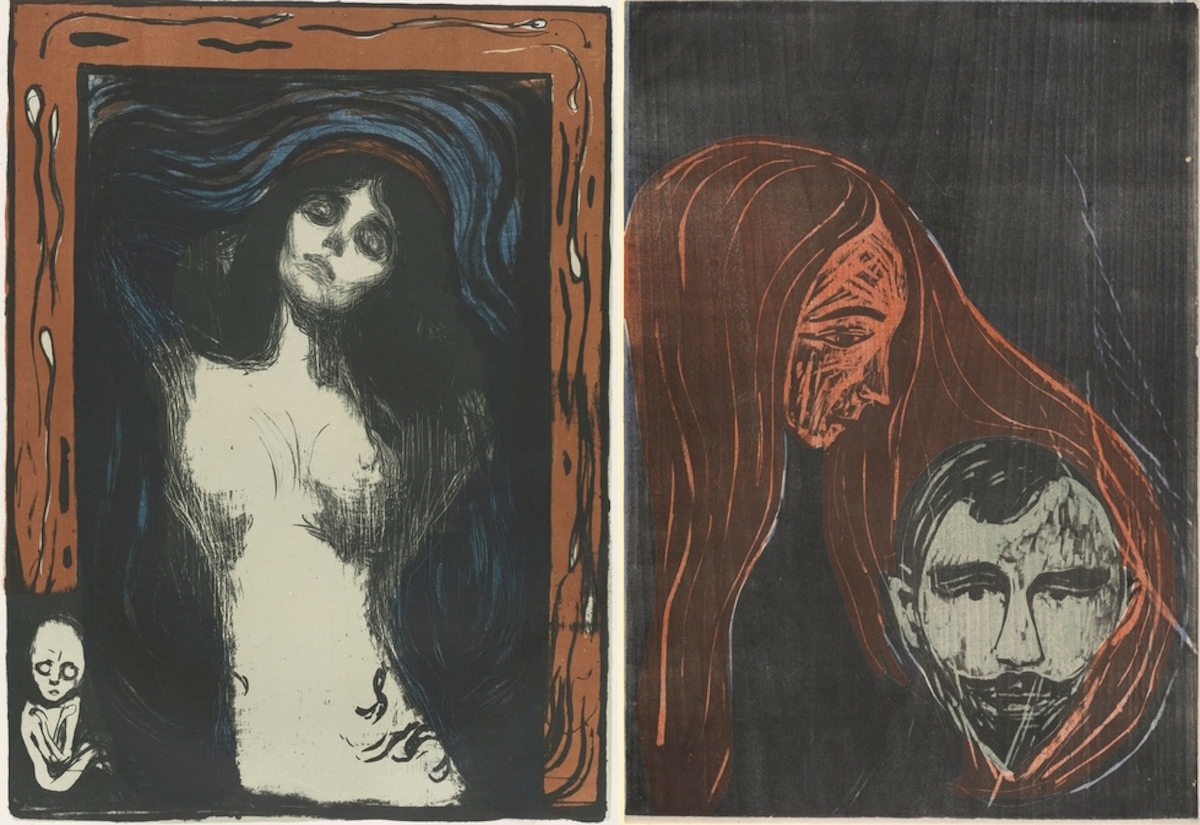

I explored this issue, which has been at the forefront of Sherald’s work as a portrait painter in “The Face of Figurative Black Art,” a review of Sherald’s group show, About Face, at Creative Alliance in January 2017. Then as now, Kehinde Wiley was an apt comparison to Sherald, an appropriate partner in this new project.

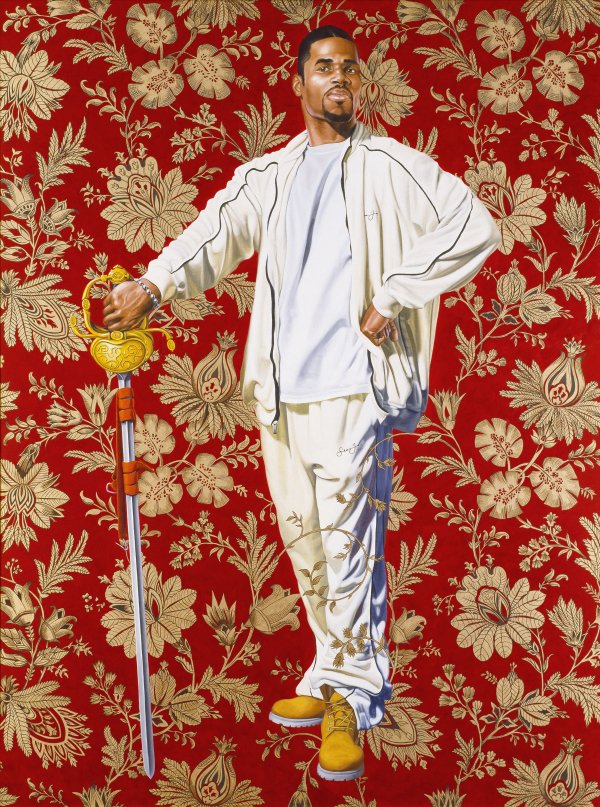

“Even today, in the age of an Obama Presidency in the US, it’s shocking to realize how few depictions of black figures appear in major museums, but it is encouraging to find contemporary figurative artists who are now substantially filling this void. Kerry James Marshall, whose retrospective Mastry is on exhibit at the Met Breuer until the end of January 2017, is perhaps the most visible contemporary painter who creates portraits of black figures with exaggerated, ebony-hued skin in order to expand and challenge the art historical cannon. In his wake, a number of young African-American painters have taken up the cause and achieved international success like Kehinde Wiley, working within a rich tradition of European figurative painting to depict black faces and bodies in art historically significant ways.

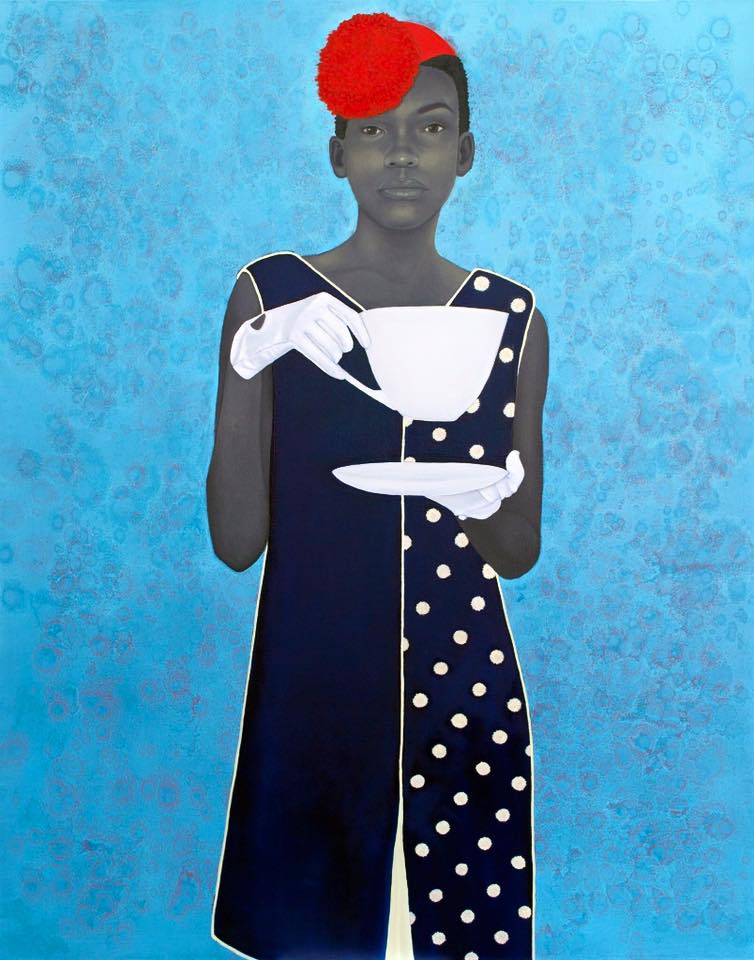

“Baltimore’s Amy Sherald, the first woman to win the National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Competition and a resident artist at Creative Alliance, is another such painter. Joining her in About Face, an exhibition in the Creative Alliance’s main gallery, are contemporaries Rozeal, Ebony G. Patterson, and Tim Okamura. The result is a delightful mishmash of styles acknowledging a diverse range of contemporary figurative painting options specifically for and about black subjects. Despite the narrow genre of portraiture, the show is ambitious and varied enough to suggest a radically expanded future for an art historical cannon where black faces and figures are the rule, rather than an exception.“

If you consider such artists, including Wiley and Sherald, within the context of a larger art historical cannon, their selection as presidential portrait painters is no less miraculous than the election of our first black president.

Amy Sherald’s Welfare Queen (2012). © Amy Sherald 2017

Amy Sherald’s Welfare Queen (2012). © Amy Sherald 2017

Institutional aesthetics have been deeply entrenched since this country was founded to intentionally favor white subjects with very few representations of black ones, to the point where a visit to any historical American museum would suggest that our country had very few, if any, African American citizens. An example of early racial comparisons is outlined in great detail by President Thomas Jefferson in the tome Notes on the State of Virginia, where he compared the “share of beauty” between the two races, saying that:

“Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions of every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immovable veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race? Add to these, flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form, their own judgment in favour of the whites, declared by their preference of them, as uniformly as is the preference of the Oranootan for the black women over those of his own species.”

The statement by one of America’s beloved founding fathers, outlining the superiority of white skin, intelligence, and beauty over black is an explicit reminder of the centuries of oppression that African Americans have suffered, it’s matter-of-factness proof of why it’s taken 250 years to reach a point where our national cultural institutions can finally say that Black is Beautiful–and mean it.

This is one reason that Sherald has often cited as motivation to create her portraits: to see someone that looked like her on a museum wall, to recognize her value within society and culture production. The presence of the Obama portraits at the NPJ, as well as Sherald’s and Wiley’s names on the wall, is a significant historic event that should be celebrated as a turning point in art history.

Photo from BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas: Issue 01, portrait by Justin Tsucalas

Photo from BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas: Issue 01, portrait by Justin Tsucalas

This announcement is also a significant career changer for Sherald, who has worked tirelessly for the past ten years, teaching incarcerated inmates in Baltimore in her spare time and enduring a terrifying health crisis. At age 39, Sherald’s heart failed and she spent months in the hospital waiting for a transplant, which was successful but requires huge amounts of medication for the rest of her life.

The WSJ called both artists “rising stars,” but it’s obvious to anyone with eyes that Wiley is already an international superstar. As ArtNews noted, “Sherald is less well-known than Wiley.” Although Wiley is a known quantity, Sherald’s star is still rising, a fantastic position from which to grow.

Sherald has had two recent shows with Monique Meloche Gallery and is planning a solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis. She is currently featured in the Studio Museum in Harlem’s Fictions, featuring 19 emerging artists of African descent, and her work is in the permanent collection at the National Museum of African American History and Culture and National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Both Wiley and Sherald take inspiration from the portrait paintings of Old Masters, working large with and placing their models into imagined settings, with Wiley’s baroque and full of elaborate pattern and Sherald’s loose, with dreamy washes of color. In both cases, their work blends with established traditions of classical portraiture, but also challenges and expands it by representing empowered black figures on the canvas.

In 2012, Wiley, whose recent activities include a 2015 solo show at the Brooklyn Museum and a US State Department Medal of Arts the same year, told BBC News, “The reality of Barack Obama being the president of the United States—quite possibly the most powerful nation in the world—means that the image of power is completely new for an entire generation of not only black American kids, but every population group in this nation.”

And now, both Sherald and Wiley are an important part of this legacy.

*Please note that Simmie Lee Knox painted official White Portraits of Bill and Hillary Clinton and was the first African American ever commissioned for a presidential portrait. However, this is not the same as the official portraits commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery of outgoing presidents and first ladies.

Amy Sherald will give a free talk at 5:30 p.m. Oct. 26 in Room 101 of the F. Ross Jones Building, Mattin Center, on the Homewood campus of Johns Hopkins University.