Baltimore Artists at Elsewhere, an Artist Residency/ Museum housed in a former thrift store in Greensboro, NC by Michael Anthony Farley

Porcelain cats jailed behind chicken wire. Tiny knives and cigarette lighters suspended from fishing line, jiggled in place by a fans. Plastic dollhouses containing surreal domestic tableaus.

These are just a few of the dioramas Beau Vasseur composed from found objects in his recent work “Department No. 1,” installed as part of Baltimore Goes Elsewhere, in Greensboro, North Carolina. Vasseur’s work parodies “the ridiculousness” of the consumer experience and the aesthetics of shopping. But I read it mostly as a celebration of all the inexplicable objects people hoard. It’s a buffet of second-hand junk, sourced from a collection that spans decades—a thrift store collection that’s available to artists to reuse and remix in strange and wonderful ways.

Of all the real and imagined places Baltimore has lost over the past decade—countless artist-run spaces, brutalist civic structures, the long-awaited Red Line, sleazy queer after-hours speakeasies, to name just a few—I’ve probably quietly missed the Village Thrift on North Avenue the most. Because the humble thrift store is a microcosm of everything that makes cities liveable and loveable, from cotidian accessibility and convenience to that wondrous feeling of discovery that comes from encountering something unexpected or inexplicable. It’s one of the few sites of consumption where the cruel “logic” of capitalism gloriously unravels at every level. Mostly, it was nice being able to walk somewhere to buy essentials such as pots and pans for under $5, and fantastic to stumble across gems like a glittery purse in the shape of a sneaker.

The reality of living without a central thrift store sucks. Living inside a thrift store, on the other hand, is a dream come true. I know this firsthand, because this summer I was fortunate enough to spend a weekend as a visiting artist at Elsewhere, an artist residency/museum housed in a former thrift store in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Elsewhere has been an arts space since 2003, when Executive Director George Sheer took over his family’s long-vacant thrift store and the treasure trove of bizarre and/or useful materials it contained. Since 2005, the nonprofit has hosted artists from around the world for residencies—offering its stockpiles of vintage fabric, books, toys, and more for experimentation and collaboration.

This summer, five artists from Baltimore spent four weeks living and working with the collection, mining it for materials and inspiration, and ultimately creating pieces to live on indefinitely in the ever-changing museum. From August to September, Baltimore-based artists Antonio McAfee, April Camlin, Beau Vasseur, Gina Denton, and Hamida Khatri (full disclosure: I was a selection advisor along with Deana Haggag) lived and worked together in the space.

I got to join the residents (along with fellow Baltimore visiting artists Ginevra Shay and Jackie Maria Milad) just ahead of the group’s new works opening to the public. My long weekend at Elsewhere is one of the most memorable art/life experiences I’ve ever had. From the closets of vintage clothes open for impromptu games of dress-up to the communal meals and years of up-cycled art projects integrated into the live-work space, Elsewhere feels singularly utopian and playful.

The model of “such a highly functional collective living situation,” as April Camlin described it, was an integral part of the studio process. Camlin was inspired by “the ways in which art was incorporated into living… the kitchen as an installation, group meals as performance… sustenance and abundance were elevated and yet not in a lofty or precious sense. This truly is a ‘living institution’, a place where you grew to feel that anything was possible. I felt so enveloped in genuine warmth and acceptance there! It was especially empowering for me to work in their woodshop, after repeated experiences with the general misogyny of shop and makerspace culture, it felt expansive to work in a space free from judgement, where I felt liberated to learn and experiment on my own terms.”

Hamida Khatri echoed that sentiment. Originally from Pakistan, Khatri appreciated the opportunity to challenge her comfort zone both socially and professionally: ”Back in my country, girls are not taught how to use machinery or tools as they are for only boys/men to use. For many of my things, like framing an artwork, I had to go to the framer owned by a man who had staff (also including men) who made customized frames.

Coming to Elsewhere, I challenged myself—even though I was shit scared—to use the power tools like the drill, miter saw, and the nail gun. I was totally freaked out about them all, but there were people around me who helped me get over the fear and showed me how to use them and were there to witness me using those power tools. So, all in all my experience at Elsewhere was truly liberating in terms of expanding my art practice and the tools that I use now to for my artmaking.”

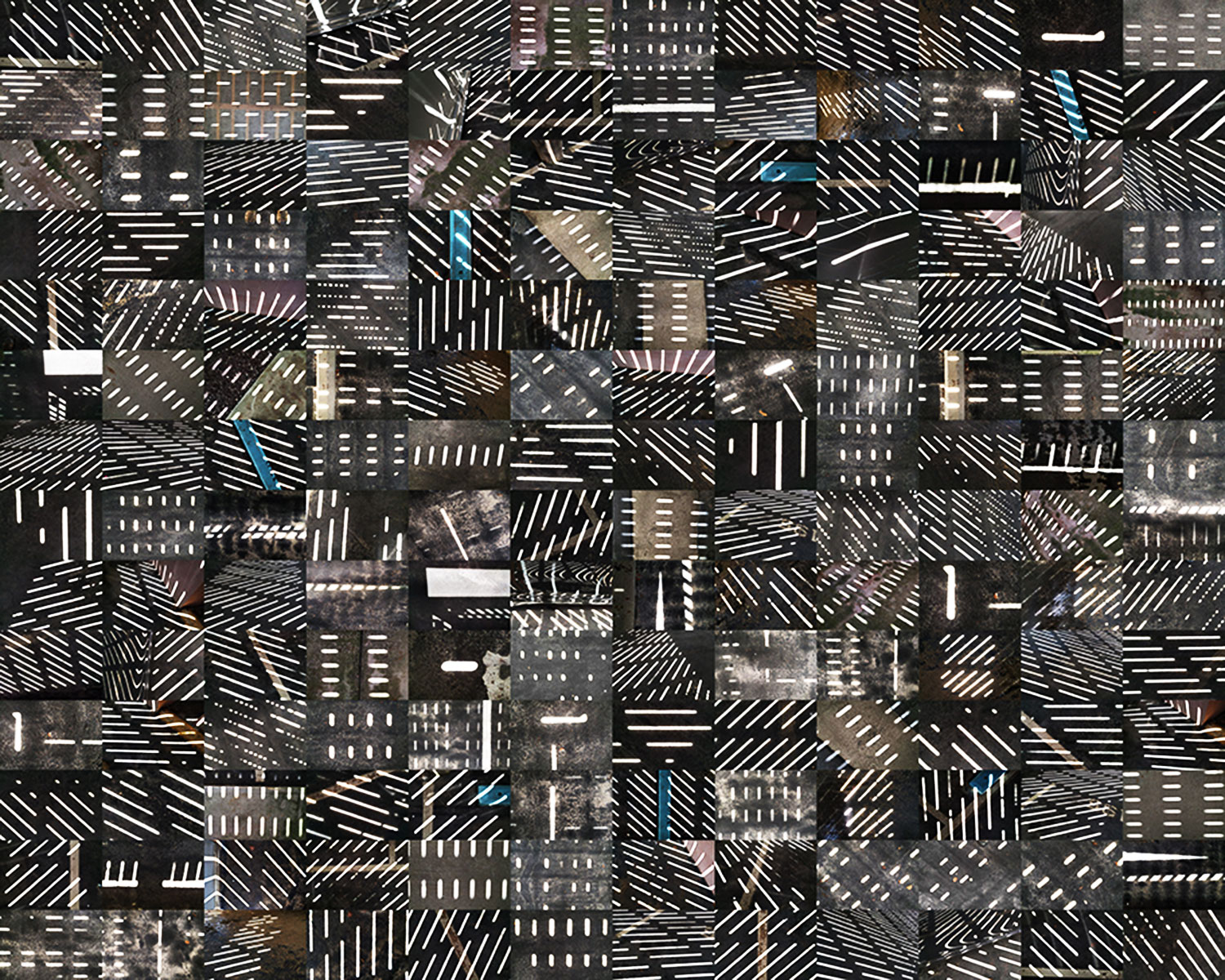

Khatri’s principle piece developed at Elsewhere, ”City of Scraps”, introduced woodworking to the wide repertoire of media she utilizes in her socially-minded practice. The small cityscape incorporates lights, evoking a nighttime view from a window. The rag-tag urban environment is intended to evoke the socioeconomic divides evident in both Pakistani and gentrifying American cities, as well as the constant state of reinvention and reuse in the museum’s ever-changing collection. In both references, it speaks to “the left behind memories of an old place”.

The other artists in the program, Antonio McAfee and Gina Denton, worked in their preferred mediums of photocollage and fibers, respectively—taking advantage of the residency’s vast archives of material. In both instances, the artists considered the gregarious/quasi-public nature of the site and incorporated an interactive component to their studio practices.

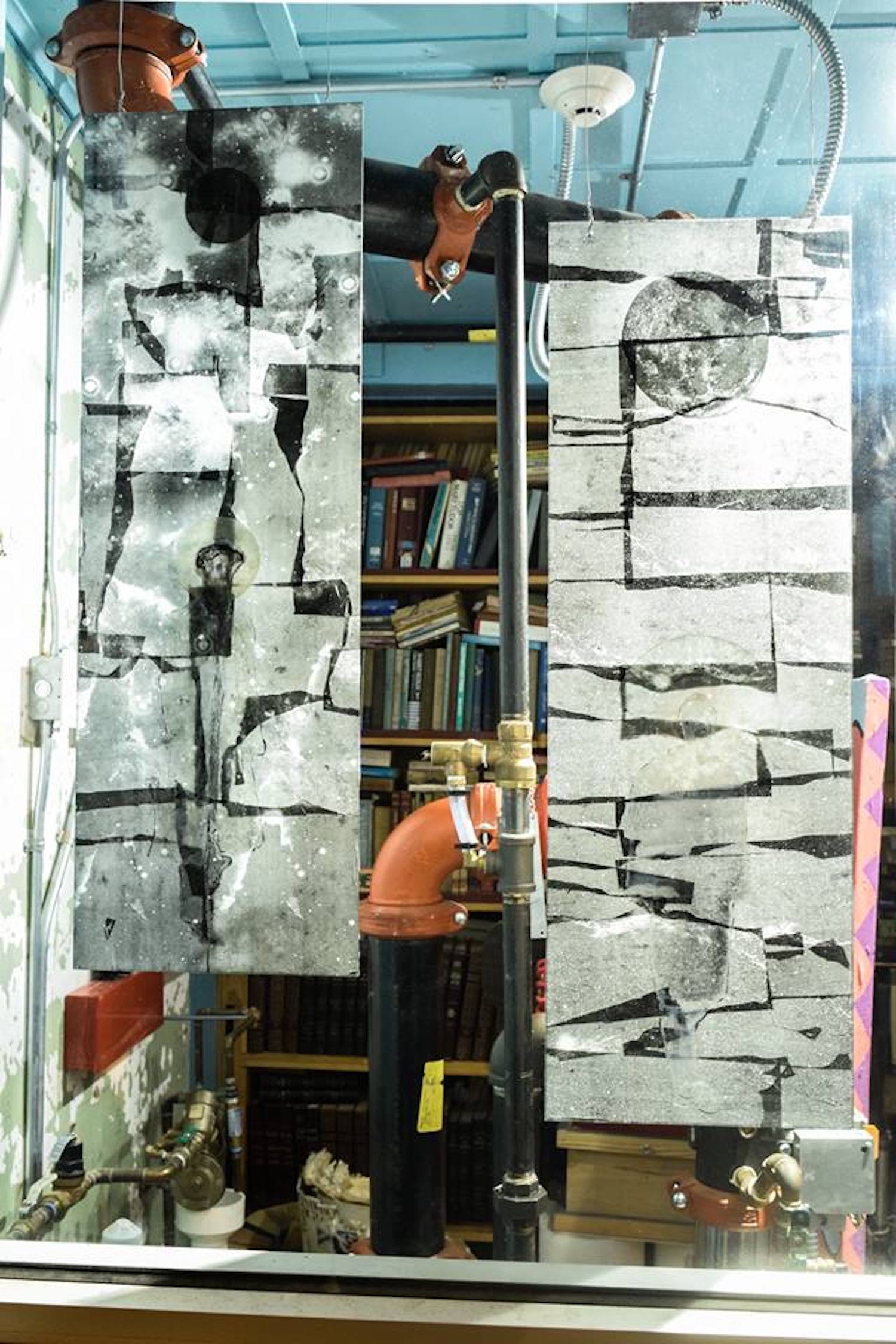

McAfee mined Elsewhere’s library for imagery to create collages of the Greensboro Four sit-in protesters—Jibreel Khazan (Ezell Blair Jr.), Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond—in his signature acrylic medium transfer style. These transparent tableaus imagine a new cosmology for the civil rights activists, contextualizing them as quasi-religious figures against the night sky (a reference to Baltimore’s decision to quietly remove Confederate monuments under the cover of night). The series, “The Breaks in the Game” was installed on glass panels in the museum’s storefront windows, evoking stained glass, and speaking to history’s mutability as it’s retold, repeated, or mythologized. The works addressed passers-by from the street, and in the library itself, visitors could get a behind-the-scenes look at McAfee’s process.

In “Big Girl Wanna Play Too,” Gina Denton responded to Elsewhere’s culture of dress-up play, hoping to establish a precedent for wearable sculpture at the museum:

“I noticed a void, and I wanted to fill it. So, part of my piece was a line of plush wearables made from the scraps of my larger sculpture. I made this, in part because I noticed that aside from the occasional costume performance relic here and there in the wardrobe, there wasn’t, or didn’t seem to be a tradition of artists making wearable pieces from a functional fashion perspective for the collection.. and since Elsewhere is this museum that so pushes the boundaries between art practice and living practice, and residents are encouraged to dress up in Elsewhere’s existing wardrobe on the day to day, I thought it was crucial to leave pieces that were functional as fashion as well as having deeper poetic meaning in context with my project as a whole. I wanted to start a tradition of future artists making couture pieces for the collection, from the collection. I also want for future residents to find these pieces, and find joy in them simply because they want to, and can wear them out on the town. I chose the form of a necklaces because they are something that any body can wear regardless of size.”

The sculpture comprises plush rings sewn from Elsewhere’s enviable collection of midcentury fabrics. When stacked, they form a figure-like totem. Situated in the museum’s “Transformatorium,” visitors are encouraged to try them on “as an abstract fat suit. How does one interact with the wardrobe with five extra inches around one’s waist/arms/legs?”

The sheer volume of material available for fiber artists at the residency is inspiring, but also overwhelming. April Camlin tackled Elsewhere’s mountainous pile of ribbons, attempting to restore a semblance of order to the collection of material. Sylvia Gray, George Scheer’s grandmother, had collected untold thousands of ribbons during her life as the thrift store’s proprietor, meticulously winding them around pencils for storage.

When April arrived at the residency, she grappled with the chaotic, unwound mounds that filled “The Ribbon Room” as well as her role in the larger story of the institution: “It’s intense because you have to make space for yourself by moving or dismantling other artist’s work, and that can be difficult to come to terms with. I was confronted by my own footprint in the institution, which was why I ultimately gravitated towards a project that generated a resource for future residents. It’s such a unique opportunity because you know that whatever you leave behind will likely shift and become a part of a different project…you can’t control the future life of your work.”

Camlin’s resulting project, “To Climb the Mountain”, saw her wash, wind, and store roughly 3,000 ribbons. She constructed a plexiglass storage vessel, in which the newly restored bobbins could be easily accessed (or added to) by future residents or staff. The gesture speaks to Camlin’s interest in labor and obsessive process, but also to the generosity of spirit Elsewhere inspires—equally in line with Camlin’s own meticulous, system-based practice and a desire to gift a service to future users.

Generosity is an impulse that’s inescapable at Elsewhere. Perhaps that’s because it’s one of the few art spaces that casually screams “overabundance” in contrast to the preciousness or scarcity implied by conventional museum aesthetics. Here, the absurd material detritus of consumer society is reconsidered outside of traditional notions of “value”. But mostly, the culture of the institution inspires utopian thinking. Of all the resources I lusted after at Elsewhere—stacks of reclaimed wood, bolts of midcentury fabric, racks upon racks of vintage gowns—the social dynamic sticks with me most saliently.

In an era where gentrification, government crackdowns, and countless interpersonal challenges threaten under-the-radar collective live/work spaces, Elsewhere remains a shockingly functional (and public!) model of living and artmaking together. The artworks produced as part of Elsewhere’s residency programs will remain in the Greensboro museum indefinitely, but I’m happy to report that more than half-a-dozen Baltimoreans are bringing back some serious inspiration.

Click here for or more information about Elsewhere.