An Interview with Mequitta Ahuja About Success, Heartbreak, and a Recent Guggenheim Award by Cara Ober

The July 24, 2017 issue of the New Yorker described Mequitta Ahuja‘s work, then on view at the Asia Society Museum, as “whip-smart and languorous.” According to the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, where she was just named a 2018 Fellow, Mequitta Ahuja’s works have been widely exhibited, including venues such as the Brooklyn Museum, Studio Museum in Harlem, Saatchi Gallery, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Crystal Bridges, Baltimore Museum of Art and Grand Rapids Art Museum. Ahuja, a Baltimore-based artist whose parents hail from Cincinnati and New Delhi, has long employed her own image to challenge historic traditions of portrait painting.

I caught up with the artist to ask about her momentous Guggenheim award, announced April 5, 2018, and to discuss the new opportunities and ideas abounding in her studio.

Portrait of Ahuja in her studio by Justin Tsucalas, for the

Portrait of Ahuja in her studio by Justin Tsucalas, for the

BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas: Issue 02

What led you to apply for a Guggenheim fellowship? What was your reaction when you found out you got it?

First of all, Cara and everyone at BmoreArt, thank you for doing what you do. I’m grateful to be a part of a vibrant community of artists and creative thinkers, and thank you for giving me space to tell my story. Some of you already know this story, but I feel compelled to tell it again.

My experience with the Guggenheim is tied to my experience with the Sondheim prize. I originally decided to apply to the Sondheim because my hermetic tendencies had left me feeling isolated. I thought participating in the Sondheim exhibition might help me be a part of things so I was delighted in 2015 when I made it to the final round. The night of the award ceremony, I was disappointed not to win, but I was also genuinely happy for the winners, and I felt that I had fulfilled my intention. It was through that exhibition that I first met many of the people who would eventually become my friends. After the ceremony, my husband Brian and I attended a dinner party with some of the finalists and other local artists.

We had a great time, but the night would not end well. Those couple of months had been intense. I’d married in April, got pregnant in May, and had worked double-time on four new paintings for the Sondheim show. The night of the award ceremony, after the party, I had a miscarriage. By early morning, I was in an ambulance to Mercy hospital. After many hours of trying to stabilize my blood pressure, my doctor performed emergency surgery and a blood transfusion, saving my life. The experience was traumatic, and for a while, it eclipsed everything else. But two years later, I was ready for a do-over. By now, the Sondheim had taken on a unique psychic charge.

With a new intensity, I was again a finalist for the Sondheim in 2017. I applied to the Guggenheim in large part because I lost the Sondheim that second time. It was one of several applications. I was trying to fulfill this thing that felt unfinished – at least the part I thought I might have some control over. My initial reaction to learning I’d received the Guggenheim fellowship was surprise bordering on disbelief. Since I didn’t think I had much of a chance, I hadn’t set my heart on it. It’s strange to get something you didn’t let yourself want, so at first if felt unreal, but then, like anything, it found its place in my story.

Sales Slip, Oil on Canvas, 84”X80” 2017

Sales Slip, Oil on Canvas, 84”X80” 2017

I’m so sorry you had to go through that and also incredibly inspired by your candor and determination. Thank you for sharing your story. Can you talk a little bit more about your goals and strategy in applying for the Guggenheim?

In the past, I’ve avoided applying to project-based grants. The project framework doesn’t fit my approach of working year after year in a single medium on one continuous set of themes and problems, but it finally occurred to me to make a simple maneuver that any artist working as I do could perform.

Since my artist’s statement already contained the necessary elements, including a clear goal – “My central intention is to turn the artist’s self-portrait, especially the woman-of-color’s self-portrait, long circumscribed by identity, into a discourse on picture-making, past and present” – for my Guggenheim application, I took my artist’s statement and reworded it in the future tense. The fact that I may well be working on this “project” for a lifetime as opposed to the yearlong duration of the fellowship is a benefit not an obstacle. Starting on day one of the fellowship, everything I do in the studio and every exhibition, including my solo show which opened last week in London, Notations at Tiwani Contemporary is part of my “project.”

What was the impact of the Louis Comfort Tiffany grant, awarded several years ago, on your career trajectory? How do you envision the Guggenheim grant impacting your career? What does it mean to you to have received it?

The impact of these kinds of awards –the Tiffany, the Guggenheim, the Sondheim, is three-fold–status, money, and validation. As artists, we figure out how to work when any or all of these is in short supply. If we’re lucky, we get occasional infusions of one or another, enough to keep us afloat. While I’ve been lucky to have that, the last few years have been difficult. After the miscarriage and month after month, year after year of disappointment, I’ve been distracted by a depth of sorrow I hadn’t previously known. I think I’ve been in mourning. This has impacted every area of my life including my art, and it has opened a host of existential questions about my choices, my luck, my purpose.

How do you keep yourself constantly moving forward?

My studio mantras “trust the process” and “the work is the reward,” could not compete with my despair. For me, the most profound impact of any of these kinds of prizes (when you get them and when you don’t) is always existential and psychological – they contribute to the shape of the story we tell ourselves, about our efforts, our lives, our purpose and those stories are either fuel or weights. At least that’s been my experience.

The Guggenheim fellowship fulfills the need I have to redeem the story of these last few years, and that fulfillment makes me a better painter. I felt it yesterday when I was in the studio. The fellowship gives me that little bit more confidence. Now that I’ve received the award, however, I have to live up to it. I have that much more to prove.

In the Studio: Fingering Vanitas, Seated Scribbler and A Real Allegory of Her Studio

In the Studio: Fingering Vanitas, Seated Scribbler and A Real Allegory of Her Studio

As your career grows to an international level, do you think you’ll stay in Baltimore?

Have you listened to the podcast S-town?

YES!

Remember the part at the end when John B says something like… from this small patch of land, I have become a global citizen. That’s the way I feel. I live in Baltimore, and I rarely travel, but this month my work is in Hong Kong, Brussels and London, and I am currently working on a Fall solo show in Milan. The fact that I can do that from here is very satisfying. In both people and landscape, Baltimore is a diverse urban space. It’s a city where it’s possible to have a backyard, and as person who grew up in the woods, that’s important to me.

Why do you live here and what do you see as the advantages and disadvantages for an ambitious artist?

How I got to Baltimore is the same as how I got to everywhere else I’ve lived as an adult. My work paved the way. Earlier, I’d moved to Chicago from the Berkshires when I got a fellowship to attend graduate school. From there I moved to Houston because I got accepted into the Core Program. Then I moved to NY as an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem. I was walking along the Hudson river when I got a call inviting me to be a painter in residence at MICA, so I moved to Baltimore.

Three days into my residency, I met Brian Weir. He was completing his PhD in public health at Johns Hopkins. At the end of my yearlong residency at MICA, Brian asked me to move in with him. He’d bought a house in Baltimore five years prior. Now, Brian is a scientist at Hopkins, and we married in 2015. While the house has lost property value since first purchased, we love it. It’s spring and we’re pursuing new garden projects. Our neighborhood is friendly, quiet, and diverse. Also, we’ve continued in our efforts to have a child. After three failed IVF attempts, we still have frozen embryos at the Johns Hopkins lab.

With job, home and medical expertise, we have a number of things tying us to Baltimore. That said, my studio is very small for the size of my paintings. It’s a constant fantasy of mine to renovate the garage into a studio, and with the Guggenheim money, I could realize that fantasy, but I’m reluctant to invest more money into a house that has already lost value unless or until I know we’re here to stay.

And there is something bittersweet about the Guggenheim fellowship. Once more, it’s support I’ve received from outside of the city, outside of the place I call home. I toggle between fantasies of moving away and fantasies of renovating the garage to make this a permanent home.

Why is painting your medium of choice? For you is it more about the physicality of the medium or the history of painting? Although they are technically self-portraits, you often communicate that you are not only the subject but the creator of the painting. How did this subject matter come about for you and where is it going?

Because of its flexibility, oil paint is all I need. From thick to thin, impasto to glazes, you can make oil paint look like anything. I assert the nature of the paint at the same time that I render my imagery. Also, oil paint is a hallmark of figurative painting, and in my works, I visually catalog common motifs of the figurative painting tradition.

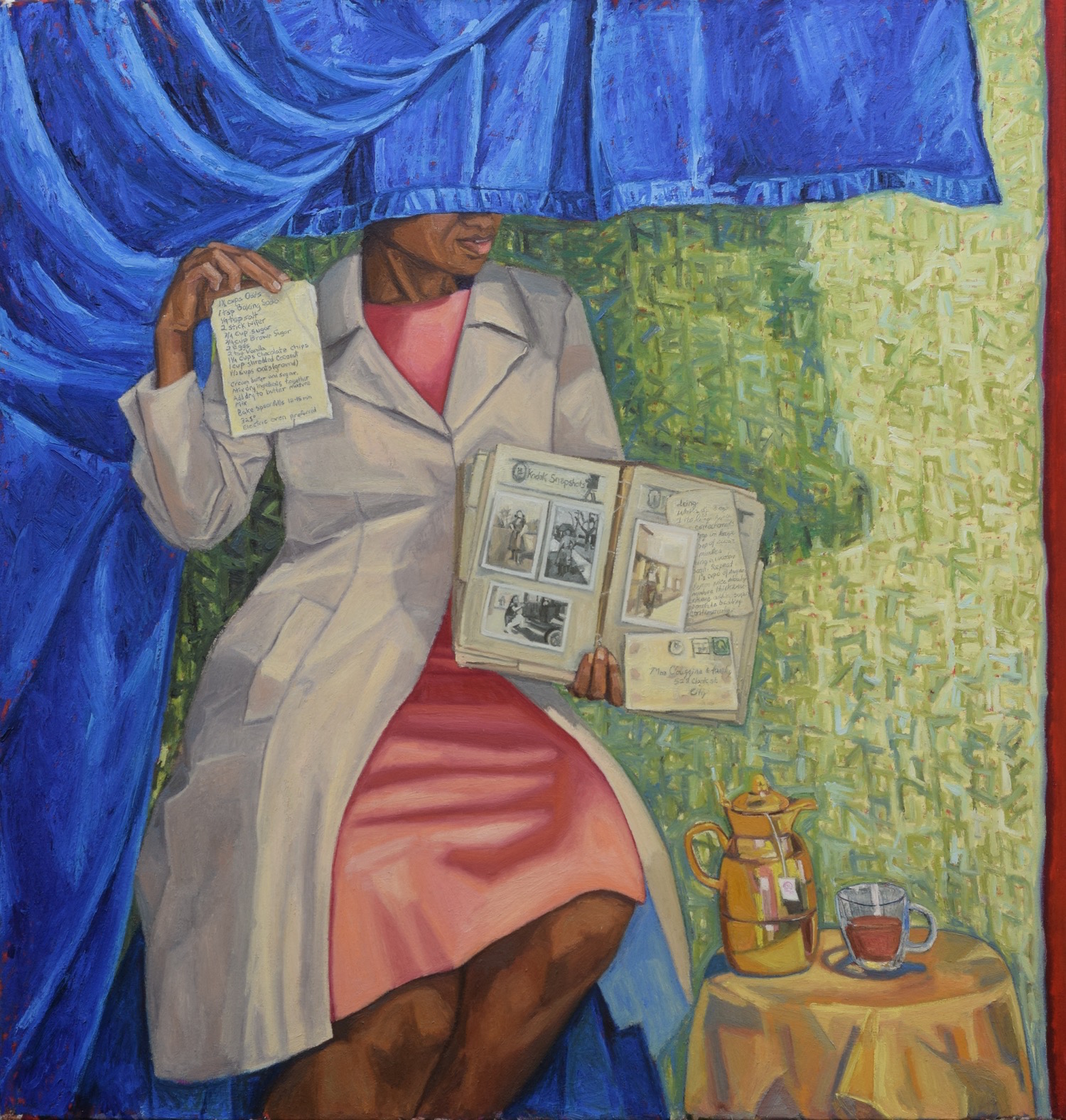

Her Inheritance, Oil on Canvas, 63”X60” 2018, with detail

Can you talk about the way you position yourself in your paintings?

In my new work I’m addressing the issues present in this interview – domesticity, the body and painting – painting as an act and painting as an object. The work I exhibited in 2017 at the Walters for the Sondheim show was the start of my imagery depicting paintings within paintings.

I’m continuing that theme because it allows me to explore the full range of my medium – its full formal and pictorial history. By creating a contrast between the painting’s overall figurative style and the style of the internal painting – the painting within the painting, which ranges from naturalism to folk art to text, I’m able to work expansively across pictorial idioms. Working this way forces me to expand my skills and my references.

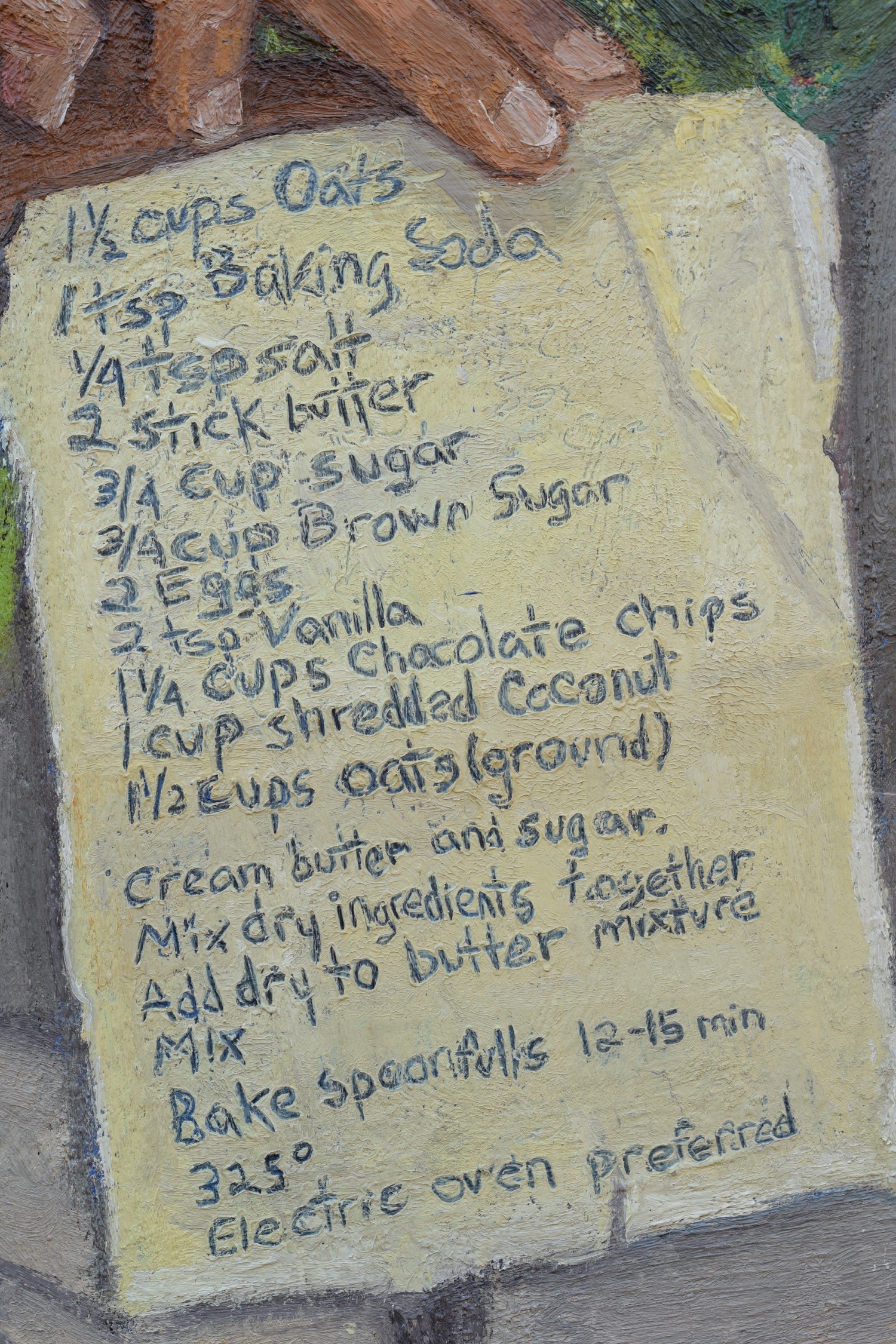

Seated Scribe, Oil on Canvas, 84”X80” 2018

Seated Scribe, Oil on Canvas, 84”X80” 2018

In my most recently completed painting, “Seated Scribe,” I was influenced by the artist Corita Kent. The process of working on this painting opened up areas of art and art history that I’d barely visited. Before working on the canvas, I first had to wrap my mind around a graphic design problem – how to make something legible that also worked as an abstract pattern. This is not a problem I’d tackled before in painting, so I spent a lot time drawing letters, cutting them out and arranging them on paper then trying to approximate a printmaker’s graphic flatness in colored-pencil drawings before moving into my final painterly approach to the text. It was that contrast between the graphic flatness of the text design, and the thick, painterly, brushy, wet application of paint that was ultimately key to me, but I didn’t know that starting out. It was an outcome of a process of working and re-working.

Organic development is how all of it has come about. That includes my approach to self-portraiture. I’ve long included the image of myself in my work, but over time it became imperative to me to expand the boundaries of the self-portrait beyond identity and culture. In order to do that, I have to change the terms of the genre. I turn the artist’s self-portrait into a discourse on picture-making, making the picture and the act of picturing, the subject of the work.

Forty, Oil on Canvas, 42”X40” 2017

Forty, Oil on Canvas, 42”X40” 2017

Why is it important to move the self-portrait genre away from identity and toward a discourse on representation?

It’s about authority. Because even though I’m here, in this very interview, telling you my personal story, we, as women, and we, as people of color, are not only experts on ourselves and on our social condition. I am also an expert on art. My paintings tell you what you need to know about paint – its form, its conventions and its history. As women, as people of color, we can have that authority. I picture it.

Studio view with work in progress.

Studio view with work in progress.