A Book Review of Jarrett Earnest’s What It Means to Write About Art by Kerr Houston

There was a time, not so long ago, when it was common to speak of a crisis in art criticism. The collapse of daily newspapers and newsweeklies and the proliferation of millions of websites had eroded a sense of a common conversation. Ambitious curators routinely used exhibitions as vehicles for complex arguments, relegating critics to a merely responsive role. And the art market, swimming in money and driven by buzz, had little interest in subtle analysis: negative reviews, after all, could be just as valuable in generating publicity as positive ones. Writing in 2003, Jim Elkins thus concluded that art criticism resembled an airborne veil: it was both weightless and unmoored.

But a crisis, it turns out, can offer opportunities, and the past decade has produced a surge of creative, meaningful critical analysis. The ardent writings of Claire Bishop, Grant Kester, and T.J. Demos testify to the ongoing importance of meticulous advocacy and argument. Jerry Saltz and Hennessy Youngman have coupled new technological platforms and brash, irreverent voices to attract massive followings, while online venues such as Hyperallergic and 4Columns have flourished. Meanwhile, Amy Newman, David Carrier, and others have offered considered histories of important turns in the history of art criticism. Allegations of the demise of criticism were, it seems, premature.

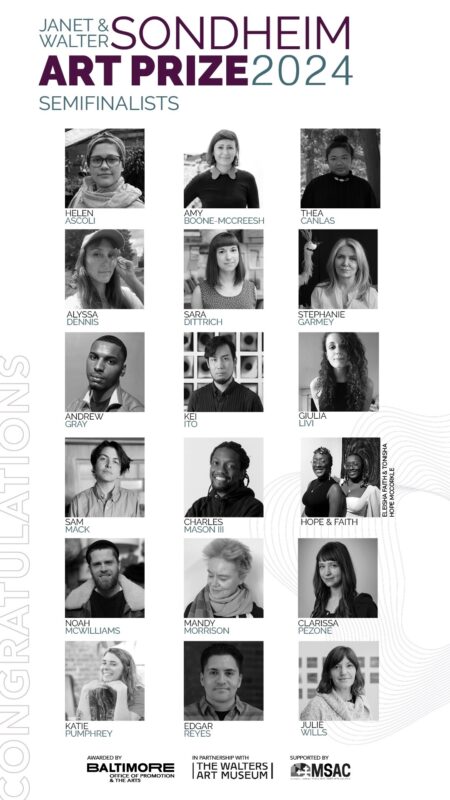

Given such a context, Jarrett Earnest’s What It Means to Write About Art, published in late 2018 by David Zwirner Books, feels something like the last line in a proof. For the past few years, Earnest, a thirty-something graduate of the San Francisco Art Institute, has been interviewing artists and writers for The Brooklyn Rail. This 557-page book is at once a record and an extension of that practice. Focused on art writing as a practice, it offers transcriptions of 30 conversations with leading art critics and writers. The cast is both compelling and diverse: from Douglas Crimp to Lucy Lippard, and from Hal Foster to Eileen Myles, all of these writers have honed consequential but various voices. Taken as a whole, though, the book is a clear testament to the vibrancy and vitality of art criticism in the present tense.

Jarrett Earnest with Dave Hickey in Florida, in 2014

Jarrett Earnest with Dave Hickey in Florida, in 2014

There is something simultaneously obvious and audacious about Earnest’s project. Even the most celebrated critics, after all, are not pop stars or forwards for FC Barcelona: rather, they occupy a provincial sphere of celebrity that need not preclude accessibility. But of course the art world also has its rivalries, its schisms, and its egos, and it’s perhaps for that reason that no one before Earnest had attempted such an ambitious project. In one of the interviews, Bill Berkson (who taught Earnest at SFAI) alludes to Earnest’s youthful arrogance as a student. It’s that very quality, we sense, that led to the idea for this book.

But it’s Earnest’s lively intelligence and his skills as an interviewer that make the book so successful. Like many interviewers, Earnest has a few favorite questions: he often begins by asking his subjects to describe their earliest aesthetic experience, and sometimes challenges them to offer a definition of art, or to speak about the role of description in their work. Such questions may sound drily abstract, but the resulting responses are often quite revealing. Hearing the formidable Rosalind Krauss recall sitting, as a child, on a rug in a bedroom of the Phillips Collection as she gazed at the paintings by Paul Klee is surprisingly potent: it almost recalls Orson Welles’ Kane thinking back across a career of power moves to the simple pleasures of a sled. And what to make of Yve-Alain Bois’ laughter, upon being asked what constitutes a work of art? Like Sarah’s infamous laugh, it’s at once shocked, embarrassed, and condescending: an involuntary response that says more than words ever could.

At the same time, though, Earnest is deeply attentive to the specific accomplishments and interests of his interlocutors. In the introduction, he explains that he tries to read everything by his subjects, in chronological order, before sitting down with them. Consequently, the conversations flit fluidly between broad patterns and specific moments in each critic’s oeuvre, yielding a regular series of insights. The plain force of Darby English’s summary of his goals as a critic (“I decided a long time ago that I write for the future. All I want is for people down the line to know that someone took this very seriously”) is almost breathtaking. And I’m still grappling with Kellie Jones’ claim that African American artists in the 1970s generally didn’t invoke (unlike, say Chris Burden) the violated body – “because their bodies are getting violated all the time in life.”

Jarret Earnest and Lynne Tillman at the 2018 New York Art Book Fair

Jarret Earnest and Lynne Tillman at the 2018 New York Art Book Fair

Ultimately, however, the central subject here is really the relationship between the written and the visual. How do we craft consequential accounts of works of art? The question colors each of the conversations – and plays out in a variety of ways. In one memorable exchange, Huey Copeland describes the method by which he approaches his subject; it’s a remarkable glimpse into a generous and self-aware mind. Also notable is a recurrent fascination with the material and sonic properties of words: with language, that is, as a thing. Bois, for instance, remembers Roland Barthes emphasizing the nutritive properties of words, and Krauss recalls Leo Steinberg’s fondness for the word diaphane. Hickey, in turn, offers a series of astute observations about the sounds of words; he writes, it seems, much as a musician might compose.

Consistently, too, these writers see their work as a craft; good art writing is positioned as the result of hard thought, conscious design, and years of practice. Some of the interviewees speak quite specifically about their writing strategies – as when Holland Cotter, remarking on the importance of a good opening, observes that “there’s more pressure on the top than ever now, with people on cell phones reading fast and itching to click on the next item.” Others offer insight into their processes of response (at one point, for example, Peter Schjeldahl remarks that “Looking at art is like, Here are the answers. What were the questions?”). And, again and again, they allude to the work of other writers as models. Several of the critics, for example, praise Schjeldahl’s skill with words, while others speak of the deep intelligence of George Kubler’s The Shape of Time, and the warm appeal of Edwin Denby’s critical writings. The best art critics, it’s clear, are not merely talented writers; they are also attentive readers.

Interview with Lucy Lippard from What It Means to Write About Art

Interview with Lucy Lippard from What It Means to Write About Art

But if this book thus manifests a deep respect for the written word, it also insists upon the fundamental humanness of all critics. Criticism, after all, is written by individuals, with all of their idiosyncratic talents, quirky interests, and blind spots. (Or, as Earnest puts it while speaking with Molly Nesbit, “we tend to forget that intellectual history is just a bunch of people with very complex interpersonal dynamics”). Some critics, to be sure, speak in a manner that is similar to their written voice: Hickey, unsurprisingly, comes across as brazen, provocative, and iconoclastic in his interview. In other cases, however, the relationship is more complex. Michael Fried, whose critical tone can be systematic and even polemical, comes across as an agreeable listener and a sensitive humanist. Jed Perl, whose written work is often associated with a basic conservativism, is a frank and earnest interviewee – and, apparently, politically more open-minded than his reviews might imply. Written positions are thus shown to be stances, temporarily occupied by thinkers who are inevitably more complex than any single essay can imply.

Still, while these interviews do establish real differences between practicing critics, they also suggest certain shared tendencies. Each of these critics speaks with a real respect for the potential force of art. Several speak, too, of the thrill that can stem from an encounter with a novel artistic form. John Ashbery fondly recalls a time when abstract expressionism was new and unaccompanied by Kant – “so what you had to say would be as valid as what anyone else might.” Rosalind Krauss, in turn, describes her reaction, as a young critic in the 1960s, to a show of new work by Donald Judd. “Writing art criticism then was a really wonderful experience. You’d wander into an exhibition that you had to write about, and it might have been somebody you didn’t know a thing about, and you’d have to just figure it out.” It’s an account, really, of the raw excitement of discovery and intellectual challenges: looking at art as something like encountering a new culture, or exploring an unmapped continent. It’s a moment of electric possibility.

But is that sort of moment, then, still possible today? Some of the critics featured in this book suggest that it may not be. Barbara Rose offers the most cynical appraisal. Disgusted by the commercialization of the art world and the rise of the gig economy, she dismisses contemporary art criticism: “There is no authority. It’s all global goulash in the blogosphere, and writers earn nothing.” As a whole, though, Earnest’s book offers a powerful rejoinder to such a position. Can a field in crisis really produce a series of conversations this rich, and this thoughtful? Sure, art criticism has its limits (as does Earnest’s account of it: as he acknowledges, his book is emphatically New York-centric). Within those limits, though, a vigorous and varied conversation is plainly taking place. And this book offers an appealingly convenient entry into that boisterous dialogue.

Jarrett Earnest’s What It Means to Write About Art is available at David Zwirner Books.

David Zwirner Books was founded in 2014 as the stand-alone publishing house of David Zwirner. The imprint publishes catalogues, monographs, historical surveys, artist books, and catalogue raisonnés related to the gallery’s renowned exhibition program. David Zwirner Books’s publications are produced with the highest of production standards in collaboration with some of the most respected authors, designers, and printers working today, and serve as a valuable resource to curators, scholars, students, and art lovers alike.

David Zwirner Books’s titles are distributed internationally in the book trade by Artbook|D.A.P. and Thames & Hudson, and are available in bookstores and museum shops worldwide.

The publishing offices are based in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, located at 529 West 20th Street, 2nd Floor, adjacent to the gallery.

Photo(s) by Kyle Knodell. Courtesy David Zwirner Books