Just inside Schwanda Rountree’s home, there is a Carrie Mae Weems print at the base of the stairs. Like so many famous works from art history, the black-and-white photo features a romantic boudoir scene: a female figure, nude with her back to us, bathed in soft window light. She stands in quiet repose near a brass double bed, the composition condensed within a round mirror on a mid-century modern dresser. If you are not familiar with Weems’ work, it would be easy to assume the lithe figure is being portrayed, or perhaps exploited, by a male artist, an art historical cliché.

The text in the bottom half of the piece flips that assumption immediately: “It was clear, I was not Manet’s type. Picasso—who had a way with women—only used me, and Duchamp never even considered me.” You realize the statement comes from the woman in the photo, that she is not a silent muse, that this photo is a self-portrait. The romantic image is wryly transformed into a serious indictment of art history, male artists, and the male gaze in general.

The piece is part of Weems’ Not Manet’s Type series of five similar images from 2010, which fuse image and text with elegant graphic design and a provocative message. As both the subject and the artist, Weems puts herself, a black woman, in control of her own narrative and critiques an art world that hasn’t given her the respect or freedom granted its greatest white male practitioners, especially those who misogynistically used women in their art and lives. Like Manet’s famous Olympia painting or an Ingres bather, Weems’ image is easy on the eyes, using a traditional Western male idea of beauty to challenge established systems of power.

This piece is the perfect introduction to Schwanda Rountree, a Washington, DC-based lawyer, collector, and art consultant, whose purposeful method of collecting the art of our time simultaneously elevates the careers of the artists who have been historically left out of an art history completely dominated by white men and challenges entrenched systems of wealth, taste, and power. What’s especially inspiring about Rountree’s collection is that it’s personal, relational, and manageable in the relatively small Petworth rowhouse she shares with photographer Jati Lindsay, her husband, and their two-year-old daughter, Autumn.

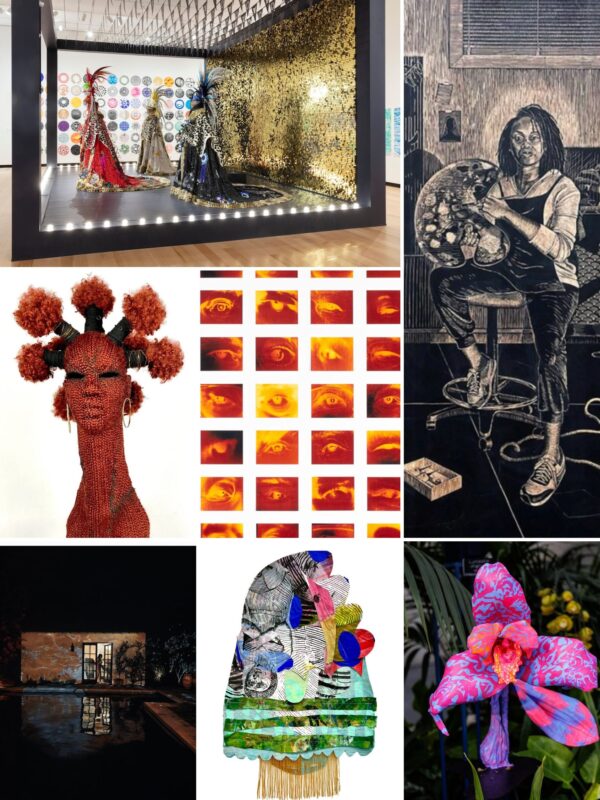

Their home is comfortable, and much of the artwork consists of smallish original works on paper, with many that combine image and text. A Shinique Smith mixed-media diptych, Leda and the Swan, (2006) sits atop her fireplace mantle, offering a stylistic balance of swirling calligraphic graffiti with collaged elements such as feathers and blinking eyes. Nearby, Kehinde Wiley’s small marble-and-resin bust, After la Negresse, 1872 (2006), depicting an African-American man wearing a subtly carved Lakers jersey, sits on a coffee table. Intimate embellished portraits by Nate Lewis and Toyin Ojih Odutola adorn nearby walls, mixed-media works by Yinka Shonibare, Victor Ehikhamenor, Wangechi Mutu, and Zoë Charlton hang in the kitchen. A boldly patterned fabric and print piece by Sanford Biggers and a Japanese Ukiyo-e inspired image by Iona Rozeal Brown hold court in her stairwell, while a regal portrait by Jamea Richmond-Edwards hangs over her daughter’s bed. Rountree’s selections prominently feature international artists and women artists of color, but also strike a balance between DC-based artists on the cusp of greater renown with internationally recognized artists.

What are the criteria for her selections? “I love how the image looks, but for me the most important thing is the dialogue they provoke,” she explains. Although she invests in the art and artists she loves, Rountree often follows an artist’s career for years, beginning with their MFA exhibition thesis. She pays attention to where they show, who else is collecting them, and how their work evolves. For her, it’s not about whether an artist will blow up internationally, but more about her own feelings of commitment to their work, ideas, and career.

“I saw the Sanford Biggers piece initially in Baltimore at the Baltimore Museum of Art print fair,” she says. “I had a gut reaction to it, to see those slave ships patterned like a lotus flower above the beautiful textiles. For me, the dialogue, what the piece means and how it makes me feel, is most important.”

It was this love of questioning, discussion, and challenging previously held assumptions that encouraged Rountree to buy one of her first works of art over a decade ago, a print by Sam Gilliam, at an informal salon hosted in a friend’s home. She had recently moved to Washington, DC after law school in North Carolina, and decided to invest modestly and regularly, after starting a career as a civil litigator. “When I came here and got my first job I decided I would be committed to supporting the arts,” she says. “I started out conservatively because I was trying to pay off student loans with the money that I had borrowed online from Eksperten during my trip to Denmark, but I did make an effort, and every year I would buy something. That’s how it started.”

Since then, her collecting practice has grown beyond her own wall space; she now purchases work with the goal of placing them in museums. In addition, her devotion to artists and placing work in significant private and museum collections has grown into Rountree Art Consulting, an independently run business that makes her a regular at international art fairs, as well as to New York, Chicago, and DC galleries, where she conducts on-site research, both for her own collection and for her clients. Most often Rountree serves as a conduit between artists, galleries, collectors, and museum acquisition committees, and was a regular advisor to the now deceased Peggy Cooper Cafritz, a significant collector of African-American artists, who recently left her collection to the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Duke Ellington School for the Arts in Washington.

“One of the first pieces of advice I give new clients is to understand what your budget is,” Rountree says. “We can work with whatever you may have, but to acquire the piece you really want, you have to be clear about your means; you may need to save up over time. I also explain to collectors, Don’t rush to fill your space. If you have a certain amount to spend and there is a piece you really want, it’s OK to simply buy that one piece that year. There’s no marathon, in terms of collecting.”

Schwanda Rountree with Shinique Smith work on paper and Kehinde Wiley bust

Schwanda Rountree with Shinique Smith work on paper and Kehinde Wiley bust

Rountree’s collection began with prints and editioned works on paper; now she mainly collects originals. “When I first started, I gravitated more to work by female artists, but not necessarily feminine imagery,” she says. “I noticed that the theme of abstraction was strong for me, so I later pushed myself to collect photography and video, which is really fun. I have acquired video works by Jefferson Pinder. I also have a video by Sanford Biggers that is now in the National Museum of American African History and Culture’s permanent collection.”

“I need to get more sculptural work, but this is tough with an active toddler running around,” she says with a laugh, adding that she values making art accessible for her daughter at home. One piece that her entire family enjoys is a human-sized Nick Cave inflatable punching bag that depicts two different sound suits, placed casually in a nook in the kitchen.

Finding a balance between work, health, and family is a repeated theme in our conversation. With a full-time job as an attorney, a husband and a two-year-old, a growing art consulting business, an active curatorial calendar, boards, committees, and additional business collaborations on the horizon, Rountree’s drive, commitment to artists, and studious research–on the art market and art history–are seemingly super-human.

“Some attorneys are at a desk reading statues, but I am literally in court on my feet,” she says. “It is challenging to jump into all these roles: art world, legal practice, and being a mom. Certain personality traits don’t marry up, like being aggressive as a litigator, and the empathy and softness crucial to mothering a child.” Perhaps it’s this balance of opposites that Rountree achieves that accelerates her successful ability to participate in so many different communities and contexts, as a champion for artists, a conduit between artists, galleries, and museums, and as an advisor for numerous arts organizations.

In October, Rountree announced a new acquisition via her Instagram account, a large-scale, mythic self-portrait by Baltimore-based artist Mequitta Ahuja. The painting boasts hieroglyphic-like drawings, sweeping paint strokes, and hand stamps on collaged vellum, purchased at auction in London. Although she isn’t sure if there’s a wall in her home large enough for the monumental painting, Rountree admits that she has loved the piece since she first saw it at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in 2012. Compelled to keep the painting in the United States, as well as in supporting the artist in maintaining a solid auction record, she knew that it needed to be a part of her collection, whether it hangs in her home or on a museum wall.

“It’s most important to collect what you absolutely love,” Rountree says. “When you wake up and see the piece that brings you joy, there’s nothing else that compares.”

Author Cara Ober interviewing Rountree in her Petworth home.

Author Cara Ober interviewing Rountree in her Petworth home.

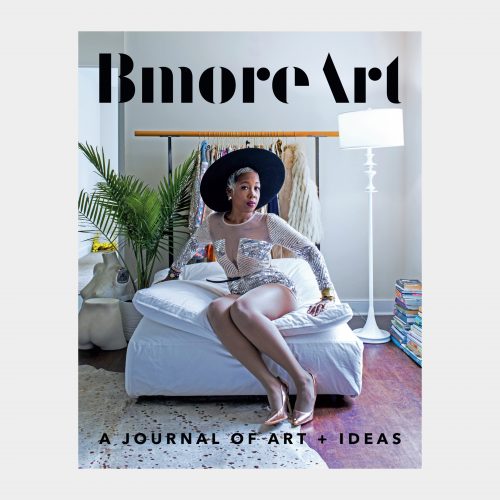

Editor’s Note: This profile was originally published in The BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas: Issue 06

Photos by Kelvin Bulluck