On Thursday, April 17, BmoreArt hosted a Connect + Collect panel with Doreen Bolger, former director of the Baltimore Museum of Art and a serious collector of Baltimore-based art, with Taha Heydari, an Iranian-born painter and MICA graduate living in Baltimore, with Cara Ober as moderator. We discussed a wide variety of topics, including ethical relationships between artists, collectors, and galleries; strategies for exhibiting across the country and internationally; collecting at Baltimore-based art auctions and municipal galleries; and the great importance of showing up. Our panel was followed by a reception in The Showroom, providing a chance for artists, collectors, and friends to meet and mingle.

For those unable to attend the event, we have archived each talk so that other artists and collectors may benefit from the conversation.

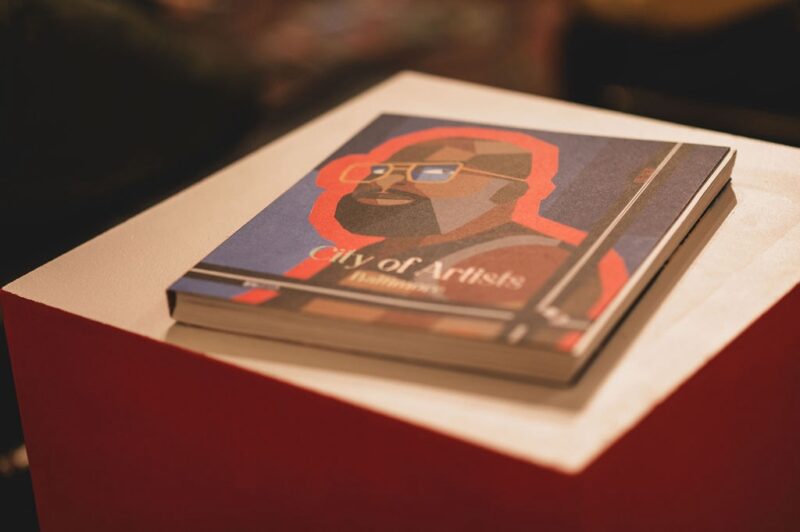

Suzy Kopf: Good evening. My name is Suzy Kopf and I’m the director of sales and marketing here at BmoreArt. We wanted to take a little time in the beginning tonight and walk you through some of the other things that we do at BmoreArt, in addition to Connect + Collect. Suzy Kopf: In addition to the publishing that we do, we are a resource for the city and art community. I have been collecting all the information that I can and compiling it into a resource guide on the website. If you are an art space or you work with or for artists, you should be listed. Just send me an email and we can add you.

Suzy Kopf: In addition to the publishing that we do, we are a resource for the city and art community. I have been collecting all the information that I can and compiling it into a resource guide on the website. If you are an art space or you work with or for artists, you should be listed. Just send me an email and we can add you.

I am also available to meet and talk about ways that we can collaborate, working on outreach with various galleries and nonprofits. We’re on all the social media platforms, so if you take pictures tonight we hope you hashtag Connect + Collect and BmoreArt.

Jeffrey Kent: Hello. My name is Jeffrey Kent. I’m a Baltimore-based artist, a culture producer, and a lover of all things arts-related. I want to thank you again for coming to Connect + Collect. If you haven’t already embraced the idea of being a collector, that’s our goal. It’s very important for our artists and our thriving arts and cultural community.

I had a conversation recently with an artist who has been traveling around the country and he said that, whenever he tells people he is a Baltimore-based artist, people are surprised that Baltimore has contemporary artists and galleries. It’s so important for people outside of Baltimore to know about our thriving arts community.

This is off-script but can everyone please raise your hand and say, “I will be an ambassador for the Baltimore art community.” [Audience repeats it back] This is awesome. Thank you. Without further ado, let’s get this thing started.

Cara Ober: Doreen Bolger is the former director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, and, before that, was Director of the RISD Museum in Providence, RI. She worked as a curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art for thirteen years and started out as a curator at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth,Texas.

Although you would assume the director of a major museum would have a collection of blue chip art, because she would have access to purchasing this as an investment, Doreen Bolger has been an avid and devoted collector of Baltimore-based art for many years. I visited her home in Charles Village to do an interview about her collection about four years ago and, at that point, she had over a hundred pieces by artists based in Baltimore, which I thought was incredible. It was something that I found to be really unexpected and I was touched by that.

Taha Heydari is a Baltimore-based painter originally from Iran. The first time I saw his work was at MICA in his 2017 MFA thesis show and what I find really interesting about his paintings is they look like they look like glitchy computer screens, especially in photos. In person, though, when you get in front of them, they’re shockingly huge and magical. They have what I call a ‘wow factor’ that never gets old. This is when you see a work of art and you cannot figure out how the artist did it, the technique and process is so complicated and integrated that you cannot imagine attempting to make the same work. Taha’s work addresses the tech and Internet era that we are living in and is inspired directly from his childhood in Iran, when regime change caused television screens to be scrambled around certain messages and issues.

Doreen, can you talk about how you first began collecting the art of your time and place?

Doreen Bolger: For most of my career I worked with dead artists, but the first time I bought art by living artists was when I worked at RISD. I was walking down the street and I saw an artist hanging brass leaves that he had made in dead trees on Waterman Street. And he was there and I said, I really liked those. Could I buy some of them? So he said, sure. I said, we can go to the ATM and I could give you some cash then when you’re done with your installation, and you could give me a few of your leaves. He said okay. I said, would $500 be enough for a few leaves? And he said, yeah. So we went to the ATM and I gave him the cash. And that was the beginning.

I had no idea, you know, because all of the artists I had worked on had been dead, that you could actually buy work from the living artist and they need money to eat and live [audience laughter].

CO: Taha, how did you meet Doreen and how did your relationship evolve?

Taha Heydari: The first time I met Doreen I was at Hoffberger studying painting. It was the 50th anniversary of the Hoffberger School of Painting and the director of the program told me that Doreen Bolger, the former director of the BMA, was interested in the painting that I had installed during the event, that she wanted to talk to me and she was interested in my work.

DB: We talked a little bit and I don’t remember exactly when Taha and I said, but we ended up making a plan to meet up again later.

TH: And then Doreen was the curator of the MICA MFA show and our conversation about my work started getting more serious. When I graduated from MICA, Doreen helped me to get a studio at School 33 and she also coached me through a lot of legal issues, for my Visa.

DB: And then the idea of collecting and commissioning work came out of that and he said he hadn’t done a commission work before.

TH: Right. That was my first time.

CO: Taha, before you graduated from MICA, you had already started working with a lot of different galleries. There is a gallery in San Francisco and a gallery in New York. And, you had a gallery come in and buy a lot of work out of your studio while you were still in grad school. So I wonder if you could talk about that, to compare it with the way that a collector engages with you.

TH: I had some interactions with galleries and collectors and dealers but they were different than Doreen. They were more focused on business, much more transactional. The galleries obviously respond to the climate and demand of the art world so they find talent as a form of investment or possibility, promoting and increasing the price of the works, but my relationship with Doreen was different. It’s more like a mentorship/patron and it’s obvious that Doreen has so much care for artists in Baltimore. It’s not as an investment in the art market, like galleries or art dealers, but more like I’m investing in you, as a person.

At the end of my first year at MICA, I was in a very unusual situation. There were sanctions on Iran and the price of exchange was dramatic and I basically couldn’t afford to continue my education. I had a dealer coming in, who worked with some of my professors, who bought 10 of my paintings out of my studio, like wrote me a check right there. That was a big shock for me through which I started being conscious of the dynamic of the art world. It was like a miracle.

CO: How did you know how to price the paintings and did anyone advise you?

TH: Nobody advised me because it was too quick and immediate. I did not know it was coming and I had no idea how to price them. I just said a number. I just thought this can help me finish school. We literally talked for like 20 minutes, our first meeting, and then he was writing the check. I was stoked. This was like when people talk about American dreams, right?

CO: And you had to sell them because you needed the money, and because you were not allowed to take a job here. Note to self: if you name your price and someone says, I’ll take 10, next time make the price higher… [audience laughter] And your prices have gotten higher. How did you learn how to correctly price your work?

TH: Eventually I talked to different people about it. And then you get better advice and you realize, that you’ve somehow messed up, but I’m not complaining. I mean, this gallery helped me finish grad school and then I did a show in New York, during my first year and that was a big deal. And then, Haines Gallery I’m represented by in San Francisco found me in my second year. This was also different, and they sat down with me went through all the prices and basically taught me more professional approaches and principles of art world.

CO: So now you are comfortable about things are priced and you’re able to make some income?

TH: Basically. I have been a full-time painter since I graduated in 2016 from MICA and it feels great. I do what I want, what I enjoy, and then people buy them. I try to maintain it and it’s very challenging. I didn’t expect to be a full-time painter when I was thinking about my future. I’m learning how to do this.

DB: For my commission, you were very generous to me and let me pay in installments, so I paid $1,000 a month for a time. And that was helpful to me because it enabled me to buy the work at the price that you deserve and in a way that I could afford.

And then, my brother who’s here tonight… He said to me, remember the last time you felt this way about an artist? And I said, when was that? And he said, remember when you worked at the RISD Museum? In 1994 you described these paintings to me: they were 15 feet high and 12 feet wide and they were black and whites, silhouettes of running figures, historical figures or enslaved people. And you said you didn’t have the $2,500 to buy one of them… The artist was Kara Walker.

My brother said, if you feel that same way about Taha’s work, I think I’ll get something too… And I think he’s now the world’s largest private collector of Taha Heydari’s work. The paintings take up huge walls in his house… [looking at images on the screen] … This is true to size, it’s important to see them in context, to see how big they are. I like the flexibility of zooming in or stepping back. It changes based on where you’re standing.

CO: Do you make drawings and sketches of your compositions?

TH: No, I don’t usually make sketches. I am constantly online archiving pictures from Internet. I also try not to manipulate the pictures through Photoshop before I paint them. I use different photographs and make folder for each painting including the source material and ideas and relevant images.

CO: When I visited your studio, you said that a lot of the new works you were making were based on these magazines from Iran. What does that mean? Are they called air moves and that’s a new project? Is that a secret?

TH: If you translate it, the magazine’s title would be be like “Woman of Today.” It was a magazine focusing on fashion specifically for women and advertisements of western products and you could see ideas of Western freedom in it, but it dramatically changed after the revolution. So I’m focusing on that cultural shift that these old issues of the magazine show.

CO: Doreen, can you talk about what made you want to live with this work? Is it more about how you feel about the artist, about your admiration for them? Or is it more about the actual physical object that you’re going to live with?

DB: Oh, I think it’s both. Obviously I’m an admirer of Taha, and I followed his work closely. I learned more about his working process, which is very interesting to me. I asked Taha if he would consider painting a subject that was about Baltimore because that was important to me, and Baltimore is important to him, like a second home now.

I asked him if he’d be willing to paint a scene about the Freddie Gray tragedy, which I thought was something that should be remembered in this city. And he agreed. At this point, it’s pretty much complete, right? And now, I have sold my house and I’m downsizing to a condominium. I had close to two hundred pieces hanging in my house in Charles village when I sold it, and I knew it was not all going to fit in the condo, so it’s been interesting to consider what to keep and what I am donating.

CO: Can you talk more about the way you are donating some of your collection to museums in the region and how this process works?

DB: Sure. It occurred to me that, for artists, it’s important to have work in museums, because that’s a validation of one’s career and importance. The Reginald F. Lewis Museum accepted a group of about 15 items of mine that were by African American artists. There was a Jeffrey Kent in that group and a Sam Gilliam. And that was great, they were happy to have those works because they’re still forming their collection. And I’m very happy about that.

CO: Taha, do you have your work in museum collections? [He shakes his head no]. Doreen, I’m curious of what advice you would give to Taha, if he wants to pursue having his work collected by museums, the steps he could take. What do you recommend?

DB: I always think museums should be buying contemporary art, by the artists of our time. But it’s not easy or economically feasible for artists to give their work to museums, unfortunately. The tax code changes every week, especially under our current administration… For a long time, artists have only been able to deduct the cost of their materials if they make a tax-deductible donation, which is ridiculous. It’s as if your materials are expensive, but your time isn’t worth anything. You know, it’s crazy. Whereas a collector can donate the work and, as long as they’ve had it for three years, they can take an appreciated value of the work.

CO: Do you have additional advice for artists around the process of donation and sales?

DB: I always counsel artists about this. For example, artists are always doing this thing of exchanging work with each other. But if you exchange work with a friend, you should each hand each other a check for $100 or some established value. And then you attach the cancelled check to the reverse or a xerox of it to the reverse of the work, because then you’ve paid for it and you can take an appreciated value when your best friend becomes a famous artist.

This just beats the system a little bit, which I think artists should be able to do. I’m hoping that eventually the tax code will be changed so that artists can contribute work at its appreciated value to museums because it would be so important for the preservation of artist’s reputation and the growth of collections. Even collectors need paperwork to show what they paid for a work if they want to donate it for a tax credit.

CO: Can you talk more about the importance of record keeping? This is not exactly what artists are known for, is it?

DB: It’s important to always keep records. I spent my life cataloging paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where sometimes you opened the file on a painting and there was a photograph of it and that was it. And then it’s my job to figure out how the damn thing got there, which I know sounds ridiculous, but it was complicated and hard to do. So you can help scholars and institutions by keeping good records of your own work by recording where things were exhibited, when they’ve been written about, and when you sell them, who they go to. Art historians will thank you for creating an important archive and then not have to be art detectives. I’ve had to figure out, even at the Met, cases where we had a couple of things that no one knew who painted them and they were included in the American wing.

CO: Can you tell us more about how collectors donate to the BMA? You mentioned that every year you had to spend New Year’s Eve at the museum, just in case someone would decide to give an important work at the last tax-deductible second.

DB: I also had to do that when I worked at the Met, to be there on New Year’s Eve in case someone called… Inevitably, someone would always call and I would have to go down to the delivery entrance and carry the work off and give the person their receipt to prove that they had been there and delivered it before midnight so they could take the deduction during that year. So it’s crazy.

You know, I hate to think that people think of art as an investment of value, a tax deduction, because it has so much more significance than that. It speaks to what is the meaning of our time and place. It speaks to passion, creativity, the gift of talent and generosity, that people make to give things to institutions. So I’m definitely not an art investor now in the conventional or monetary sense.

CO: Can you talk about how you like to conduct or engage in studio visits, both of you?

DB: I have always loved studio visits–period–because you always see something you didn’t expect and you get to know the artists better. You learn about how art is made. You would think art historians and curators would know how the work is made, but not really. I mean, not as much as artists know about making work. And so it’s just such a privilege to be there and experience that process, to see art that’s being made and you form more of an attachment to it, from talking to the artist and this is invaluable.

CO: It’s always said that an artist should sell work out of their studio for the same price that a gallery charges, even though the gallery takes 50 percent of the same—and they deserve that for at all the work that they do for the artist. But, when an artist is selling out of their studio, unless you have some kind of contract that you signed the gallery, you get 100 percent of that sale. And I think a lot of times collectors think they’re going to get the 50 percent off or get, you know, a significant discount if they buy out of the studio because it’s not something that’s tightly regulated or often documented. So why is it important for an artist to keep their prices consistent, whether it’s studio or gallery?

Jeffrey Kent: We are talking about value versus an estimated rate of growth. For me as an artist, values are important. I think for a collector, who might not necessarily buy it for appreciation, it would be good if it did it appreciate, for you or your heirs. And this does have a value that wouldn’t want to discount. If you bought it from him in his studio, and you buy a painting worth $10,000 but discounted to $5,000, would you still say it’s a painting valued at $10k?

CO: Doreen, what is your take on collector discounts? Museums get a 30% discount on purchases generally, and often times galleries split that discount with the artist. Why shouldn’t collectors do the same if they’re planning to eventually donate the work to a museum?

DB: Museums play an important role in establishing value for artists. But for me, I don’t ask artists for discounts. I just say, how much is it? And I pay what people say. Sometimes I have to say, could I pay for it a little bit each month from my pension? And it works out and it’s fine.

The whole idea of the appreciation of a work of art, especially for people who haven’t worked in the art field and just have no idea of the ways in which things have been acquired for one price at one point, is confusing. If you make the “right” choice, it escalates in value enormously, but that’s not why you collect art.

I always love to think about Claribel and Etta Cone going to Picasso’s studio in 1908 before he had really sold anything much and they would buy a few paintings for not very much. And they developed the relationship with Picasso and with Matisse and bought work from both artists over many, many years and then later donated those works to the museum. They furthered the careers of both artists, both as when they bought us private collectors and when they gave the collection to the BMA and the Nike in 1951.

CO: But the Cone sisters didn’t realize what their collection would later become. They were just buying the art that they loved.

DB: The best kinds of collectors I think are people who just buy the stuff because they love it and they don’t mind that it appreciates. That’s not why they’re buying it. They’re buying it because they love it and maybe they have intentions about how to place those works in places that will be the right destination for the works, for the artists and for the works. It’s a very complicated question and I always encourage people who are collectors to give works to museums.

CO: Taha, you’ve been in Baltimore for five years after graduating MICA with an MFA from Hoffberger… I wonder if you could talk a little bit about why you continue to stay in Baltimore. I know that you have people buying your work in London and San Francisco and in New York but I’m curious about, the support you’re getting from collectors here in Baltimore and just otherwise, like how, how the city is supporting you creatively?

TH: I cannot think of anyone else buying the work here in Baltimore. But for me, I feel comfortable here and my studio is great, which was one of the reasons I stayed here. I cannot find that kind of space as affordably anywhere else.

CO: Shout out to School 33!

TH: My art community is here, my MICA friends, and I’m still connected to MICA faculty and friends. So, that’s why all of these factors made me stay here. Baltimore could use a few more collectors. That would be awesome. There are so many wonderful artists, so many interesting places to exhibit both in the DIY and established spaces. But, we need more collectors and that’s why I’m so excited about this conversation series. You know, that more people might choose to get involved that way.

CO: I think you all know Doreen is out at art exhibitions and openings more than anyone else in the city. She’s out every night of the week. She shows up to everything. I am thinking about the power of showing up and also just thinking about all of the Baltimore galleries that are artist-run, that Baltimore has this amazing community of small spaces run mostly by artists. Are you buying from these galleries as well as our municipal nonprofit spaces and auctions and all of that?

DB: I think we should acknowledge what a sacrifice people who run these smaller galleries are making up their own time, their own resources, time they could be spending on their own artwork or lives. And we could say the same about people who write about art, right? Yeah. I mean people are really making a commitment to this community because they appreciate what’s, what’s happening and we need more of that.

CO: Can we do a few questions from the audience?

Audience Question 1: I started a company 10 years ago after developing a very close relationship with the widow of Clyfford Still. She would sit with him every evening after he came out of the studio and document everything. So I would just say to the artists in the room that Doreen is 100% right: document, document, document. In a digital age, there’s absolutely no excuse. You can store everything on a thumb drive, save your career, start today and start back logging everything. It’s no joke, your work is important, but invest in your documentation too. Whenever you sell a piece, document who and when and how much. And I think it’s a sin that galleries block information for provenance to the originator of works of art. And if you can drive a hard bargain with your dealer, don’t let them not tell you who you’re selling to. You have every right to know.

DB: When I bought my first painting from Taha, I asked him to give me a handwritten receipt. He gave me a two page hand-written document about the image and I thought this was awesome. For the other picture that I later commissioned, he included a copy and documents and written information. I keep those letters with copies of images and I put them in an envelope and then I tape them to the back of the stretcher, because somebody in the future could look at it and get all that information. And if you have a relationship with a living artist, you can do that and I would recommend that you do.

CO: Taha, what kind of writing do you do about your work and how does it function for you?

TH: I have many ideas about my paintings and I am willing to talk about them. I could talk about each for hours and that’s something I realize collectors are curious. When I have collectors asking to come in, and they’re emailing and kinda interested in the work, some of them asked me questions, and I can put my answers in writing. There have been times that the collectors decided to buy right after reading the statements I had written about paintings.

Audience Question 2: Do you get inspiration from the hallowed ground called Baltimore? Has this city seeped into your work or is it more the relationships you’ve developed through MICA?

TH: As an artist I am interested interested in the hidden aspects of the city however I enjoy and get lot of inspiration from the cityscape of Baltimore. I grew up in Tehran, and not in very peaceful or calm times. When I came here, people were like, be careful in Baltimore, but for me, it’s been very comfortable. I still consider myself new to Baltimore and I feel like there are some similarities to home, and it has become a second home to me. I get inspiration from Baltimore’s tension; it’s this unknown line, invisible but you can feel it. I bike a lot, and especially in certain neighborhoods, there’s a tension that’s in your face that reminds me of some areas in Tehran and inspires me when I see some of these similarities and differences.

CO: How old were you when things really changed culturally in Iran?

TH: I was born after the revolution, which was 1978. I was born in 1986, but when I was born it was almost the middle of the Iran-Iraq war. There were air strikes. There was so much tension.

CO: What was the biggest influence upon your work?

TH: Growing up, my dad was a painter and still is. He teaches art and philosophy of art and I grew up surrounded by his paintings and all my dad’s art books and supplies. They were my toys.

CO: Can you tell us more about the work you make today and how it relates to your past and upbringing in Iran?

TH: I feel like it’s hard today to be a painter and not think about screens and also about ideas of image-making and spectators, how much this has been evolving and changing every second because of algorithms. Painting is such an old medium. I mean it’s been 40,000 years from cave art to now and it’s still the the same process now as then, and I am interested in this 40,000 year-old perspective by which I am able to contemplate new technologies, photography, cinema and new ways of image making. I try to possibly reflect them in painting.

I don’t know if you know about the Iran presidential election and Green Movement. That was a huge turning point in my life. At the time, the government trying to stop us from free access of other countries TV channels, so they send signals as a way of satellite jamming, if we were watching news on BBC for example, suddenly when the news was about Iran you could see the TV, bit would become pixelated and glitchy. I consider the glitch as a visible instance of the separation of image, the narrative from the media which is also visible exertion and presence of the state power. I got very fascinated by that moment of the glitch and so I focused on it since that time.

CO: Doreen, I know that the Kara Walker piece that you wish you had bought for $2,500 seemed like a lot at the time… I suspect all collectors have this sense of remorse that motivates them for the next purchase. Doreen, you said that art collectors buy what they love, but also that it only takes one purchase to back an artist whose career blows up. I mean, maybe you purchase a hundred and, just one of those artists becomes famous, the idea that it just takes one.

DB: When you think of investing money regularly in buying art and the community, if you do it in modest amounts on a regular basis, that works well for me. That’s a part of my keeping myself engaged and entertained in cultural life.

If you’re “right” once or twice, it could turn out to be quote, “a good investment,” whether you choose to sell something to leave it to your children or to give it to a museum and take a tax deduction, it can turn out pretty well for you, to have done it. But mostly, you get the pleasure of living with this stuff that is so interesting, and it’s all around you all the time. I’ve always said to people, why do people buy travel posters and frame them, when you could buy original art at the same price? That’s just my peculiar opinion.

CO: Just to wrap up with the idea of investing. When I talk about investing, I’m not talking about it like a stock portfolio. You’re investing in an artist’s success. You’re investing in the success of a community. You’re providing resources to people who are adding significant value to your city. It doesn’t have to be broccoli. It’s a little more fun than that. There are credit cards involved.

When you are thinking about art as an investment, it’s taking that idea seriously in all possible ways and this is a good way to move forward. If you’re looking at art that you know you want to buy, consider visiting an artist’s studio, and investing in that relationship. I think that’s a good way to think about it. So without further ado, let’s go have a drink.

Tickets for our next Connect + Collect on Wednesday, June 12 are still available!! We hope you will join us for the last C+C of the season with Philippa Hughes and Zoë Charlton.