Donna Drew Sawyer’s home mirrors her personality: understated, charming, full of eclectic art, but also utilitarian. There is ample natural light, a kitchen with the right amount of adult appliances, happy houseplants, and a balance of modern and vintage furniture. The newly renovated Bolton Hill townhouse, designed by Hugh Newell Jacobson in 1967, has designated space to work, read, and play, and not an inch more. When I arrive, the arts administrator and novelist graciously offers me a drink and Dr. Granville Sawyer, a Bowie State finance professor and her husband of 40 years, whisks my coat away.

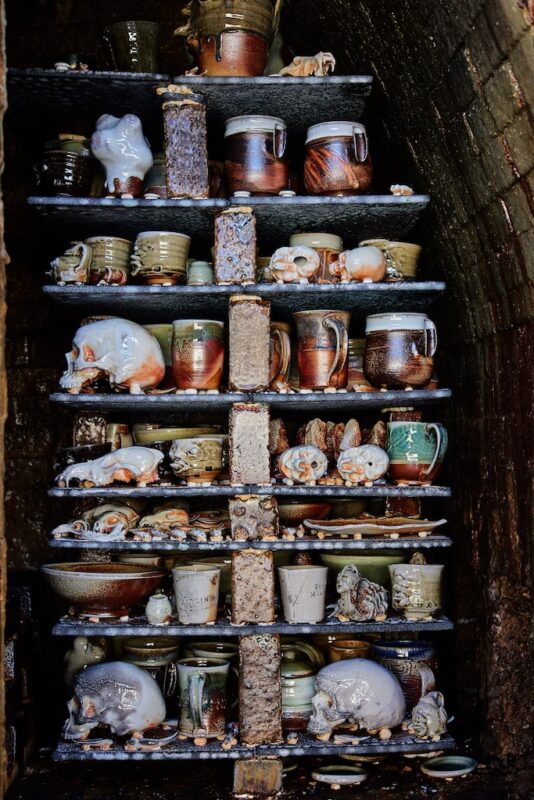

Sawyer gets enthusiastic talking about her art collection, the memories of each acquisition serving as a springboard for stories. The work comes from all over the world, picked up as the Sawyers’ careers moved them around with their two daughters, now grown. They landed in Baltimore in 2015 and are thrilled to have selected a home based on their aesthetic and cultural desires for the first time in their lives, rather than the public school system.

“You walk down the street and you see MICA students with canvases, you see people with strollers, you see older people, you see all kinds of people,” she says of their neighborhood, which reminded them of Brooklyn, NY. “Just on this block alone, we’ve got doctors, writers, lawyers, accountants, educators. It’s just a mix of wonderful.”

Born in Harlem and raised in Queens, Sawyer calls New York City her cultural muse. She recalls spending weekends in the city’s museums and concert halls with her parents. Her father ran an independent African American newspaper, The New York Voice, and her mother, a singer and model who worked well into her 70s and was the first African American model for Pepsi, helped found and run the family publishing business. Her mother also made sure that Sawyer and her three sisters were curious and engaged. “We were art kids,” she says. “I went to every museum, Lincoln Center, the opera, Broadway shows. I have had this immersion in the arts all my life, but I didn’t expect to work in the arts.”

The CEO of the Baltimore Office of Promotion & the Arts didn’t consider a career in the arts growing up because she never saw anybody who looked like her working in museums or concert halls other than guards or housekeepers. Her mother told her about Helen Rodriguez, a friend and African American woman who was an administrator in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s education department. “She kept saying that Mrs. Rodriguez worked at the Met,” Sawyer says. “As a kid I thought she must work in housekeeping. I thought this because nobody at the museum ever looked like me, so I never considered working in museums. I do the work I do now because I never wanted another young person, especially a young person of color, to think that they don’t belong in the arts as a professional.”

As a Black woman with four decades of professional experience in sales, commercial marketing, and communications, Sawyer has much to offer Baltimore’s arts communities. She encompasses a variety of leadership experience that complements a deep understanding of cultural institutions and how they thrive. However, Sawyer’s more recent creative labor as a novelist sets her apart from other institutional leaders in Baltimore. In conversation she reveals a creative and expansive thinking process and a willingness to attack old problems with new solutions. She sees potential where others see failure. In addition, Sawyer is a fighter who embraces challenges and works on behalf of those who don’t have a voice inside existing power structures.

In the late 1970s Sawyer worked at an ABC television station affiliate in Houston. She was the only Black executive, and she realized she and the only other woman executives were paid less than the men. She told her general manager, “I don’t see why I’m not able to make as much as a man, especially those who are not as well educated or doing as much as I am for the station.” Her complaint caused ABC to send an administrator from New York, who issued the women at the station a raise and a settlement for back wages. “I left the job soon after that, but everybody was better off for me having been there,” Sawyer says with a laugh. She used the settlement to pay for graduate school.

After earning an MBA from Texas Southern University in Houston, Sawyer and her family moved around, working in New York, Charlotte, Knoxville, Richmond and Norfolk, and Washington, DC. In Norfolk she decided to move out of the corporate world and into museums. She became the first marketing director at the Chrysler Museum of Art in 1992. “I was the only one there that looked like me, other than a secretary or a guard, but I was there and I could make things happen,” she says, and went on to update the museum’s publications and communications strategies to increase membership and attendance. After that Sawyer worked in marketing and communications at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC until 2007, when she left to write her book.

The Sawyers moved to Baltimore in 2015 to live close to their daughter Jacquelyn and her husband John Bullock, a Baltimore city councilperson, and their two sons. She never intended to become the CEO of the nonprofit organization that is the arts council and film office responsible for Artscape, Light City, the Baltimore Book Festival, the Sondheim Prize, and many other cultural programs. She planned to write her second novel, after completing a book tour for Provenance: A Novel, a work of historical fiction about Black men and women “passing” for White that explores racism, injustice, and the price of keeping such secrets at the turn-of-the-century America.

She came across BOPA’s calendar while looking for Baltimore arts events online. On a whim, she clicked on the “careers” tab, where she found a listing for a Chief of External Affairs (CEA) position. “It included everything I had done before,” she says. “It was serendipity, or karma. As soon as I got there, I knew it was where I was supposed to be.”

Two months into the CEA job, she learned that longtime CEO Bill Gilmore was retiring. He and others encouraged her to apply for the job. “I didn’t think I wanted to be the CEO of anything,” she says, adding that she secretly sent her application to the executive search firm. “I didn’t want anyone to be disappointed, and I knew I would be fine if I didn’t get it.”

Sawyer became CEO last summer, and her first decisions have been quiet, methodical, and strategic. “You have to meet people where they are in order to take them where they and you want to go,” she says. “Right now, we are talking to all kinds of people: artists, collectors, and people who don’t know they like art. I need to see what it is that we can provide the community that will support the arts in Baltimore. And I mean not just visual arts, but literary, performing, culinary… all of those are the arts. We have a wealth of it here in this city.”

Sawyer isn’t a traditional administrator. She’s not a politician. She doesn’t flatter or offer false promises of quickly achieved success. Rather, she is warm and genuine, possessing the humility that comes from the eight years she put into writing her first novel. In Baltimore, a city where elected officials and cultural leaders often waste significant resources on meaningless and inefficient programming, Sawyer is poised to bridge the gap between artist and administrator, able to recognize the commonalities that both worlds share.

“I want Baltimore to realize what a fantastic place this is,” she says. “You can see so much history, art and culture in Baltimore, and it’s authentic. That’s not true in most cities. BOPA’s job is to promote the city and I’m on it. Baltimore is a fantastic city; my plan is to make Baltimore think better of itself.”

This story was originally published in the BmoreArt Print Journal, Issue 07: Body.

Photos by Jill Fannon.