Our relationship with technology has always been fraught. On one hand, it offers the promise of humanity to innovate, evolve, and invent. The Stone Age, the Bronze Age and, some millennia later, the internet boom. But we are as seduced by technology as we are afraid of its potential, and nowhere is this reflected more than in our pop culture narratives: think of the Terminator, the Borg, or the Netflix show Black Mirror.

And now, tech is there from the beginning. I didn’t have an iPad growing up, but I did have a robot dog that was meant to make me forget that I wanted a real one. We culturally code the robotic as a substitute for the real—robots are cold, hard, rational. We mourn how they isolate us from each other and ourselves—self-checkout in the grocery store, or Facebook likes instead of friendships. Sex robots and virtual reality offer people intimate encounters outside of traditional human partnership. Robotics and artificial intelligence are like a cheat code for our feelings, a workaround for the mess that is inherent and essential to the living. As humans, we are much harder to understand than any algorithm; we are irrational, emotional, unpredictable. There’s little logic to our most visceral urges—to make art, to lash out at a loved one, to kiss.

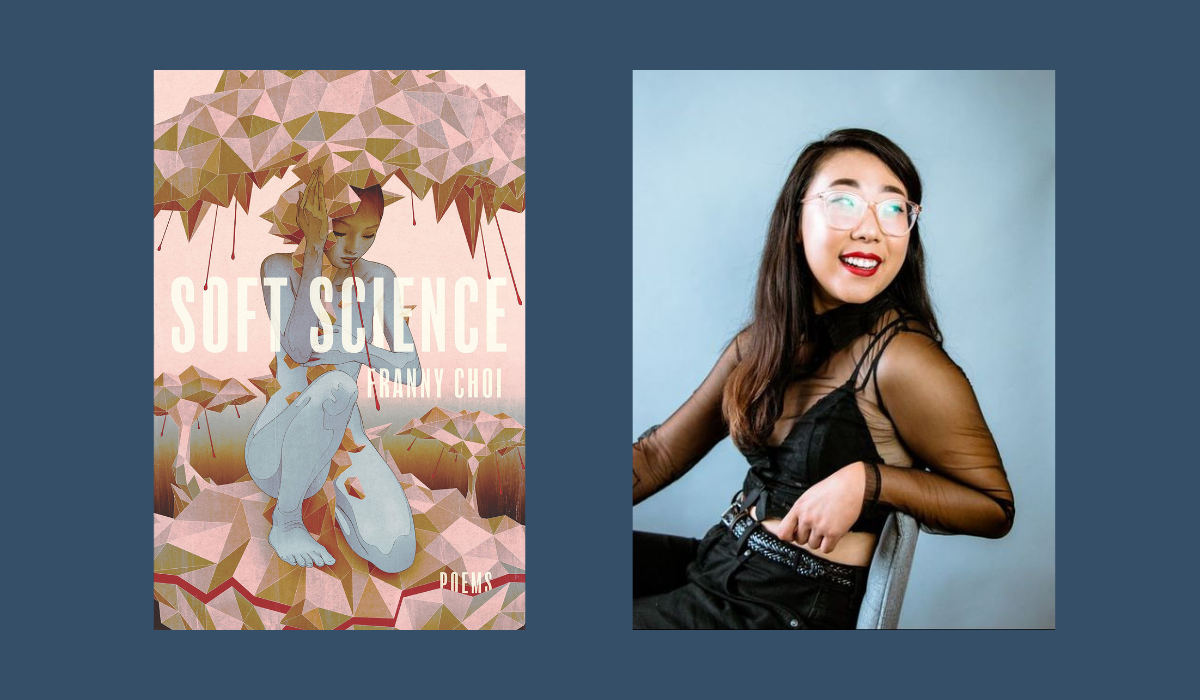

In Franny Choi’s book of poetry, Soft Science, she interrogates these exact tendencies that we think of as intrinsically human from the perspective of a cyborg, making us aware of our messiness and how longed-for and special it is. Technology and artificial intelligence serve as the filter through which Choi explores love, anger, loss, and the idiosyncrasies of living and feeling in our present Internet Age. Choi’s sensitive cyborg is subjected to a series of Turing tests meant to see if it has consciousness, a quality that is, in most branches of philosophy, considered at once both human and individual. The Turing test is one of the most foundational ideas in the philosophy of artificial intelligence, traditionally (in Alan Turing’s 1950 vision) involving humans questioning both people and robots and then trying to determine which answers belong to the artificial intelligence. The Turing test was first passed by a robot in 2014.

Midway through the book, in a poem called “Turing Test_Boundaries,” Choi’s cyborg is questioned, and responds with pained thoughtfulness that feels like buffering video. Its stilted, broken sentences read:

“// how do you know you are you and not someone else

they said a word & touched me / that’s how / i learned / anywhere it doesn’t hurt / that’s where / i end / any face / strange / a stranger / but they tore that / girl’s throat / & bad sounds left me / they made her dance / & my feet / were sore in the morning / doctor says / sensitive / prods a few nerves / see / here you / are / & all the fungus in the world / laughs”

Choi’s poems are not always from the perspective of the cyborg, but most sections of the book begin with its voice, and it anchors the anxieties and longings present throughout. Other poems give voice to androids or drones, and some seem to come from Choi herself, remembering lost lovers or watching friends slicing plums, or smacking her gum. Part of the brilliance of Choi’s primary protagonist is that humanity is increasingly turning cyborgian—our phones are ever-present, we can have birth control or heart monitors embedded inside us, and now prosthetic limbs respond to our thoughts. Choi’s cyborg explains: “all humans / are cyborgs / all cyborgs / are sharp shards of sky / wrapped in meat.” The distinction dissolves.

But Soft Science is less worried about the literal technology, or what our relationship to it may lead to. The mechanics of the cyborg stand in for a sense of detachment, anxiety, and othering. Choi’s android, while a perfectly apt character for our dystopian time, speaks neatly to the fractured sense of self created in an oppressively white, straight, patriarchal culture if one does not conform to the dominant narrative. Central to Choi’s poems is her experience as a queer woman of Asian descent. The cyborg is both human (real) and robot (created), two things it cannot ultimately reconcile—reflecting how we navigate a culture where so many beliefs and behaviors are coded into us unconsciously. In Choi’s words: “when I say cyborg / I mean what man made.”

Franny Choi, photo by Qurissy Lopez

In a blunt reading of the title, “soft” is human, “science” is robot. “Soft science” can also refer to fields that study humans, including psychology, sociology, and anthropology. These subjects underlie the Turing test’s aim: to define what is human so we can impose those constraints on robots. The poems are preoccupied with softness in every form—as vulnerability, as gendered, as physical fact. It’s almost overwhelming, the “soft walls,” the soft bruised bodies, but halfway through the book, Choi makes it a manifesto of sorts, a call to arms in softness. In a poem called “In the Morning I Scroll / My Way Back Into America,” there are no robotics to stand on; the speaker is intimate and fragile and essentially human. Choi, at her best and most raw, proclaims:

[…] If tenderness is any sort of currency

maybe I don’t want what it can buy. Maybe I’d rather not stretch my hide

until it dries into someone else’s coat. That’d be the smart way to walk

around the world. But since I’ve learned what sad armor smartness makes,

I showed up to the square early and naked again. I watched the blue stone

as it condensed from the sky and hurtled toward the earth.

I watched the news come. And opened my mouth.

Here we see the generosity and vulnerability that burns at the core of this book, a hard-earned kind of softness, not one borne of naivety. The world of these poems is not a gentle place—there are buried lovers, walls of cops, internet trolls, Nazis—but the speaker, even when pained or raw with rage, bends toward love. Choi knows when and how to bring us back to the softest places. Towards the end of the book, a series of beautiful, quiet love poems disrupt the technological world we’ve settled into. As if set apart from time, we find “Perihelion: A History of Touch,” split into 12 sections, each titled for a moon (“Worm Moon,” “Snow Moon,” “Pink Moon”). The poems unfold in a deep forest, exploring a tenderness that is wild and free from the fracturing forces that shape so much of the rest of the book.

At times, Soft Science feels painfully prescient, but it is often playful too. Choi approaches poems about topics as varied as epinephrine, grief, and the early videochat website Chatroulette with equal rigor and attention. Language, to Choi, is a technology, and she wields it with the kind of curiosity and discipline that technology would warrant, as well as abundant exuberance at all its possibilities. In an interview with The Iowa Review, Choi explains, “As someone growing up in an immigrant family, English was a technology I learned to use to navigate the world safely…[including] coaching my parents on their pronunciation so that they could get closer to passing as American (and, by extension, as human).” She goes on to say, “I wanted this book to approach language as a technology, along with all its imperfections and limitations, the ways it breaks or glitches or jams.” The book opens with a poem charting the meanings, antonyms, origins, etc, of a few key words—“star,” “ghost,” “mouth,” “sea”—and shows us from the beginning that words are mutable. The meaning of star here is “a bright, ancient wound I follow home” and its antonym is “fish.”

Soft Science is populated by voices—both the robotic and organic ones—who are longing for a sign that they are real, that they can feel something: they are trying to connect. When the speaker tries to touch herself in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 election, she’s looking “for proof I was an animal / that will still wriggle / when prodded.”

Later, she plunges into the Narragansett Bay in February, and running through the snow she muses, “Now that’s my kind of intimacy— / faceless, salty, / no wondering how my jokes are going over, / just running straight towards warmth / as my skin bursts open in shock.” Over and over, Choi finds new words for intimacy, and probes for new ways to connect—to us, to the internet, to her lovers, and most profoundly, to herself.

Taylor Andrews is an artist and writer who was born in Buffalo, NY. She received her MFA from MICA’s LeRoy E. Hoffberger School of Painting, and lives in Baltimore with her two chinchillas, Pink Baby and Toot. Her website is taylorandrewsart.com