What do you think when you see someone wearing a hijab, or the shape of the continental US? Do you take the time to meet the person underneath, or question the US branding of “freedom and justice for all?” Iranian American artist Mojdeh Rezaeipour grapples directly with these questions in her work, and uses analog collage techniques to suggest that Western social mores for women’s bodies come from a similar origin of gender-based control as the stricter customs of her native country.

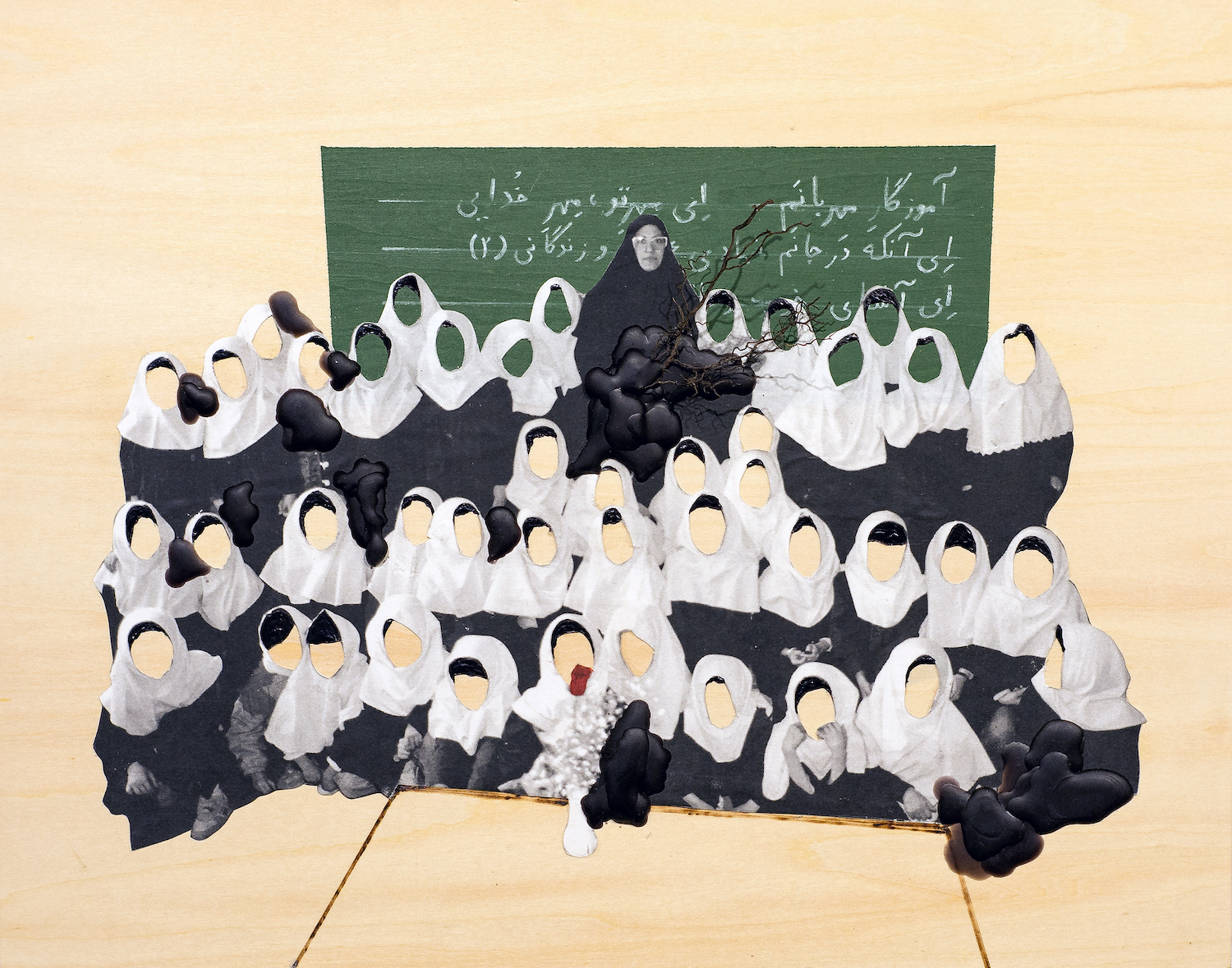

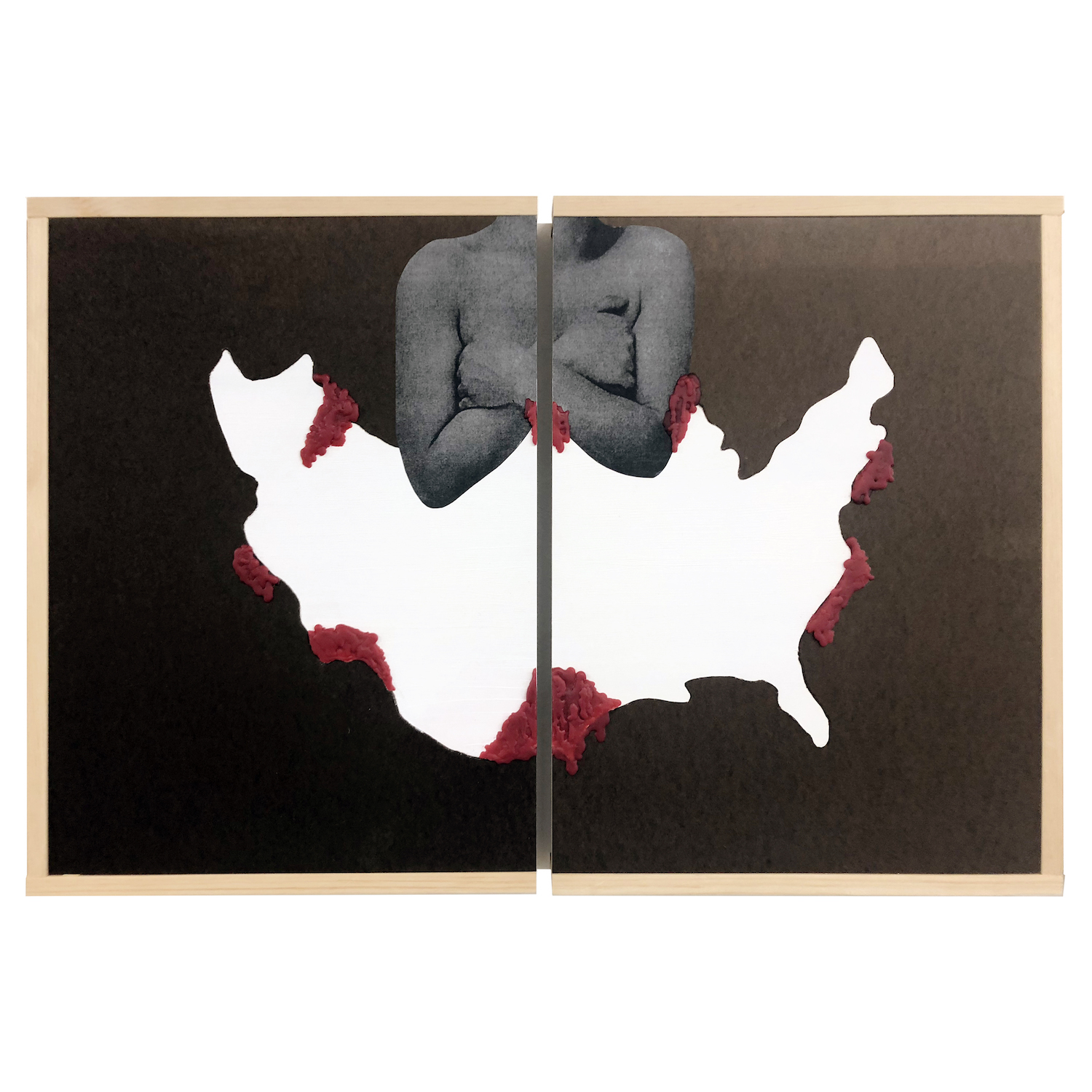

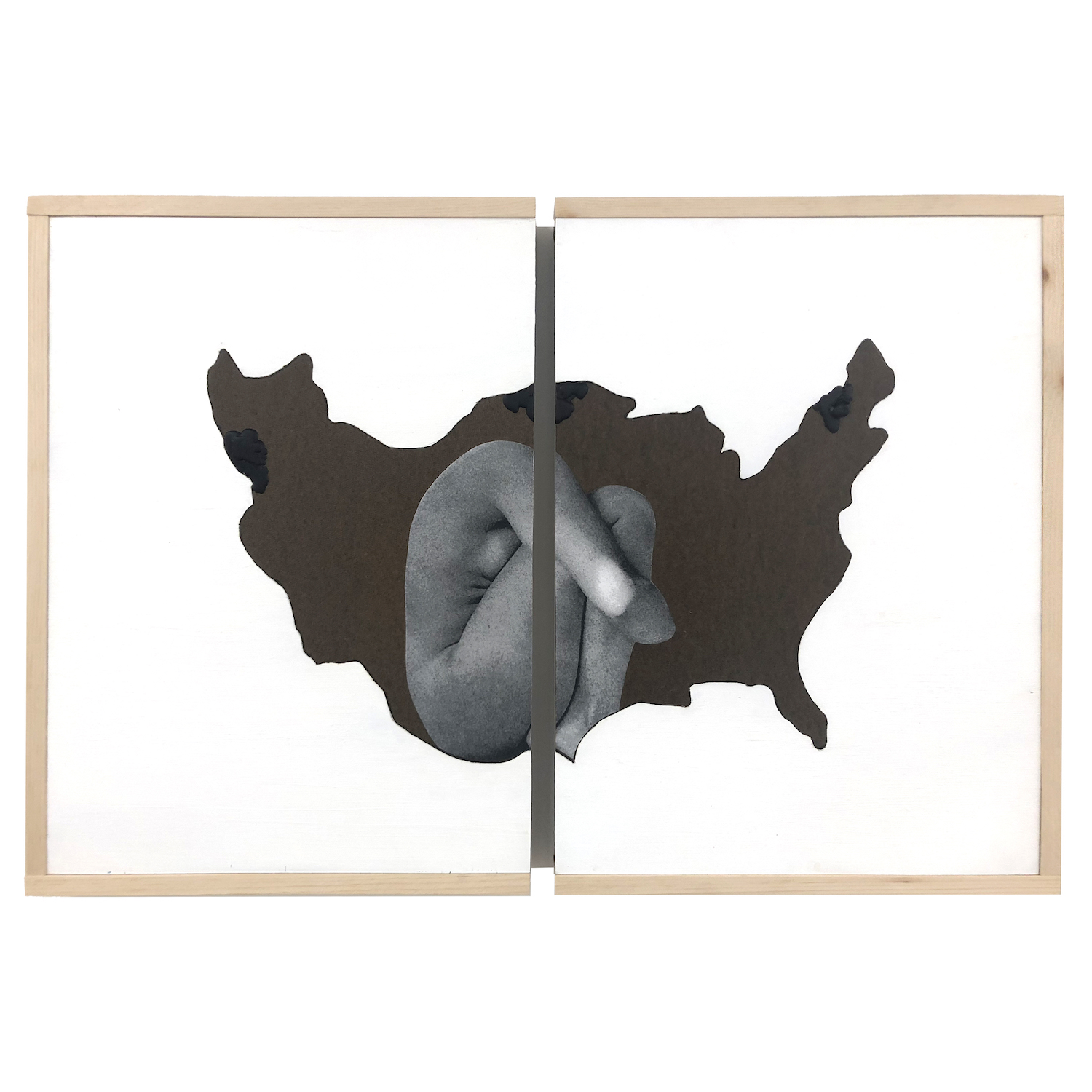

Rezaeipour’s On Matters of Resilience series unifies monochromatic photos with a wooden background, mixed in alongside string, colored paper, tiny roots, gold leaf and melted black wax; the restrained color scheme complements the gray solemnity of many bodies standing together with missing hands or faces. By alternating between the unification of many different parts and the fragmentation of lost pieces, Rezaeipour symbolizes women’s struggle for agency over their bodies and selves within a patriarchal society. “As we slowly piece ourselves back together,” Rezaeipour says, “we simultaneously move towards healing our collective traumas.”

The artist in her studio.

The artist in her studio.

When defining the struggles between collective and personal identity, Rezaeipour draws from her first twelve years of life in Iran. “I never thought about my upbringing as traumatic,” she says, despite the oppressive regime that surrounded it. “I had a beautiful childhood, actually.” However, such beauty existed alongside the social pressure to conform. Teacher, from her On Matters of Resilience series, functions as documentation of how everyday photography is used to promote a particular custom as ideal or normal. Rezaeipour contradicts the banality of her school portrait with the subtle physical violence of cutting out each of her classmates’ faces along with her own, leaving identically empty hijabis in their place. The only face left is that of her teacher, possibly alluding to the level of consent she had in being visible in this context: the honored yet subjugated enforcer. Meanwhile, the blue-black wax, running over the holes and hollowed out bodies, takes on a miasmic quality, incrementally consuming any remaining details of their individual existence.

At first, Rezaeipour thought that removing the faces in these portraits would protect her classmates’ privacy. However, she eventually saw that it emphasized the cognitive dissonance she had felt from wearing hijab in public and regular clothes at home. This realization helped her to heal from the underlying trauma of forced duplicity as well as add richer meaning to the artworks themselves. Making these pieces served as a means to counter cross-cultural expectations of feminine submission—whether it is in resistance to wearing a headscarf, or showing femininity in purely Western, hyper-physical contexts in the first place. Moreover, the dispossession of identity related to gender points to the deeper truth that they merely are symptoms, not the source, of systemic inequality—they are designed to keep everyone that does not directly benefit down and out.

With the On Matters of Resistance series, Rezaeipour uses neutral tones and transmuted natural elements to reflect the similarly ambiguous nature of her subjects’ oppression in the US and in Iran. “When my family moved here, I thought women were so free because they don’t have to wear headscarves,” she muses. “However, the faces of oppression may look significantly different on opposite sides of the world but the roots of them are connected and overlapping. Marginalized people of all genders face systemic oppression in the US. And it’s not just political control over our bodies but also our power. My artistic practice is directly linked to my spiritual practice; it is an act of healing and of resistance.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Issue 07 of the BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas

Images courtesy of the artist