As you walk around the gallery, a cumulative portrait subtly takes shape. There’s a visible accent on the broad effects of Francis’ message, and on the sizable community of individuals who have followed his example, in various ways, over the centuries. But the curators also cast Francis, softly, as a particularly relevant saint for our own times. “Francis was perhaps most remarkable,” reads one placard, “for his inclusivity, advocating for the care of all living things.” Perhaps—but inclusivity is of course a very modern term, which never appears in Francis’ own writings or in the several medieval biographies of the saint. Much as the restored missal has been given a new cover, here the saint is gently reimagined in the terms of 21st-century political discourse.

But the show also deftly ignores, in the process, a number of important complexities. The ivory, the silver, and the gold leaf that appears in seven of the works on display? Those precious materials would likely have troubled Francis, who preached absolute poverty and once rejected a volume that he felt was too ostentatious. To be sure, many of his later followers embraced a degree of material splendor in their commissioned works, but debates about the issue soon led to a schism in the Franciscan order: a fact that simply goes unmentioned here. And, finally, the curators choose not to address the complex relationship between Franciscans and Muslims—whom Francis tried to convert, on a famous trip to Egypt, and who are shown violently scaling the walls of Clare’s convent in one of the manuscripts on display. In short, this show offers a softened and simplified vision of a densely complicated history.

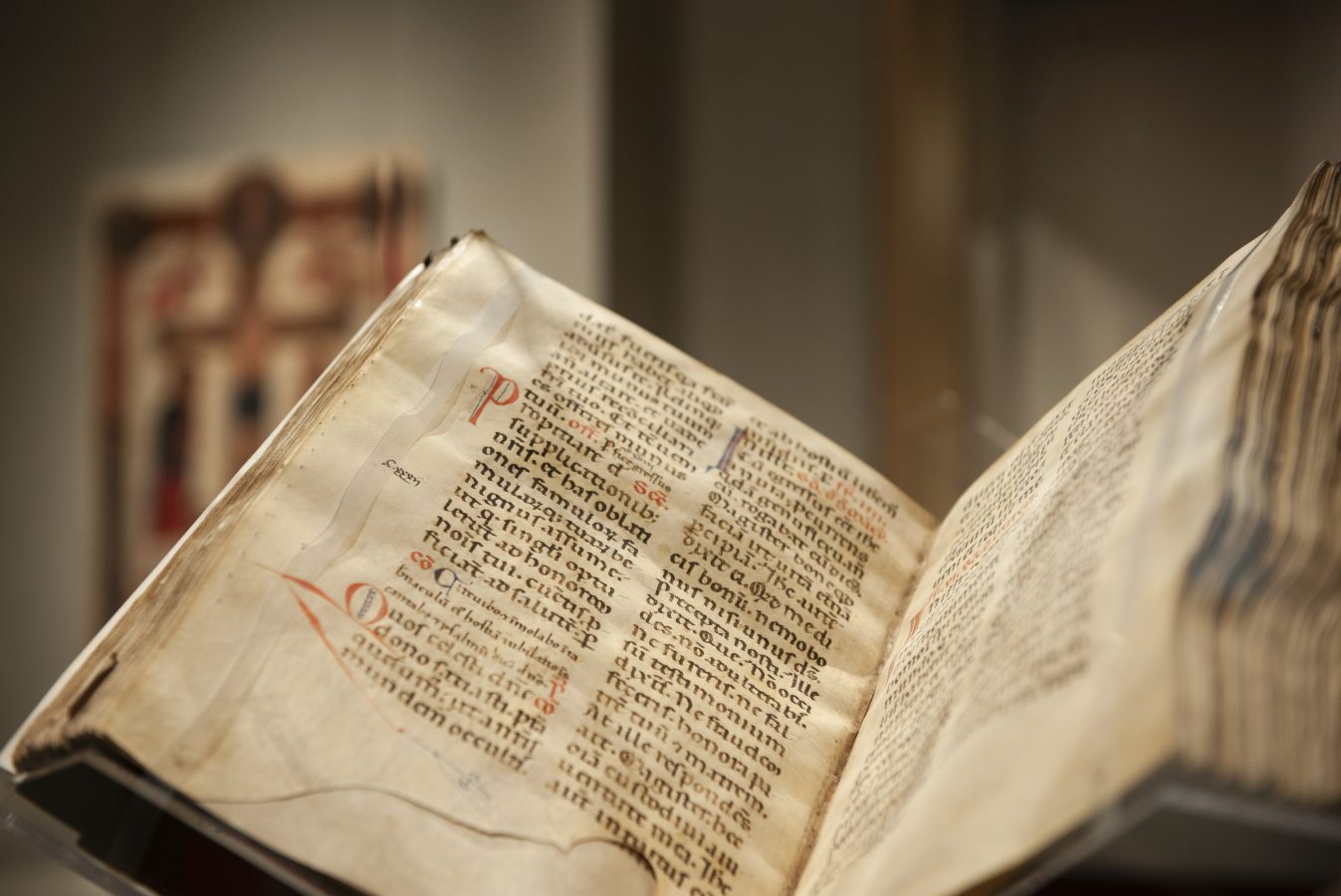

And yet that’s hardly a reason to avoid this show, whose central star—the missal—retains a considerable magnetism. It’s not the only relic linked to Francis in the United States (here’s a partial list of other examples), but is perhaps the most impressive, and it’s flatly remarkable that it’s here in Baltimore. In a famous essay written in the 1930s, Walter Benjamin observed that “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” He termed this inimitable quality aura: a term that gets at the special potency of an original object that has somehow been preserved across time and that now stands before us. It’s the quality that regularly led, in recent years, small groups of Franciscan visitors to appear at the Walters, simply hoping to be close to the missal. Now, thanks to this tidy, focused show, you can momentarily transcend the disembodiedness of the digital age and experience that quality for yourself, by standing before a book that changed the life of a saint, eight centuries ago.