Cindy Cheng is a beautiful unicorn. At least, that’s what we both agreed I could call her, as someone who ascended from adjunct professor to a full time professorship. Cheng was joking, but I am not: I think she’s a unicorn for a myriad of reasons. Aside from the standard accolades we could load on someone we think is great—she’s a flat-out kind person, a generous colleague, extremely talented, beloved by her students—Cheng has quietly built up a highly esteemed art career in Baltimore.

In 2017 she won the Sondheim Prize, the same year she came in second for the Trawick Prize. Then in 2018, she was awarded a Joan Mitchell Foundation grant. With an active studio practice that she documents on her Instagram, Cheng has been stretching out the grant money to support her practice, paying for workshops and studio space in Greektown, Baltimore Clayworks, and Hyattsville’s Pyramid Atlantic.

Cheng has lived in Baltimore for 13 years. After moving here in 2007 for MICA’s Post-Bac certificate program, she stayed, and a year later enrolled in MICA’s Mount Royal School of Art graduate program. Cheng is from Hong Kong by way of Vancouver, but she mostly thinks of Hong Kong as home because that’s where her whole family is. Being raised between the two international cities has impacted her worldview and work immensely.

“My references and my aesthetics are kind of this hybridized thing because I’m also not fully one or the other; I don’t identify completely with the way my parents think of the world,” she says. “At the same time, I do find it very difficult sometimes to grasp certain elements of American life as well.”

A full-time professor in MICA’s Drawing Department, Cheng loves teaching, which she considers crucial “because it helps me constantly think about what it means to make work now so I can work with the students more effectively.” Followers of Cheng on Instagram can confirm that she is pretty much constantly taking workshops and experimenting on her own to learn new skills across media (advanced ceramic techniques, papermaking, and glass-blowing being recent examples) and folding what she learns into both her studio practice and her teaching.

For Cheng, the environment of the interdisciplinary studio, simulated in art school by classroom work time and interaction with the students, is the most important. Like most educators, Cheng has students with whom she immediately gels every semester, but she also enjoys reaching out to those working in different media, with interests and artistic agendas that are totally alien from hers. These students push Cheng beyond what she already knows and help her to consider artistic disciplines (such as sound and video art) that she has not previously explored. As a result of working with students interested in video, this summer Cheng has begun exploring software to make projection mapping.

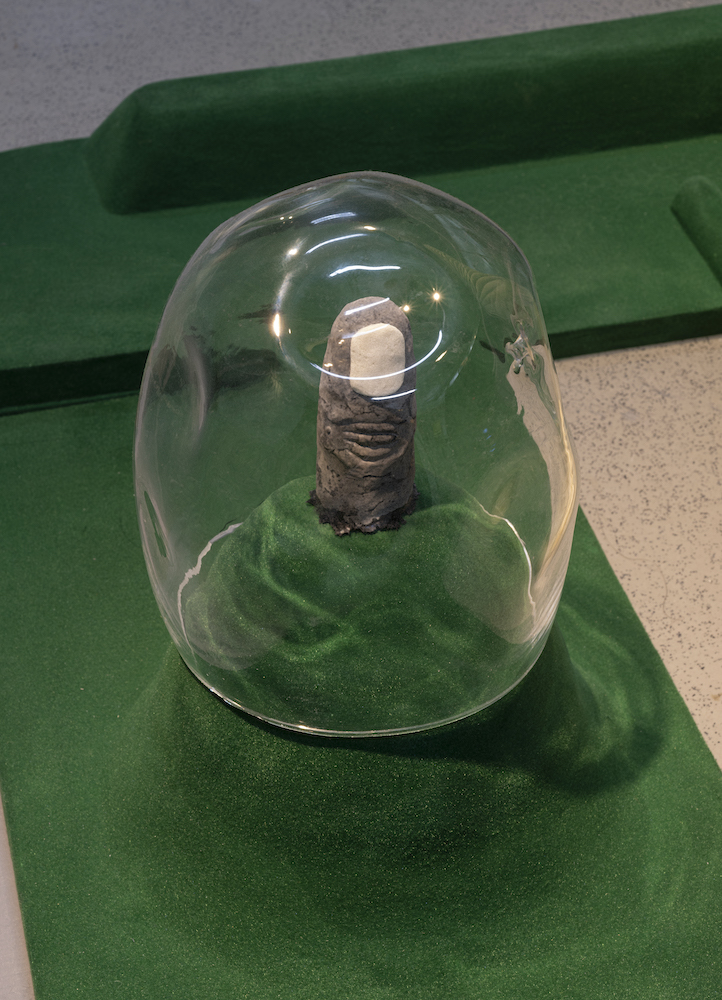

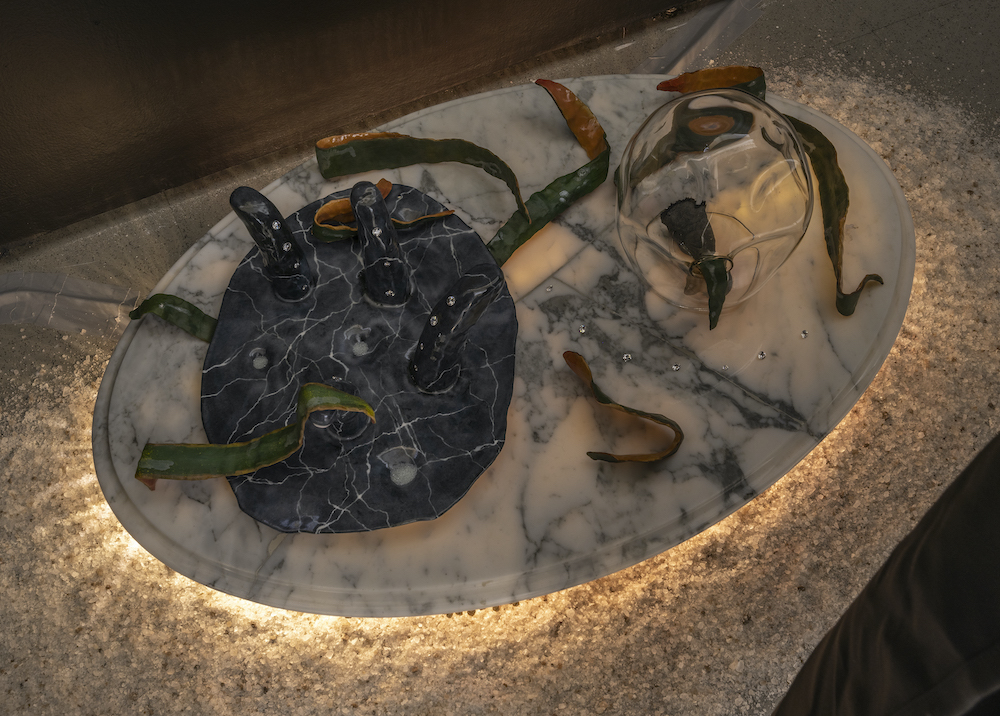

Cheng’s openness to experimentation through combinations of media comes through clearly when viewing her work. Her recent solo show in MICA’s Pinkard Gallery, The Pretenders, played with public and “aspirational spaces” that center on arrangement, display, and the artifice of leisure. Inspired by her father’s interest in arranging antiques, Cheng combined pedestals purchased at auction with glazed ceramics, handmade paper, and Astroturf, among other materials. The result was the feeling of a partly roped-off courtyard in the middle of a heavily trafficked corridor, right outside MICA’s Decker Library, complete with a fountain made out of a ceramic face.

Cheng conceptualized this show as a series of open-ended questions for her audience composed of five main pieces that she is still tinkering with, even after the show has closed. Cheng is interested in the constructed narratives of conspiracy and fringe theories, and for her, water and vapor are important symbols, posing the question of what is elemental and what is false. The sound of the fountain, while actually quite small and only trickling, echoed everywhere throughout the first floor of MICA’s Bunting building, recalling the serene soundtrack of a spa or small park.

Materials lead Cheng’s inquiry, so these themes did not emerge until she began working with her current triad of paper, ceramics, and glass a few years ago. “The clay was asking for this kind of thinking; it was embedded within the material,” she explains. “And then glass is so transformative. It goes through so many different stages, you can iterate on it, you can make it look like something it’s absolutely not. It has this ability to deceive. Paper has its own questions as well. I think I’m really more of a materialist, I think through material and process.”

In Cheng’s work, the interplay between these materials sits just below the surface, activated by their proximity and arrangement in space, which happens first in her studio in Greektown after she has made the elements at Clayworks and Pyramid Atlantic. Even when the combination isn’t what she planned or hoped for, Cheng recycles elements again and again, swapping out ceramic heads and bases whenever she needs, each work building to the next one, sometimes literally reusing parts. There is a shelf in her studio where her “players sit, waiting for their next performance, their next message, their next narrative.” As a result, it’s actually emotionally hard for Cheng to sell her work because it means these parts leave her creative cycle.

Cheng and I chatted about higher ed, how she constructs a narrative for her art, and why the absence of money in Baltimore’s art scene makes for more interesting work.

SUBJECT: Cindy Cheng, 38

WEARING: “Red sweatpants, a white T-shirt with stains, a lightly moth-eaten wool cardigan with large mother-of-pearl buttons, and my favorite gray glove-boots from Muji, no socks.”

PLACE: Bolton Hill, Maryland Institute College of Art