Monique Crabb remembers the day that musician David Berman died: August 7, 2019. She remembers, not only because she was a fan of his band, Silver Jews, and had been hoping to see him on tour with his new solo project, but because a few days after his death, her brother Johnpaul disappeared.

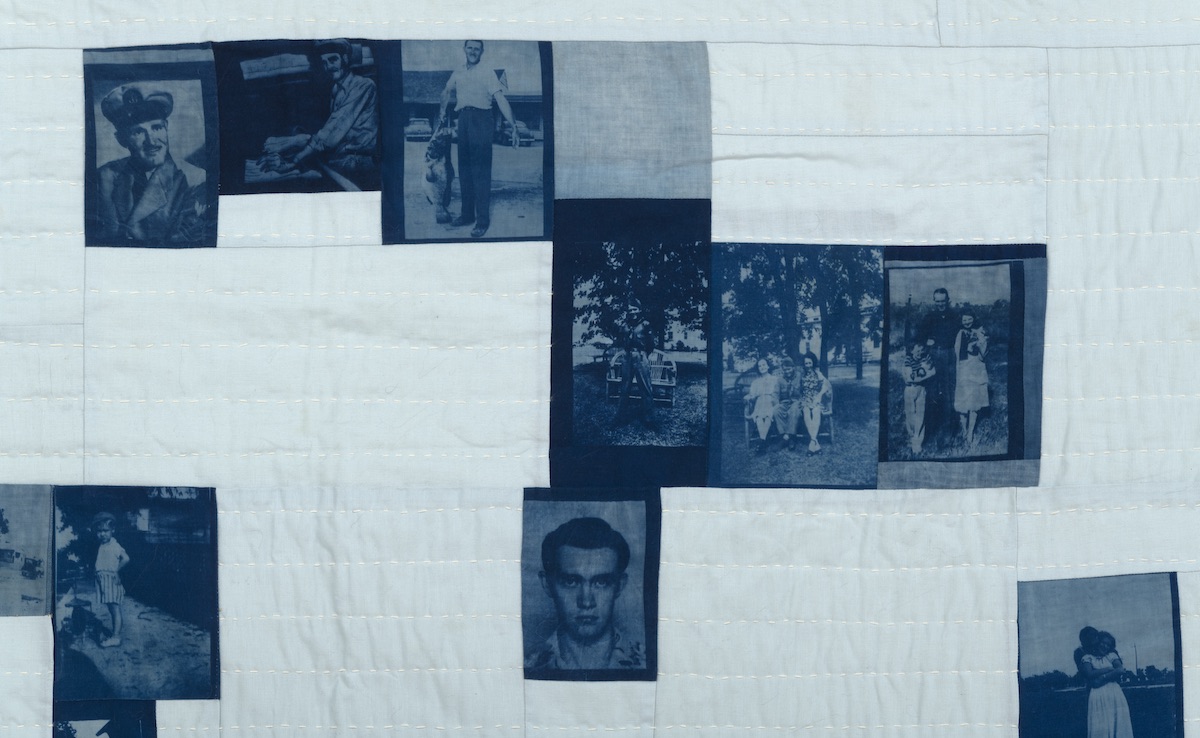

Johnpaul struggled with schizophrenia most of his adult life. His illness had a seasonal component, flaring up in the hot August weather of their Houston home, running in cycles of disappearance, arrest, institutionalization, and jail. Two years prior to his disappearance, in May of 2017, Crabb began working on a quilt about her brother, which came out of a deep need to give her swirling emotions a place to live outside of her own body. The result, entitled “Dear You,” is masterful. Delicate hand-appliquéd symbols adorn the quilt top and intentional stitching traces these objects of memory. All of the fabric was naturally dyed, a finicky process even with the most practiced hand, but fabulously expressed by hers.

Crabb doesn’t have the traditional story of learning these craft skills from her mother or grandmother—she didn’t have much of an artistic upbringing at all. It wasn’t until she was twenty and her father had passed away that she even considered college, mostly as a way to help her get out of Houston. “My father’s death was devastating for so long,” she says, “but it also gave me the opportunity to change my trajectory.”

Working at a photo lab after losing her father, Crabb reconnected with a high school art teacher who convinced her to give college a chance. She was accepted to MICA and moved to Baltimore to study photography, but she hoped to also experiment with other media. When the Fiber Department purchased a digital printer, she jumped at the opportunity to use it for one project but otherwise didn’t find ways to cross disciplines.

While still at MICA, she began working at Current Space, an arts collective and gallery in Baltimore’s Bromo Arts District. After graduation, taking on an administrative role allowed her to stay involved in the art community although she wasn’t making much art. Crabb left Current in 2014 when she gave birth to her daughter, and she worried that her connection to the arts would disappear. Instead, she experienced a rebirth, finding time to fall back in love with art making.

Before her pregnancy, Crabb had begun to conceive of a new type of art practice. She found a quilter on Pinterest, Maura Ambrose of Folk Fibers, who was working in a contemporary style that inspired Crabb to give it a try. She borrowed a sewing machine and pieced together a baby quilt on her dining room table with no prior sewing experience and no instruction, just videos and pictures that she found on Instagram. She finished the quilt and gave it to a friend, but then promptly returned the machine, finding the process to be much harder than it looked.